<Back to Index>

- Physicist Joseph Henry, 1797

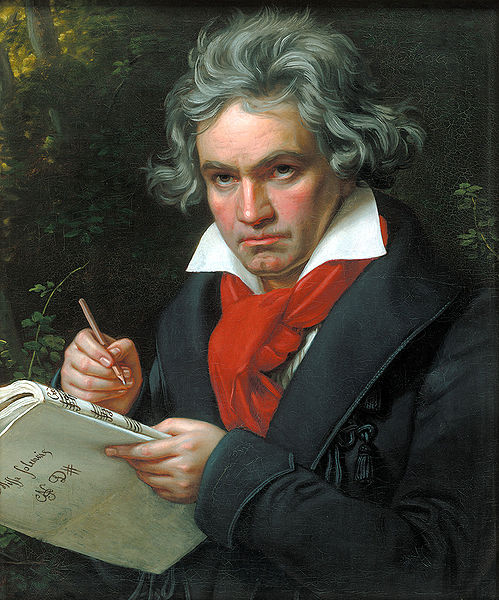

- Composer Ludwig van Beethoven, 1770

- Prime Minister of Canada William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1874

PAGE SPONSOR

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 1770 – 26 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He was the most crucial figure in the transitional period between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western classical music, and remains one of the most famous and influential composers of all time.

Born in Bonn, which was then capital of the Electorate of Cologne and a part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in present-day Germany, he moved to Vienna in his early twenties and settled there, studying with Joseph Haydn and quickly gaining a reputation as a virtuoso pianist. His hearing began to deteriorate in the late 1790s, yet he continued to compose, conduct, and perform, even after becoming completely deaf.

Beethoven was the grandson of a musician of Flemish origin named Lodewijk van Beethoven (1712 – 1773). Beethoven was named after his grandfather, as Lodewijk is the Dutch counterpart of Ludwig. Beethoven's grandfather was employed as a bass singer at the court of the Elector of Cologne, rising to become Kapellmeister (music director). He had one son, Johann van Beethoven (1740 – 1792),

who worked as a tenor in the same musical establishment, also giving

lessons on piano and violin to supplement his income. Johann

married Maria Magdalena Keverich in 1767; she was the daughter of

Johann Heinrich Keverich, who had been the head chef at the court of the Archbishopric of Trier. Beethoven was born of this marriage in Bonn; he was baptized in a Roman Catholic service on 17 December 1770, and was probably born the previous day, 16 December. Children of that era were usually baptized the day after birth; and it is known that Beethoven's family and his teacher Johann Albrechtsberger celebrated

his birthday on 16 December. While this evidence supports the case for

16 December 1770 as Beethoven's date of birth, it cannot be stated with

certainty, as there is no documentary evidence of it (only his

baptismal record survives). Of

the seven children born to Johann van Beethoven, only the second-born,

Ludwig, and two younger brothers survived infancy. Caspar Anton Carl

was born on 8 April 1774, and Nikolaus Johann, the youngest, was

born on 2 October 1776. Beethoven's

first music teacher was his father. A traditional belief concerning

Johann is that he was a harsh instructor, and that the child Beethoven,

"made to stand at the keyboard, was often in tears". However, the New Grove indicates

that there is no solid documentation to support it, and asserts that

"speculation and myth-making have both been productive." Beethoven

had other local teachers as well: the court organist Gilles van den

Eeden (d. 1782), Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer (a family friend, who taught

Beethoven piano), and a relative, Franz Rovantini (violin and viola). His musical talent manifested itself early. Johann, aware of Leopold Mozart's successes in this area, attempted to exploit his son as a child prodigy, claiming that Beethoven was six (he was seven) on the posters for Beethoven's first public performance in March 1778. Some time after 1779, Beethoven began his studies with his most important teacher in Bonn, Christian Gottlob Neefe, who was appointed the Court's Organist in that year. Neefe

taught Beethoven composition, and by March 1783 had helped him write

his first published composition: a set of keyboard variations (WoO 63). Beethoven

soon began working with Neefe as assistant organist, first on an unpaid

basis (1781), and then as paid employee (1784) of the court chapel

conducted by the Kapellmeister Andrea Luchesi. His first three piano sonatas, named "Kurfürst" ("Elector") for their dedication to the Elector Maximilian Frederick,

were published in 1783. Maximilian Frederick, who died in 1784, not

long after Beethoven's appointment as assistant organist, had noticed

Beethoven's talent early, and had subsidized and encouraged the young

Beethoven's musical studies. Maximilian Frederick's successor as the Elector of Bonn was Maximilian Franz, the youngest son of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, and he brought notable changes to Bonn. Echoing changes made in Vienna by his brother Joseph, he introduced reforms based on Enlightenment philosophy,

with increased support for education and the arts. The teenage

Beethoven was almost certainly influenced by these changes. He may also

have been strongly influenced at this time by ideas prominent in freemasonry, as Neefe and others around Beethoven were members of the local chapter of the Order of the Illuminati. In

March 1787 Beethoven traveled to Vienna (it is unknown at whose

expense) for the first time, apparently in the hope of studying with Mozart. The details of their relationship are uncertain, including whether or not they actually met. After

just two weeks there Beethoven learned that his mother was severely

ill, and he was forced to return home. His mother died shortly

thereafter, and the father lapsed deeper into alcoholism. As a result,

Beethoven became responsible for the care of his two younger brothers,

and he spent the next five years in Bonn. Beethoven

was introduced to a number of people who became important in his life

in these years. Franz Wegeler, a young medical student, introduced him

to the von Breuning family (one of whose daughters Wegeler eventually

married). Beethoven was often at the von Breuning household, where he

was exposed to German and classical literature, and where he also gave

piano instruction to some of the children. The von Breuning family

environment was also less stressful than his own, which was

increasingly dominated by his father's strict control and descent into

alcoholism. It is also in these years that Beethoven came to the attention of Count Ferdinand von Waldstein, who became a lifelong friend and financial supporter.

In 1789, he obtained a legal order by which half of his father's salary was paid directly to him for support of the family. He also contributed further to the family's income by playing viola in the court orchestra. This familiarized Beethoven with a variety of operas, including three of Mozart's operas performed at court in this period. He also befriended Anton Reicha, a flautist and violinist of about his own age who was the conductor's nephew. With the Elector's help, Beethoven moved to Vienna in 1792. He was probably first introduced to Joseph Haydn in late 1790, when the latter was traveling to London and stopped in Bonn around Christmas time. They

definitely met in Bonn on Haydn's return trip from London to Vienna in

July 1792, and it is likely that arrangements were made at that time

for Beethoven to study with the old master. In

the intervening years, Beethoven composed a significant number of works

(none were published at the time, and most are now listed as works without opus) that demonstrated a growing range and maturity of style. Musicologists have identified a theme similar to those of his third symphony in a set of variations written in 1791. Beethoven left Bonn for Vienna in November 1792, amid rumors of war spilling out of France, and learned shortly after his arrival that his father had died. Count

Waldstein in his farewell note to Beethoven wrote: "Through

uninterrupted diligence you will receive Mozart's spirit through

Haydn's hands." Beethoven

responded to the widespread feeling that he was a successor to the

recently deceased Mozart over the next few years by studying that

master's work and writing works with a distinctly Mozartean flavor. Beethoven

did not immediately set out to establish himself as a composer, but

rather devoted himself to study and to playing the piano. Working under

Haydn's direction, he sought to master counterpoint. He also took violin lessons from Ignaz Schuppanzigh. Early in this period, he also began receiving occasional instruction from Antonio Salieri, primarily in Italian vocal composition style; this relationship persisted until at least 1802, and possibly 1809. With

Haydn's departure for England in 1794, Beethoven was expected by the

Elector to return home. He chose instead to remain in Vienna,

continuing his instruction in counterpoint with Johann Albrechtsberger and

other teachers. Although his stipend from the Elector expired, a number

of Viennese noblemen had already recognized his ability and offered him

financial support, among them Prince Joseph Franz Lobkowitz, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, and Baron Gottfried van Swieten.

By

1793, Beethoven established a reputation in Vienna as a piano virtuoso

and improviser in the salons of the nobility, often playing the preludes and fugues of J.S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier. His friend Nikolaus Simrock had also begun publishing his compositions; the first are believed to be a set of variations (WoO 66). Beethoven

spent much of 1794 composing, and apparently withheld works from

publication so that their publication in 1795 would have greater impact. Beethoven's first public performance in Vienna was in March 1795, a concert in which he debuted a piano concerto. It is uncertain whether this was the First or Second,

as documentary evidence is unclear, and both concertos were in a

similar state of near-completion (neither was completed or published

for several years). Shortly after this performance, he arranged for the publication of the first of his compositions to which he assigned an opus number, the piano trios of Opus 1. These works were dedicated to his patron Prince Lichnowsky, and were a financial success; Beethoven's profits were nearly sufficient to cover his living expenses for a year. In 1796, Beethoven embarked on a tour of central European cultural centers that was an echo of a similar tour by Mozart in 1789. Accompanied by Prince Lichnowsky (who also accompanied Mozart on his tour), Beethoven visited Prague, Dresden, Leipzig,

and Berlin, composing and performing to acclaim. He spent the most time

in Prague, where his reputation had already preceded him through Lichnowsky's family connections, and Berlin, where he composed two cello sonatas (Op. 5) dedicated to King Friedrich Wilhelm II,

a lover of music who played that instrument. These works are notable

for successfully combining virtuoso cello and piano parts, a difficult

task considering the differing natures of the two instruments. The

king presented Beethoven with a snuffbox full of gold coins; Beethoven

observed that the trip earned him "a good deal of money". Beethoven

returned to Vienna in July 1796, and embarked on another tour in

November, heading east instead of north, to the cities of Pressburg

(present-day Bratislava) and Pest. At Pressburg he performed on a piano sent from Vienna by his friend Andreas Streicher, a piano he joked was "far too good for me..because it robs me of the freedom to produce my own tone". Beethoven

spent most of 1797 in Vienna, where he continued to compose (apparently

in response to an increasing number of commissions) and perform,

although he was apparently stricken with a serious disease (possibly typhus)

in the summer or autumn. It is also around this time (although it may

have been as early as 1795) that he first became aware of issues with

his hearing. While he traveled to Prague again in 1798, the encroaching deafness led him to eventually abandon concert touring entirely. Between 1798 and 1802 Beethoven finally tackled what he considered the pinnacles of composition: the string quartet and the symphony. With the composition of his first six string quartets (Op. 18) between

1798 and 1800 (written on commission for, and dedicated to, Prince

Lobkowitz), and their publication in 1801, along with premieres of the First and Second Symphonies

in 1800 and 1802, Beethoven was justifiably considered one of the most

important of a generation of young composers following after Haydn and

Mozart. He continued to write in other forms, turning out widely known piano sonatas like the "Pathétique"

sonata (Op. 13), which Cooper describes as "surpass[ing] any of his

previous compositions, in strength of character, depth of emotion,

level of originality, and ingenuity of motivic and tonal manipulation". He also completed his Septet (Op. 20) in 1799, which was one of his most popular works during his lifetime. For the premiere of his First Symphony,

Beethoven hired the Burgtheater on 2 April 1800, and staged an

extensive program of music, including works by Haydn and Mozart, as

well as the Septet, the First Symphony, and one of his piano concertos

(the latter three works all then unpublished). The concert, which the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung described

as "the most interesting concert in a long time", was not without

difficulties; among other criticisms was that "the players did not

bother to pay any attention to the soloist". While Mozart and Haydn were undeniable influences (for example, Beethoven's quintet for piano and winds is said to bear a strong resemblance to Mozart's work for the same configuration, albeit with his own distinctive touches), other composers like Muzio Clementi were also stylistic influences.

Beethoven's melodies, musical development, use of modulation and

texture, and characterization of emotion all set him apart from his

influences, and heightened the impact some of his early works made when

they were first published. By the end of 1800 Beethoven and his music were already much in demand from patrons and publishers. In May of 1799, Beethoven gave piano lessons to the daughters of Hungarian Countess Anna Brunsvik.

While this round of lessons lasted less than one month, Beethoven

formed a relationship with the older daughter Josephine that has been

the subject of much speculation ever since. Shortly after these lessons

she married Count Josef Deym, and Beethoven was a regular visitor at

their house, giving lessons and playing at parties. While her marriage

was by all accounts unhappy, the couple had four children, and her

relationship with Beethoven did not intensify until after Deym died in

1804. Beethoven had few other students. From 1801 to 1805, he tutored Ferdinand Ries, who went on to become a composer and later wrote Beethoven remembered, a book about their encounters. The young Carl Czerny studied with Beethoven from 1801 to 1803. Czerny went on to become a renowned music teacher himself, taking on Franz Liszt as one of his students, and also gave the Vienna premiere of Beethoven's fifth piano concerto (the "Emperor") in 1812. Beethoven's

compositions between 1800 and 1802 were dominated by two works,

although he continued to produce smaller works, including the Moonlight Sonata. In the spring of 1801 he completed The Creatures of Prometheus, a ballet.

The work was such a success that it received numerous performances in

1801 and 1802, and Beethoven rushed to publish a piano arrangement to

capitalize on its early popularity. In the spring of 1802 he completed the Second Symphony,

intended for performance at a concert that was eventually cancelled.

The symphony received its premiere at a subscription concert in April

1803 at the Theater an der Wien,

where Beethoven had been appointed as composer in residence. In

addition to the Second Symphony, the concert also featured the First

Symphony, the Third Piano Concerto, and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives.

While reviews were mixed, the concert was a financial success;

Beethoven was able to charge three times the cost of a typical concert

ticket. Beethoven's

business dealings with publishers also began to improve in 1802 when

his brother Carl, who had previously assisted him more casually, began

to assume a larger role in the management of his affairs. In addition

to negotiating higher prices for recently composed works, Carl also

began selling some of Beethoven's earlier unpublished works, and

encouraged Beethoven (against the latter's preference) to also make

arrangements and transcriptions of his more popular works for other

instrument combinations. Beethoven acceded to these requests, as he

could not prevent publishers from hiring others to do similar

arrangements of his works. Around 1796, Beethoven began to lose his hearing. He suffered a severe form of tinnitus,

a "ringing" in his ears that made it hard for him to perceive and

appreciate music; he also avoided conversation. The cause of

Beethoven's deafness is unknown, but it has variously been attributed to syphilis, lead poisoning, typhus, auto-immune disorder (such as systemic lupus erythematosus),

and even his habit of immersing his head in cold water to stay awake.

The explanation, from the autopsy of the time, is that he had a

"distended inner ear" which developed lesions over time. Because of the

high levels of lead found in samples of Beethoven's hair, that

hypothesis has been extensively analyzed. While the likelihood of lead

poisoning is very high, the deafness associated with it seldom takes

the form that Beethoven exhibited. As

early as 1801, Beethoven wrote to friends describing his symptoms and

the difficulties they caused in both professional and social settings

(although it is likely some of his close friends were already aware of

the problems). Beethoven, on the advice of his doctor, lived in the small Austrian town of Heiligenstadt, just outside Vienna, from April to October 1802 in an attempt to come to terms with his condition. There he wrote his Heiligenstadt Testament, which records his resolution to continue living for and through his art. Over time, his hearing loss became profound: there is a well-attested story that, at the end of the premiere of his Ninth Symphony, he had to be turned around to see the tumultuous applause of the audience; hearing nothing, he wept. Beethoven's hearing loss did not prevent his composing music, but it made playing

at concerts — a lucrative source of income — increasingly difficult. After

a failed attempt in 1811 to perform his own Piano Concerto No. 5 (the "Emperor"), he never performed in public again. A

large collection of Beethoven's hearing aids such as special ear horns

can be viewed at the Beethoven House Museum in Bonn, Germany. Despite

his obvious distress, Carl Czerny remarked that Beethoven could still

hear speech and music normally until 1812. By

1814 however, Beethoven was almost totally deaf, and when a group of

visitors saw him play a loud arpeggio of thundering bass notes at his

piano remarking, "Ist es nicht schön?" (Is it not beautiful?),

they felt deep sympathy considering his courage and sense of humor. As

a result of Beethoven's hearing loss, a unique historical record has

been preserved: his conversation books. Used primarily in the last ten

or so years of his life, his friends wrote in these books so that he

could know what they were saying, and he then responded either orally

or in the book. The books contain discussions about music and other

issues, and give insights into his thinking; they are a source for

investigation into how he felt his music should be performed, and also

his perception of his relationship to art. Unfortunately, 264 out of a

total of 400 conversation books were destroyed (and others were

altered) after Beethoven's death by Anton Schindler, in his attempt to paint an idealized picture of the composer. While

Beethoven earned income from publication of his works and from public

performances, he also depended on the generosity of patrons for income,

for whom he gave private performances and copies of works they

commissioned for an exclusive period prior to their publication. Some

of his early patrons, including Prince Lobkowitz and Prince Lichnowsky,

gave him annual stipends in addition to commissioning works and

purchasing published works. Perhaps Beethoven's most important aristocratic patron was Archduke Rudolph, the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II, who in 1803 or 1804 began to study piano and composition with Beethoven. The cleric (Cardinal-Priest) and the composer became friends, and their meetings continued until

1824. Beethoven dedicated 14 compositions to Rudolph, including the Archduke Trio (1811) and his great Missa Solemnis (1823).

Rudolph, in turn, dedicated one of his own compositions to Beethoven.

The letters Beethoven wrote to Rudolph are today kept at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna. In the fall of 1808, after having been rejected for a position at the royal theatre, Beethoven received an offer from Napoleon's brother Jérôme Bonaparte, then king of Westphalia, for a well-paid position as Kapellmeister at the court in Cassel.

To persuade him to stay in Vienna, the Archduke Rudolph, Count Kinsky

and Prince Lobkowitz, after receiving representations from the

composer's friends, pledged to pay Beethoven a pension of 4000 florins

a year. Only Archduke Rudolph paid his share of the pension on the

agreed date. Kinsky, immediately called to duty as an officer, did not

contribute and soon died after falling from his horse. Lobkowitz

stopped paying in September 1811. No successors came forward to

continue the patronage, and Beethoven relied mostly on selling

composition rights and a small pension after 1815. The effects of these

financial arrangements were undermined to some extent by war with France, which caused significant inflation when the government printed money to fund its war efforts. Beethoven's

return to Vienna from Heiligenstadt was marked by a change in musical

style, now recognized as the start of his "Middle" or "Heroic" period.

According to Carl Czerny, Beethoven said, "I am not satisfied with the

work I have done so far. From now on I intend to take a new way". The first major work of this new way was the Third Symphony in

E flat, known as the "Eroica". While other composers had written

symphonies with implied programs, or stories, this work was longer and

larger in scope than any previously written symphony. When it premiered

in early 1805 it received a mixed reception, with some listeners

objecting to its length or failing to understand its structure, while

others viewed it as another masterpiece. Beethoven

composed highly ambitious works throughout the Middle period, often

heroic in tone, that extended the scope of the classical musical

language Beethoven had inherited from Haydn and Mozart. The Middle

period work includes the Third through Eighth Symphonies, the string quartets 7–11, the "Waldstein" and "Appassionata" piano sonatas, Christ on the Mount of Olives, the opera Fidelio, the Violin Concerto and

many other compositions. During this time Beethoven earned his living

from the sale and performance of his work, and from the continuing

support of wealthy patrons. His position at the Theater and der Wien

was terminated when the theater changed management in early 1804, and

he was forced to move temporarily to the suburbs of Vienna with his

friend Stephan von Breuning. This slowed work on Fidelio, his largest work to date, for a time. It was delayed again by the Austrian censor, and finally premiered in November 1805 to houses that were nearly empty because of French occupation of the city. In addition to being a financial failure, this version of Fidelio was also a critical failure, and Beethoven began revising it.

The work of the Middle period established Beethoven's reputation as a great composer. In a review from 1810, he was enshrined by E.T.A. Hoffman as one of the three great "Romantic" composers; Hoffman called Beethoven's Fifth Symphony "one

of the most important works of the age". A particular trauma for

Beethoven occurred during this period in May 1809, when the attacking

forces of Napoleon bombarded Vienna.

According to Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven, very worried that the noise

would destroy what remained of his hearing, hid in the basement of his

brother's house, covering his ears with pillows. He was composing the "Emperor" Concerto at the time. Beethoven was introduced to Giulietta Guicciardi in about 1800 through the Brunsvik family.

His mutual love relationship with Guicciardi is mentioned in a November

1801 letter to his boyhood friend, Franz Wegeler. Beethoven dedicated

to Giulietta his Sonata No. 14, popularly known as the "Moonlight" Sonata.

Marriage plans were thwarted by Giulietta's father and perhaps

Beethoven's common lineage. In 1803 she married Count Wenzel Robert von

Gallenberg (1783 – 1839), himself an amateur composer. Beethoven's

relationship with Josephine Deym notably deepened after the death of

her first husband in 1804. There is some evidence that Beethoven may

have proposed to her, at least informally. While the relationship was

apparently reciprocated, she, with some regret, turned him down, and

their relationship effectively ended in 1807. She cited her "duty", an

apparent reference to the fact that she was born of nobility and he was

a commoner. It is also likely that he considered proposing (whether he actually did or not is unknown) to Therese Malfatti, the dedicatee of "Für Elise" in 1810; his common status may also have interfered with those plans. In

the spring of 1811 Beethoven became seriously ill, suffering headaches

and bad fevers. On the advice of his doctor, he spent six weeks in the Bohemian spa town of Teplitz.

The following winter, which was dominated by work on the Seventh

symphony, he was again ill, and decided to spend the summer of 1812 at

Teplitz. It is likely that he was at Teplitz when he wrote three love

letters to an "Immortal Beloved". While

the identity of the intended recipient is an ongoing subject of debate,

the most likely candidate, according to what is known about people's

movements and the contents of the letters, is Antonie Brentano, a married woman with whom he had begun a friendship in 1810. Beethoven traveled to Karlsbad in

late July, where he stayed in the same guesthouse as the Brentanos.

After traveling with them for a time, he returned to Teplitz, where

after another bout of gastric illness, he left for Linz to visit his brother Johann. Beethoven's

visit to his brother was made in an attempt to end the latter's immoral

cohabitation with Therese Obermayer, a woman who already had an

illegitimate child. He was unable to convince Johann to end the

relationship, so he appealed to the local civic and religious

authorities. The end result of Beethoven's meddling was that Johann and

Therese married on 9 November. In

early 1813 Beethoven apparently went through a difficult emotional

period, and his compositional output dropped for a time. Historians

have suggested a variety of causes, including his lack of success at

romance. His personal appearance, which had generally been neat,

degraded, as did his manners in public, especially when dining. Some of

his (married) desired romantic partners had children (leading to

assertions among historians of Beethoven's possible paternity), and his

brother Carl was seriously ill. Beethoven took care of his brother and

his family, an expense that he claimed left him penniless. He was

unable to obtain a date for a concert in the spring of 1813, which, if

successful, would have provided him with significant funds. Beethoven was finally motivated to begin significant composition again in June 1813, when news arrived of the defeat of one of Napoleon's armies at Vitoria, Spain, by a coalition of forces under the Duke of Wellington. This news stimulated him to write the battle symphony known as Wellington's Victory.

It was premiered on 8 December at a charity concert for victims of the

war along with his Seventh Symphony. The work was a popular hit, likely

because of its programmatic style which was entertaining and easy to

understand. It received repeat performances at concerts Beethoven

staged in January and February 1814. Beethoven's renewed popularity led

to demands for a revival of Fidelio,

which, in its third revised version, was also well-received when it

opened in July. That summer he also composed a piano sonata for the

first time in five years (No. 27, Opus 90). This work was in a markedly more Romantic style

than his earlier sonatas. He was also one of many composers who

produced music in a patriotic vein to entertain the many heads of state

and diplomats that came to the Congress of Vienna that began in November 1814. His output of songs included his only song cycle, "An die ferne Geliebte", and the extraordinarily expressive, but almost incoherent, "An die Hoffnung" (Opus 94). Between

1815 and 1817 Beethoven's output dropped again. Part of this Beethoven

attributed to a lengthy illness (he called it an "inflammatory fever")

that afflicted him for more than a year, starting in October 1816. Biographers

have speculated on a variety of other reasons that also contributed to

the decline in creative output, including the difficulties in the

personal lives of his would-be paramours and the harsh censorship

policies of the Austrian government. The illness and death of his

brother Carl from consumption likely also played a role. Carl

had been ill for some time, and Beethoven spent a small fortune in 1815

on his care. When he finally died on 15 November 1815, Beethoven

immediately became embroiled in a protracted legal dispute with Carl's

wife Johanna over custody of their son Karl, then nine years old.

Beethoven, who considered Johanna an unfit parent because of her morals

(she had an illegitimate child by a different father before marrying

Carl, and had been convicted of theft) and financial management, had

successfully applied to Carl to have himself named sole guardian of the

boy; but a late codicil to

Carl's will gave him and Johanna joint guardianship. While Beethoven

was successful at having his nephew removed from her custody in

February 1816, the case was not fully resolved until 1820, and he was

frequently preoccupied by the demands of the litigation and seeing to

the welfare of the boy, whom he first placed in a private school. The

custody fight brought out the very worst aspects of Beethoven's

character; in the lengthy court cases Beethoven stopped at nothing to

ensure that he achieved this goal, and even stopped composing for long

periods. The Austrian court system had one court for the nobility,

The R&I Landrechte, and another for commoners, The Civil Court of

the Magistrate. Beethoven disguised the fact that the Dutch "van" in

his name did not denote nobility as does the German "von", and

his case was tried in the Landrechte. Owing to his influence with the

court, Beethoven felt assured of a favorable outcome. Beethoven was

awarded sole guardianship. While giving evidence to the Landrechte,

however, Beethoven inadvertently admitted

that he was not nobly born. The case was transferred to the Magistracy

on 18 December 1818, where he lost sole guardianship. Beethoven

appealed, and regained custody of Karl. Johanna's appeal for justice to

the Emperor was not successful: the Emperor "washed his hands of the

matter". Beethoven stopped at nothing to blacken her name, as can be

read in surviving court papers. During the years of custody that

followed, Beethoven attempted to ensure that Karl lived to the highest

of moral standards. His overbearing manner and frequent interference in

his nephew's life, especially as he grew into a young man, apparently

drove Karl to attempt suicide on 31 July 1826 by shooting himself in

the head. He survived, and was brought to his mother's house, where he

recuperated. He and Beethoven reconciled, but Karl was insistent on

joining the army, and last saw Beethoven in early 1827. The only major works Beethoven produced during this time were two cello sonatas, a piano sonata, and collections of folk song settings. He began sketches for the Ninth Symphony in 1817. Beethoven began a renewed study of older music, including works by J.S. Bach and Handel, that were then being published in the first attempts at complete editions. He composed the Consecration of the House Overture,

which was the first work to attempt to incorporate his new influences.

But it is when he returned to the keyboard to compose his first new

piano sonatas in almost a decade, that a new style, now called his

"late period", emerged. The works of the late period are commonly held

to include the last five piano sonatas and the Diabelli Variations, the last two sonatas for cello and piano, the late quartets, and two works for very large forces: the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony. By

early 1818 Beethoven's health had improved, and his nephew had moved in

with him in January. On the downside, his hearing had deteriorated to

the point that conversation became difficult, necessitating the use of

conversation books. His household management had also improved

somewhat; Nanette Streicher, who had assisted in his care during his

illness, continued to provide some support, and he finally found a

decent cook. His musical output in 1818 was still somewhat reduced, with song collections and the Hammerklavier Sonata his

only notable compositions, although he continued to work on sketches

for two symphonies (that eventually coalesced into the enormous Ninth

Symphony). In 1819 he was again preoccupied by the legal processes

around Karl, and began work on the Diabelli Variations and the Missa Solemnis. For

the next few years he continued to work on the Missa, composing piano

sonatas and bagatelles to satisfy the demands of publishers and the

need for income, and completing the Diabelli Variations. He was ill

again for an extended time in 1821, and completed the Missa in 1823,

three years after its original due date. He also opened discussions

with his publishers over the possibility of producing a complete

edition of his works, an idea that was arguably not fully realized

until 1971. Beethoven's brother Johann began to take a hand in his

business affairs around this time, much in the way Carl had earlier,

locating older unpublished works to offer for publication and offering

the Missa to multiple publishers with the goal of getting a higher

price for it. Two commissions in 1822 improved Beethoven's financial prospects. The Philharmonic Society of London offered a commission for a symphony, and Prince Nikolay Golitsin of St. Petersburg offered

to pay Beethoven's price for three string quartets. The first of these

spurred Beethoven to finish the Ninth Symphony, which was premiered,

along with the Missa Solemnis, on 7 May 1824, to great acclaim at the Kärntnertortheater. The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung gushed

"inexhaustible genius had shown us a new world", and Carl Czerny wrote

that his symphony "breathes such a fresh, lively, indeed youthful

spirit [...] so much power, innovation, and beauty as ever [came] from

the head of this original man, although he certainly sometimes led the

old wigs to shake their heads." Unlike his earlier concerts, Beethoven made little money on this one, as the expenses of mounting it were significantly higher. A

second concert on 24 May, in which the producer guaranteed Beethoven a

minimum fee, was poorly attended; nephew Karl noted that "many people

have already gone into the country". It was Beethoven's last public concert. Beethoven then turned to writing the string quartets for Golitsin. This series of quartets,

known as the "Late Quartets", went far beyond what either musicians or

audiences were ready for at that time. One musician commented that "we

know there is something there, but we do not know what it is." Composer Louis Spohr called

them "indecipherable, uncorrected horrors", though that opinion has

changed considerably from the time of their first bewildered reception.

They continued (and continue) to inspire musicians and composers, from Richard Wagner to Béla Bartók, for their unique forms and ideas. Of the late quartets, Beethoven's favorite was the Fourteenth Quartet, op. 131 in C# minor, upon hearing which Schubert is said to have remarked, "After this, what is left for us to write?" Beethoven

wrote the last quartets amidst failing health. In April 1825 he was

bedridden, and remained ill for about a month. The illness — or more

precisely, his recovery from it — is remembered for having given rise to

the deeply felt slow movement of the Fifteenth Quartet, which Beethoven called "Holy song of thanks ('Heiliger dankgesang') to

the divinity, from one made well". He went on to complete the

(misnumbered) Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Sixteenth Quartets.

The last work completed by Beethoven was the substitute final movement

of the Thirteenth Quartet, deemed necessary to replace the difficult Große Fuge.

Shortly thereafter, in December 1826, illness struck again, with

episodes of vomiting and diarrhea that nearly ended his life. Beethoven

was bedridden for most of his remaining months, and many friends came

to visit. He died on 26 March 1827, during a thunderstorm. His friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner, who was present at the time, claimed that there was a peal of thunder at the moment of death. An autopsy revealed significant liver damage, which may have been due to heavy alcohol consumption. Unlike Mozart,

who was buried anonymously in a communal grave (such being the custom

at the time), 20,000 Viennese citizens lined the streets for

Beethoven's funeral on 29 March 1827. Franz Schubert,

who died the following year and was buried next to Beethoven, was one

of the torchbearers. After a Requiem Mass at the church of the Holy

Trinity (Dreifaltigkeitskirche), Beethoven was buried in the Währing cemetery, north-west of Vienna. His remains were exhumed for study in 1862, and moved in 1888 to Vienna's Zentralfriedhof. There is dispute about the cause of Beethoven's death; alcoholic cirrhosis, syphilis, infectious hepatitis, lead poisoning, sarcoidosis and Whipple's disease have all been proposed. Friends

and visitors before and after his death clipped locks of his hair, some

of which have been preserved and subjected to additional analysis, as

have skull fragments removed during the 1862 exhumation. Some of these analyses have led to controversial assertions that Beethoven was accidentally poisoned to death by excessive doses of lead-based treatments administered under instruction from his doctor. Beethoven's personal life was troubled by his encroaching deafness,

which led him to contemplate suicide (documented in his Heiligenstadt

Testament). Beethoven was often irascible and may have suffered from bipolar disorder and

irritability brought on by chronic abdominal pain (beginning in his

twenties) that has been attributed to possible lead poisoning. Nevertheless,

he had a close and devoted circle of friends all his life, thought to

have been attracted by his strength of personality. Toward the end of

his life, Beethoven's friends competed in their efforts to help him

cope with his incapacities. Sources

show Beethoven's disdain for authority, and for social rank. He stopped

performing at the piano if the audience chatted amongst themselves, or

afforded him less than their full attention. At soirées, he

refused to perform if suddenly called upon to do so. Eventually, after

many confrontations, the Archduke Rudolph decreed that the usual rules

of court etiquette did not apply to Beethoven. Beethoven was attracted to the ideals of the Enlightenment.

In 1804, when Napoleon's imperial ambitions became clear, Beethoven

took hold of the title-page of his Third Symphony and scratched the

name Bonaparte out so violently that he made a hole in the paper. He

later changed the work's title to "Sinfonia Eroica, composta per

festeggiare il sovvenire d'un grand'uom" ("Heroic Symphony, composed to

celebrate the memory of a great man"), and he rededicated it to his

patron, Prince Joseph Franz von Lobkowitz, at whose palace it was first

performed. The fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony features an elaborate choral setting of Schiller's Ode An die Freude ("Ode to Joy"), an optimistic hymn championing the brotherhood of humanity.