<Back to Index>

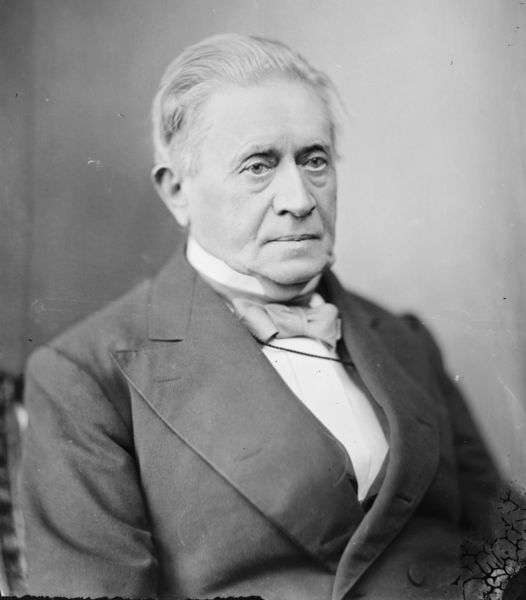

- Physicist Joseph Henry, 1797

- Composer Ludwig van Beethoven, 1770

- Prime Minister of Canada William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1874

PAGE SPONSOR

Joseph Henry (17 December 1797 – 13 May 1878) was an American scientist who served as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, as well as a founding member of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. During his lifetime, he was highly regarded. While building electromagnets, Henry discovered the electromagnetic phenomenon of self-inductance. He also discovered mutual inductance independently of Michael Faraday, though Faraday was the first to publish his results. The SI unit of inductance, the henry, is named in his honor, as are derivative units such as the millihenry and microhenry. Henry's work on the electromagnetic relay was the basis of the electrical telegraph, invented by Samuel Morse and Charles Wheatstone separately.

Henry was born in Albany, New York, to Scottish immigrants Ann Alexander Henry and William Henry. His parents were poor, and Henry's father died while he was still young. For the rest of his childhood, Henry lived with his grandmother in Galway, New York. He attended a school which would later be named the "Joseph Henry Elementary School" in his honor. After school, he worked at a general store, and at the age of thirteen became an apprentice watchmaker and silversmith. Joseph's first love was theater and he came close to becoming a professional actor. His interest in science was sparked at the age of sixteen by a book of lectures on scientific topics titled Popular Lectures on Experimental Philosophy. In 1819 he entered The Albany Academy, where he was given free tuition. He was so poor, even with free tuition, that he had to support himself with teaching and private tutoring positions. He intended to go into the field of medicine, but in 1824 he was appointed an assistant engineer for the survey of the State road being constructed between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. From then on, he was inspired to a career in either civil or mechanical engineering.

Henry excelled at his studies (so much so, that he would often be helping his teachers teach science) and in 1826 he was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at The Albany Academy by Principal T. Romeyn Beck. Some of his most important research was conducted in this new position. His curiosity about terrestrial magnetism led him to experiment with magnetism in general. He was the first to coil insulated wire tightly around an iron core in order to make a more powerful electromagnet, improving on William Sturgeon's electromagnet which used loosely coiled uninsulated wire. Using this technique, he built the strongest electromagnet at the time for Yale. He also showed that, when making an electromagnet using just two electrodes attached to a battery, it is best to wind several coils of wire in parallel, but when using a set-up with multiple batteries, there should be only one single long coil. The latter made the telegraph feasible.

Using his newly-developed electromagnetic principle, Henry in 1831 created one of the first machines to use electromagnetism for motion. This was the earliest ancestor of modern DC motor. It did not make use of rotating motion, but was merely an electromagnet perched on a pole, rocking back and forth. The rocking motion was caused by one of the two leads on both ends of the magnet rocker touching one of the two battery cells, causing a polarity change, and rocking the opposite direction until the other two leads hit the other battery. This apparatus allowed Henry to recognize the property of self inductance. British scientist Michael Faraday also recognized this property around the same time; since Faraday published his results first, he became the officially recognized discoverer of the phenomenon.

In 1848 Henry worked in conjunction with Professor Stephen Alexander to determine the relative temperatures for different parts of the solar disk. They used a thermopile to determine that sunspots were cooler than the surrounding regions. This work was shown to the astronomer Angelo Secchi who extended it, but with some question as to whether Henry was given proper credit for his earlier work. Prof. Henry was introduced to Prof. Thaddeus Lowe,

a balloonist from New Hampshire who had taken interest in the

phenomenon of lighter-than-air gases, and exploits into meteorology, in

particular, the high winds which we call the Jet stream today.

It was Lowe's intent to make a transatlantic crossing by utilizing an

enormous gas-inflated aerostat. Henry took a great interest in Lowe's

endeavors, promoting him among some of the more prominent scientists

and institutions of the day. In June 1860, Lowe had made a successful test flight with his gigantic balloon, first named the City of New York and later renamed The Great Western, flying from Philadelphia to Medford, New York.

Lowe would not be able to attempt a transatlantic flight until late

Spring of 1861, so Henry convinced him to take his balloon to a

point more West and fly the balloon back to the eastern seaboard, an

exercise that would keep his investors interested. Lowe took several smaller balloons to Cincinnati, Ohio, in March 1861. On 19 April, he launched on a fateful flight that landed him in Confederate South Carolina.

With the Southern States seceding from the union, and the onset of

civil war, Lowe abandoned further attempts at a transatlantic crossing

and, with Henry's endorsement, went to Washington to offer his services

as an aeronaut to the Federal government. Henry submitted a letter to

Secretary of War Simon Cameron which carried Henry's endorsement: On Henry's recommendation Lowe went on to form the Union Army Balloon Corps and served two years with the Army of the Potomac as a Civil War Aeronaut. Over 150 years ago, Henry identified the room acoustics phenomena

we now call direct sound, early reflections, and reverberation. He

demonstrated the early sound integration period and laid the groundwork

for further fundamental research on early reflections that was not

followed up until the work at Göttingen University in the 1950–1960s. He brought a robust scientific approach to the subject of acoustics. Henry

devised a simple experiment to demonstrate the integration of direct

and early sound. A listener, standing in an open space 100 feet from a

wall, claps his hands and hears an echo. He gradually approaches the

wall, clapping, until no echo is perceived, at a distance of 30

feet — the "Henry Distance" — equating to an early sound integration time

of 60 ms. As

a famous scientist and director of the Smithsonian Institution, Henry

received visits from other scientists and inventors who sought his

advice. Henry was patient, kindly, self-controlled, and gently humorous. One such visitor was Alexander Graham Bell who

on 1 March 1875 carried a letter of introduction to Henry. Henry showed

an interest in seeing Bell's experimental apparatus and Bell returned

the following day. After the demonstration, Bell mentioned his untested

theory on how to transmit human speech electrically by means of a "harp

apparatus" which would have several steel reeds tuned to different

frequencies to cover the voice spectrum. Henry said Bell had "the germ

of a great invention". Henry advised Bell not to publish his ideas

until he had perfected the invention. When Bell objected that he lacked

the necessary knowledge, Henry firmly advised: "Get it!" On

25 June 1876, Bell's experimental telephone (using a different design)

was demonstrated at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia where

Henry was one of the judges for electrical exhibits. On 13 January

1877, Bell demonstrated his instruments to Henry at the Smithsonian

Institution and Henry invited Bell to demonstrate them again that night

at the Washington Philosophical Society. Henry praised "the value and astonishing character of Mr. Bell's discovery and invention." Henry died on 13 May 1878, and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in the Georgetown section of northwest Washington, D.C.