<Back to Index>

- Physicist Joseph Henry, 1797

- Composer Ludwig van Beethoven, 1770

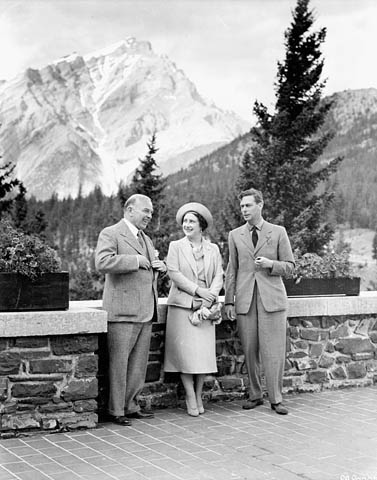

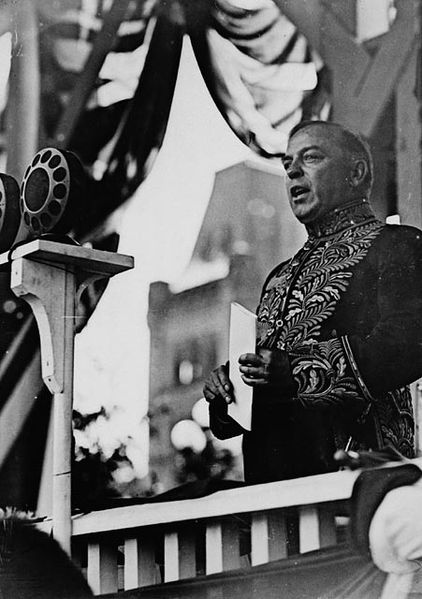

- Prime Minister of Canada William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1874

PAGE SPONSOR

William Lyon Mackenzie King, PC, OM, CMG (17 December 1874 – 22 July 1950) was the dominant Canadian political leader from the 1920s to the 1940s. He served as the tenth Prime Minister of Canada from 29 December 1921 to 28 June 1926; 25 September 1926 to 6 August 1930; and 23 October 1935 to 15 November 1948. A Liberal with 21 years in office, he was the longest-serving Prime Minister in British Commonwealth history. He is commonly known either by his full name or as Mackenzie King. Trained in law and social work he was keenly interested in the human condition; as a boy his motto was "Help those that cannot help themselves". He had a quick temper, but he was kindhearted and dreamed of shaping Canada for the better.

King was born in Berlin, Ontario (now known as Kitchener) to John King and Isabella Grace Mackenzie. His maternal grandfather was William Lyon Mackenzie, first mayor of Toronto and leader of the Upper Canada Rebellion in 1837. His father was a lawyer, later a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School. King had three siblings. He attended Berlin Central School (now Suddaby Public School) and Berlin High School (now Kitchener-Waterloo Collegiate and Vocational School). Tutors were hired to teach him more politics, science, math, English and French. The father was a lawyer with a struggling practice in a small city, and never enjoyed financial security; his parents lived a life of shabby gentility, employing servants and tutors they could scarcely afford. The son became a life-long practising Presbyterian with a dedication to applying Christian virtues to social issues in the style of the Social Gospel. He never favoured socialism.

King earned five university degrees. He obtained two degrees from the University of Toronto: B.A. 1895, and M.A. 1897; he earned his LLB law degree in 1896 from Osgoode Hall, which at that time was independent of the University of Toronto. While studying in Toronto he met a wide circle of friends, many of whom became prominent. He was an early member and officer of The Kappa Alpha Society, which included a number of these individuals (two future Ontario Supreme Court Justices and the future Chairman of the University itself) and served as a location for the debate of political ideas. He also met Arthur Meighen, a future political rival; the two men did not get on especially well from the start. He was especially concerned with issues of social welfare and was influenced by the settlement house movement pioneered by Toynbee Hall in London. He played a central role in fomenting a students' strike at the university in 1895. He was in close touch, behind the scenes, with Vice-Chancellor William Mulock, for whom the strike provided a chance to embarrass his rivals Chancellor Blake and President Loudon. King failed to gain his immediate objective, a teaching position at the University, but earned political credit with the man who would invite him to Ottawa and make him a deputy minister only five years later.

After studying at the University of Chicago and working with Jane Addams at her settlement house, Hull House, Mackenzie King proceeded to Harvard University. He earned an M.A. in political economy in 1898. In 1909 Harvard granted him a PhD for a dissertation based on his study of "Oriental Immigration to Canada." In

1900 Mackenzie King became a civil servant in Ottawa assigned to study

labour issues. His reports covered a wide range of topics; a special

concern was Japanese immigration to Canada. In 1909, he became Canada's

first Deputy Minister of Labour, a civil service position. In 1901, King's roommate and best friend, Henry Albert Harper, died heroically during a skating party when a young woman fell through the ice of the partly frozen Ottawa River.

Harper dove into the water to save her, and perished in the attempt.

King led the effort to raise a memorial to Harper, which resulted in

the erection of the Sir Galahad statue on Parliament Hill in 1905. In 1906, King published a memoir of Harper, entitled The Secret of Heroism. He was first elected to Parliament as a Liberal in a 1908 by-election, and was re-elected by acclamation in a 1909 by-election following his appointment as the first-ever Minister of Labour.

King's

term as Minister of Labour was marked by two significant achievements.

He led the passage of the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act and the

Combines Investigation Act, which he had erected during his civil and

parliamentary service. The legislation significantly improved the

financial situation for millions of Canadian workers. He lost his seat in the 1911 general election, which saw the Conservatives defeat his Liberals. After his defeat Mackenzie King went on the lecture circuit on behalf of the Liberal Party. In June 1914 John D. Rockefeller, Jr. hired him as a senior staff member of the Rockefeller Foundation in

New York City, heading their new Department of Industrial Research. It

paid $12,000, compared to the meager $2500 a year the Liberal Party was

paying. He

worked for the Foundation until 1918, forming a close working

association and friendship with Rockefeller, advising him through the

turbulent period of the 1914 strike and Ludlow massacre at a family-owned coal company in Colorado, which subsequently set the stage for a new era in labor management in America. King

was not a pacifist, but he showed little enthusiasm for the Great War;

he faced criticism for not serving in Canada's military and instead

working for the Rockefellers. But he was 40 years old when the war

began, and was not in good physical condition. He never gave up his

Ottawa home, and travelled to the United States on an as-needed basis,

performing valuable service by helping to keep war-related industries

running smoothly. In 1917 Canada was in crisis; Mackenzie King supported Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier in

his opposition to conscription, which was violently opposed in Quebec.

The Liberal party became deeply split, with most Anglophones joining in

the pro-conscription Union government, a coalition controlled by the

Conservatives under Prime Minister Robert Borden. He returned to Canada to run in the 1917 election, which focused almost entirely on the conscription issue.

Unable to overcome a landslide against him, Mackenzie King lost in the

constituency of North York, which his grandfather had once represented.

He was Laurier's chosen successor as leader of the Liberal Party, but

it was deeply divided by Quebec's total opposition to conscription and

the agrarian revolt in Ontario and the Prairies. When Laurier died in

1919, Mackenzie King was elected leader thanks to the critical support

of the Quebec bloc, organized by his long-time lieutenant in Quebec, Ernest Lapointe (1876 – 1941).

Mackenzie King could not speak French and had minimal interest in

Quebec, but election after election (save for 1930) Lapointe produced

the critical seats to give the Liberals a majority in Commons. In the election of 1921 Liberals won a bare majority of seats; Mackenzie King became prime minister. Once

he became the Liberal leader in 1919 he paid attention to the Prairies.

With a highly romanticized view he envisioned the pioneers as morally

sound, hardworking individuals who lived close to nature and to God.

The reform ferment in the region meshed with his self-image as a social

reformer and fighter for the "people" against the "interests." Viewing

a glorious sunrise in Alberta in 1920, he wrote in his diary, "I

thought of the New Day, the New Social Order. It seems like Heaven's

prophecy of the dawn of a new era, revealed to me." Realism played a role too, since his party depended for its survival on the votes of Progressive party members

of parliament who represented farmers in Ontario and the Prairies. He

convinced many Progressives to return to the Liberal fold.

In the 1921 election, his party defeated Arthur Meighen and the Conservatives, and he became Prime Minister.

King's Liberals had only a minority position, however, since they won

115 out of 233 seats; the Conservatives won 50, the newly-formed Progressive Party won

65 (but declined to form the official Opposition), and there were three

Independents. This was the first minority government in Canadian

history. During

his first term of office, from 1921 to 1925, Mackenzie King pursued a

conservative domestic policy with the object of lowering wartime taxes

and, especially, wartime ethnic tensions, as well as defusing postwar

labour conflicts. "The War is over," he argued, "and for a long time to

come it is going to take all that the energies of man can do to bridge

the chasm and heal the wounds which the War has made in our social

life." He sought a Canadian voice independent of London in foreign affairs. In 1923 the British prime minister, David Lloyd George, appealed repeatedly to Mackenzie King for Canadian support in the Chanak crisis,

in which a war threatened between Britain and Turkey. He coldly replied

that the Canadian Parliament would decide what the policy to follow,

making clear it would not be bound by London's suggestions; the episode

led to the downfall of Lloyd George. Despite

prolonged negotiations, King was unable to attract the Progressives

into his government, but once Parliament opened, he relied on their

support to defeat non-confidence motions from the Conservatives. King

was also opposed in many policies by the Progressives, which did not

support trade tariffs. King faced a delicate balancing act of reducing

tariffs enough to please the prairie-based Progressives, who

represented farmers, but not too much to alienate his vital support in

industrial Ontario and Quebec. King and Meighen sparred constantly and

bitterly in Commons debates. As King's term wore on, the Progressives gradually weakened. Their effective and passionate leader, Thomas Crerar, resigned to return to his grain business, and was replaced by the more placid Robert Forke. The socialist reformer J.S. Woodsworth gradually

gained influence and power, and King was able to reach an accommodation

with him on policy matters, since the two shared many common ideas and

plans.

MacKenzie

King had a long-standing concern with city planning and the development

of the national capital. MacKenzie King had been trained in the

settlement house movement and included town planning and garden cities

as a component of his broader program of social reform. He drew on four

broad traditions in early North American planning: social planning, the

Parks Movement, the City Scientific, and the City Beautiful. King's

greatest impact was as the political champion for the planning and

development of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada's national capital, much of

which was completed in the two decades after his death. Confederation

Square in Ottawa, Ontario, was initially planned to be a civic plaza to

balance the nearby federal presence of Parliament Hill. A century of

federal planning, with the direct involvement of Prime Minister

Mackenzie King, repositioned it as a national space in the City

Beautiful style. The Great War monument was not installed until the

1939 royal visit, and Mackenzie King intended that the replanning of

the capital would be the World War II memorial. However, the symbolic

meaning of the World War II monument gradually expanded to become the

place of remembrance for all Canadian war sacrifices. King called an election in 1925, in which the Conservatives won the most seats, but not a majority in the House of Commons. King held on to power with the support of the Progressives.

Soon into his term, however, a bribery scandal in the Department of

Customs was revealed, which led to more support for the Conservatives

and Progressives, and the possibility that King would be forced to

resign. Mackenzie King advised the governor-general, Lord Byng, to dissolve Parliament and call another election, but Byng refused, the only time in Canadian history that the Governor General has exercised such a power. Instead Byng called upon the Conservative Party leader, Arthur Meighen,

to form a government. Meighen was unable to obtain a majority in the

Commons and he, too, advised dissolution, which this time was accepted.

In the ensuing election of 1926, Mackenzie King appealed for public

support of the constitutional principle that the governor-general must

accept the advice of his ministers, though this principle was at most

only customary. The Liberals argued that the governor-general had

interfered in politics and shown favor to one party over another.

Mackenzie King and his party won the election and a clear majority in

the Commons. The

crisis of 1926 provoked a consideration of the constitutional relations

between the self-governing dominions and the British government. During

the next five years the position of the governor-general of a dominion

was clarified; he ceased to be a representative of the British

government and became a personal representative of the British crown.

The independent position of the dominions in the Commonwealth and in

the international community was put on a firm legal foundation by the Statute of Westminster (1931). In

domestic affairs Mackenzie King strengthened the Liberal policy of

increasing the powers of the provincial governments by transferring to

the governments of Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan the ownership of

the crown lands within those provinces, as well as the subsoil rights.

In collaboration with the provincial governments he inaugurated a

system of old-age pensions based on need. In his third term, Mackenzie King introduced old-age pensions. In February 1930, he appointed Cairine Wilson as the first female senator in Canadian history. His government was in power during the beginning of the Great Depression,

but was slow to respond to the mounting crisis. Just prior to the

election, Mackenzie King blundered badly by carelessly responding to

criticism over his handling of the ecomomic crisis; he stated that he

"would not give a five-cent piece" to Tory provincial governments. This

turned into the key election issue. The Liberals lost the election of 1930 to the Conservative Party, led by Richard Bedford Bennett. After

his loss, Mackenzie King stayed on as Opposition Leader, where it was

his policy to refrain from offering advice or alternative policies;

Mackenzie King's policy preferences were not much different from

Bennett's and he let the Conservative government have its way. Though

he gave the impression of sympathy with progressive and liberal causes,

he had no enthusiasm for the New Deal of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt (which Bennett tried to emulate), and he never advocated massive government action to alleviate depression in Canada. In 1935 the Liberals used the slogan "King or Chaos" to win a landslide in the 1935 election.

Promising a much-desired trade treaty with the U.S., the Mackenzie King

government passed the 1935 Reciprocal Trade Agreement. It marked the

turning point in Canadian-American economic relations, reversing the

disastrous trade war of 1930-31, lowing tariffs, and yielding a

dramatic increase in trade; more subtly, it revealed to the prime

minister and the president that they could work together well. The

worst of the Depression had passed by 1935, and King implemented relief

programs such as the National Housing Act and National Employment

Commission. His government also made the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation a crown corporation in 1936, Trans-Canada Airlines (the precursor to Air Canada) in 1937, and the National Film Board of Canada in 1939. In 1938, he changed the Bank of Canada from a private company to a crown corporation. After 1936 the prime minister lost patience when westerners preferred radical alternatives such as the CCF (Co-operative Commonwealth Federation) and Social Credit to

his middle-of-the-road liberalism. Indeed, he came close to writing off

the region with his comment that the prairie dust bowl was "part of the

U.S. desert area. I doubt if it will be of any real use again." Instead

he paid more attention to the industrial regions and the needs of

Ontario and Quebec regarding the proposed St. Lawrence Seaway project

with the United States. As

for the unemployed, he was hostile to federal relief and reluctantly

accepted a Keynesian solution that involved federal deficit spending,

tax cuts and subsidies to the housing market. In March 1936, in response to the German remilitarization of the Rhineland,

King had the Canadian High Commissioner in London inform the British

government that if Britain went to war with Germany over the Rhineland

issue that Canada would remain neutral. In June 1937, during an Imperial Conference of all the Dominion Prime Ministers in London convened during the coronation of King George VI, King informed British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain that

Canada would only go to war if Britain were directly attacked, and that

if Britain were to become involved in a continental war then

Chamberlain was not to expect Canadian support. Also during 1937, King visited Germany and met with Adolf Hitler, becoming the only North American head of government to meet with Hitler. Possessing

a religious yearning for direct insight into the hidden mysteries of

life and the universe, and strongly influenced by the operas of Richard Wagner,

Mackenzie King decided Hitler was a akin to mythical Wagnerian heroes

within whom good and evil were struggling. He thought that good would

eventually triumph and Hitler would redeem his people and lead them to

a harmonious, uplifting future. These spiritual attitudes not only

guided Canada's relations with Hitler but gave the prime minister the

comforting sense of a higher mission, that of helping to lead Hitler to

peace. King commented in his journal that "he is really one who truly

loves his fellow-men, and his country, and would make any sacrifice for

their good". He forecast that "the world will yet come to see a very

great man – mystic in Hitler. [...] I cannot abide in Nazism – the

regimentation – cruelty – oppression of Jews – attitude towards

religion, etc., but Hitler, him – the peasant – will rank some day with

Joan of Arc among the deliverers of his people." In late 1938, during the great crisis in Europe over Czechoslovakia that culminated in the Munich Agreement, Canadians were divided. Francophones insisted on neutrality, as did some top advisers like O.D. Skelton.

Imperialists stood behind Britain and were willing to fight Germany.

Mackenzie King, who served as his own secretary of state for external

affairs (foreign minister), said privately that if he had to choose he

would not be neutral, but he made no public statement. All of Canada

was relieved that the British appeasement at Munich, while sacrificing

the rights of the Czechs, seemed to bring peace. While Minister of Labour, King was appointed to investigate the causes of and claims for compensation resulting from the 1907 Asiatic Exclusion League riots in Vancouver's Chinatown and Japantown.

One of the claims for damages came from Chinese opium manufacturers,

which led King to investigate narcotics use in Vancouver. King became

alarmed upon hearing that white women were also opium users, not just

Chinese men, and he then initiated the process that led to the first

legislation outlawing narcotics in Canada. Under

King's administration, the Canadian government, responding to strong

public opinion, especially in Quebec, refused to expand immigration opportunities for Jewish refugees from Europe. In June 1939 Canada, along with Cuba and the United States, refused to allow the 900 Jewish refugees aboard the passenger ship M.S. St. Louis refuge.

Mackenzie King realized the likelihood of World War II before Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, and began mobilizing on

August 25, 1939, with full mobilization on September 1. Unlike World

War I, however, when Canada was automatically at war as soon as Britain

joined, King asserted Canadian autonomy by waiting until September 10,

a full week after Britain's declaration, when a vote in the House of

Commons took place, to support the government's decision to declare war. Mackenzie

King linked Canada more and more closely to the United States, signing

an agreement with Roosevelt at Ogdensburg, New York, in August 1940

that provided for the close cooperation of Canadian and American

forces. During the war the Americans virtually took control of the

Yukon and Newfoundland in building the Alaska highway and major

airbases.

Mackenzie King — and Canada — were largely ignored by Winston Churchill,

despite Canada's major role in supplying food, raw materials, munitions

and money to the hard-pressed British economy, training airmen for the

Commonwealth, guarding the western half of the North Atlantic against

German U-boats, and providing combat troops for the invasions of Italy,

France and Germany in 1943-45. Mackenzie King proved highly successful in

mobilizing the economy for war, with impressive results in industrial

and agricultural output. The depression ended and prosperity returned.

On the political side, Mackenzie King rejected any notion of a

government of national unity. To

rearm Canada he built the Royal Canadian Air Force as a viable military

power, while at the same time keeping it separate from Britain's Royal

Air Force. He was instrumental in obtaining the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan Agreement, which was signed in Ottawa in December,

1939, binding Canada, Britain, New Zealand, and Australia to a program

that eventually trained half their airmen in the Second World War.

King's government greatly expanded the role of the National Research Council of Canada during the war, moving into full-scale research in nuclear physics and commercial use of nuclear power in the following years. King, with C.D. Howe acting as point man, moved the nuclear group from Montreal to Chalk River, Ontario in 1944, with the establishment of Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories and the residential town of Deep River, Ontario. Canada became a world leader in this field, with the NRX reactor becoming operational in 1947; at the time, NRX was the only operational nuclear reactor outside the United States. King's promise not to impose conscription contributed to the defeat of Maurice Duplessis's Union Nationale Quebec provincial government in 1939 and Liberals' re-election in the 1940 election.

But after the fall of France in 1940, Canada introduced conscription

for home service. Still, only volunteers were to be sent overseas. King

wanted to avoid a repeat of the Conscription Crisis of 1917. By 1942, the military was pressing King hard to send conscripts to Europe. In 1942, King held a national plebiscite on

the issue asking the nation to relieve him of the commitment he had

made during the election campaign. In the House of Commons on 10 June

1942, he said that his policy was "not necessarily conscription but

conscription if necessary." French

Canadians voted against conscription, with over 70% opposed, but an

overwhelming majority – over 80% – of English Canadians supported it.

French and English conscripts were sent to fight in the Aleutian Islands in

1943 – technically North American soil and therefore not "overseas" –

but the mix of Canadian volunteers and draftees found that the Japanese

troops had fled before their arrival. Otherwise, King continued with a

campaign to recruit volunteers, hoping to address the problem with the

shortage of troops caused by heavy losses in the Dieppe Raid in 1942, in Italy in 1943, and after the Battle of Normandy in

1944. In November 1944, the Government decided it was necessary to send

conscripts to Europe. This led to a brief political crisis (Conscription Crisis of 1944) and a mutiny by conscripts posted in British Columbia, but the war ended a few months later. Over 15,000 conscripts went to Europe, though only a few hundred saw combat.

After the start of war with Japan in December 1941 the government oversaw the Japanese-Canadian internment on

Canada’s west coast, which sent 22,000 British Columbia residents of

Japanese descent to relocation camps far from the coast. The reason was

intense public demand for removal and fears of espionage or sabotage. Mackenzie King and his cabinet ignored reports from the RCMP and Canadian military that most of the Japanese were law-abiding and not a threat. Throughout his tenure, King led Canada from a colony with responsible government to an autonomous nation within the British Commonwealth. During the Chanak Crisis of 1922, King refused to support the British without first consulting Parliament, while the Conservative leader, Arthur Meighen,

supported Britain. The British were disappointed with King's response,

but the crisis was soon resolved, as King had anticipated. After the King-Byng Affair, King went to the Imperial Conference of 1926 and argued for greater autonomy of the Dominions. This resulted in the Balfour Declaration 1926, which announced the equal status of all members of the British Commonwealth (as it was known then), including Britain. This eventually led to the Statute of Westminster 1931. The Canadian city of Hamilton hosted the first Empire Games in 1930; this competition later became known as the Commonwealth Games. In

the lead-up to World War II in 1939, King affirmed Canadian autonomy by

saying that the Canadian Parliament would make the final decision on

the issue of going to war. He reassured the pro-British Canadians that

Parliament would surely decide that Canada would be at Britain's side

if Great Britain was drawn into a major war. At the same time, he

reassured those who were suspicious of British influence in Canada by

promising that Canada would not participate in British colonial wars.

His Quebec lieutenant, Ernest Lapointe,

promised French-Canadians that the government would not introduce

conscription; individual participation would be voluntary. In 1939, in

a country which had seemed deeply divided, these promises made it

possible for Parliament to agree almost unanimously to declare war. King

played two roles. On the one hand, he told English Canadians that

Canada would no doubt enter war if Britain did. On the other hand, he

and his Quebec lieutenant Ernest Lapointe told

French Canadians that Canada would only go to war if it was in the

country's best interests. With the dual messages, King slowly led

Canada toward war without causing strife between Canada's two main

linguistic communities. As his final step in asserting Canada's

autonomy, King ensured that the Canadian Parliament made its own

declaration of war one week after Britain. King's government introduced the Canadian Citizenship Act in 1946, which officially created the notion of "Canadian citizens".

Prior to this, Canadians were considered British subjects living in

Canada. On 3 January 1947, King received Canadian citizenship

certificate number 0001. King helped found the United Nations in 1945 and attended the opening meetings in San Francisco.

King became pessimistic about the organization's future possibilities.

After the war, King quickly dismantled wartime controls. Unlike World

War I, press censorship ended with the hostilities. He began an

ambitious program of social programs and laid the groundwork for Newfoundland and Labrador's entry into Canada. King moved Canada into the deepening Cold War in alliance with the U.S. and Britain. He dealt with the espionage revelations of Russian cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko, who defected in Ottawa in 1945 by appointing a Royal Commission to investigate Gouzenko's allegations of a Canadian Communist spy-ring transmitting top secret documents to the Soviet Union. External Affairs minister Louis St. Laurent dealt

decisively with this crisis; St. Laurent's leadership deepened King's

respect, and helped make St. Laurent the next Canadian Prime Minister

three years later. On

20 January 1948, King called on the Liberal Party to hold its first

national convention since 1919 to choose a leader. The August

convention chose Louis St. Laurent as

the new leader of the Liberal Party. Three months later, King retired

after 22 years as prime minister. King also had the most terms (six) as

Prime Minister. Sir John A. Macdonald was second-in-line, with 19

years, as the longest-serving Prime Minister in Canadian History

(1867 – 1873, 1878 – 1891). Mackenzie King was not charismatic and did not

have a large personal following. Only 8 Canadians in 100 picked him

when the Canadian Gallup (CIPO) poll asked in September, 1946, "What

person living in any part of the world today do you admire?"

Nevertheless, his Liberal Party was re-elected in the election of 1945. King

kept a very candid diary from 1893 until his death in 1950. One

biographer called these diaries as "the most important single political document in twentieth-century Canadian history," for they explain motivations of the Canadian war efforts and other events are described in detail. Mackenzie

King was a cautious politician who tailored his policies to prevailing

opinions. "Parliament will decide," he liked to say when pressed to act

and would often say "In times of need all nations face difficult

decisions, Canada is not an exception". Privately, he was highly

eccentric with his preference for communing with spirits, including

those of Leonardo da Vinci, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, his dead mother, and several of his Irish Terrier dogs,

all named Pat except one named Bob. He also claimed to commune with the

spirit of the late President Roosevelt. He sought personal reassurance

from the spirit world, rather than seeking political advice. Indeed,

after his death, one of his mediums said that she had not realized that

he was a politician. King asked whether his party would win the 1935

election, one of the few times politics came up during his seances.

His occult interests were kept secret during his years in office, and

only became publicized later, and have seen in his occult activities a

penchant for forging unities from antitheses, thus having latent

political import. In 1953 Time Magazine stated that he owned — and used — both a Ouija board and a crystal ball. King

never married, but had several close women friends, including Joan

Patteson, a married woman with whom he spent some of his leisure time. Some historians have interpreted passages in his diaries as suggesting that King regularly had sexual relations with prostitutes. Others, also basing their claims on passages of his diaries, have suggested that King was in love with Lord Tweedsmuir, whom he had chosen for appointment as Governor General in 1935.

Mackenzie King died on 22 July 1950, at Kingsmere from pneumonia, with his retirement plans to write his memoirs unfulfilled. He is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto. Unmarried, King is survived by relative Margery King. King was ranked #1, or greatest Canadian Prime Minister, by a survey of Canadian historians.

Mackenzie King lacked the typical personal attributes of great leaders, especially in comparison with Franklin D. Roosevelt of the U.S., Winston Churchill of Britain, Charles de Gaulle of France, or even Joey Smallwood of Newfoundland.

Voters did not love him. He lacked charisma, a commanding presence or

oratorical skills; he did not shine on radio or in newsreels. His best

writing was academic. Cold and tactless in human relations, he had

allies but no close personal friends; he never married and lacked a

hostess whose charm could substitute for his chill. His allies were

annoyed by his constant intrigues. He kept secret his beliefs in

spiritualism and use of mediums to stay in contact with departed

associates and particularly with his beloved mother, and allowed his

intense spirituality to distort his understanding of Hitler. Mackenzie

King remained so long in power because he had remarkable skills that

were exactly appropriate to Canada's needs. He was keenly sensitive to

the nuances of public policy; he was a workaholic with a shrewd and

penetrating intelligence and a profound understanding of how society

and the economy worked. Deeply religious, and inspired by his famous

grandfather, he wanted to uplift the spirit of the people, but at the

same time he understood labour and capital. He had a pitch-perfect ear

for the Canadian temperament and mentality, and was a master of timing.

A modernizing technocrat who regarded managerial mediation as essential

to an industrial society, he wanted his Liberal party to represent

liberal corporatism to create social harmony. Mackenzie King worked

tirelessly and successfully to bring compromise and harmony to many

competing and feuding elements, using politics and government action as

his great instrument. He conducted the Liberal party over 29 years, and

established Canada's international reputation as a middle power fully

committed to world order. His

most famous quote was "A true man does not only stand up for himself,

he stands up for those that do not have the ability to".

In 1918 King, assisted by his friend F.A. McGregor, published the far-sighted book Industry and Humanity: A Study in the Principles Underlying Industrial Reconstruction,

a dense, abstract work that went over the head of most readers but

revealed the practical idealism behind King's political thinking. He

emphasized that capital and labour were natural allies, not foes, and

that the community at large (represented by the government) should be

the third and decisive party in industrial disputes. Quitting

the Foundation in February 1918, Mackenzie King became an independent

consultant on labour issues for the next two years, earning $1000 a

week from leading American corporations. Even so he kept his official

residence in Ottawa, hoping for a call to duty.

In 1919, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Liberal party leader, died, and the first Liberal leadership convention was

held. King entered the contest, and won over a field of four rivals, on

the fourth ballot. He soon returned to parliament in a by-election. King remained leader until 1948.