<Back to Index>

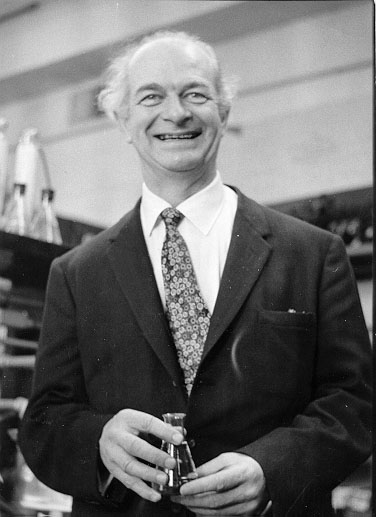

- Chemist Linus Carl Pauling, 1901

- Architect Elias Holl, 1573

- Commander Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Gozon, 1712

Linus Carl Pauling (February 28, 1901 – August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, peace activist, author, and educator. He was one of the most influential chemists in history and ranks among the most important scientists in any field of the 20th century. Pauling was among the first scientists to work in the fields of quantum chemistry, molecular biology, and orthomolecular medicine. He is one of only four individuals to have won multiple Nobel Prizes. He is one of only two people to have been awarded a Nobel Prize in two different fields (the Chemistry and Peace prizes), the other being Marie Curie (the Chemistry and Physics prizes), and the only person to have been awarded each of his prizes without sharing it with another recipient.

Pauling was born in Portland, Oregon, as the first born child to Herman Henry William Pauling (1876–1910) and Lucy Isabelle "Belle" Darling (1881–1926). He was named "Linus Carl", in honor of Lucy's father, Linus, and Herman's father, Carl. Herman and Lucy—then 23 and 18 years old, respectively—had met at a dinner party in Condon. Six months later, the two were married. Linus Pauling spent his first year living in a one-room apartment with his parents in Portland. In 1902, after his sister Pauline was born, Pauling's parents decided to move out of the city. They were crowded in their apartment, but couldn't afford more spacious living quarters in Portland. Lucy stayed with her husband's parents in Oswego, while Herman searched for new housing. Herman brought the family to Salem, where he took up a job as a traveling salesman for the Skidmore Drug Company. Within a year of Lucile's birth in 1904, Herman Pauling moved his family to Oswego, where he opened his own drugstore. The business climate in Oswego was poor, so he moved his family to Condon in 1905.

In 1909, Pauling's grandfather, Linus, divorced his second wife and married a young schoolteacher, almost the same age as his daughter Lucy. A few months later, he died of a heart attack, brought on by complications from nephritis. Meanwhile, Herman Pauling was suffering from poor health and had regular sharp pains in his abdomen. Lucy's sister, Abbie, saw that Herman was dying and immediately called the family physician. The doctor gave Herman a sedative to reduce the pain, but it only offered temporary relief. His health worsened in the coming months and finally died of a perforated ulcer on June 11, 1910, leaving Lucy to care for Linus, Lucile and Pauline.

Linus was a voracious reader as a child, and at one point his father wrote a letter to The Oregonian inviting suggestions of additional books to occupy his time. Pauling

first planned to become a chemist after being amazed by experiments

conducted with a small chemistry lab kit by his friend, Lloyd A.

Jeffress. In

high school, Pauling continued to conduct chemistry experiments,

borrowing much of the equipment and material from an abandoned steel

plant. With an older friend, Lloyd Simon, Pauling set up Palmon

Laboratories. Operating from Simon's basement, the two young adults

approached local dairies to offer their services in performing

butter fat samplings at cheap prices. Dairymen were wary of trusting two

young boys with the task, and as such, the business ended as a failure. By

the fall of 1916, Pauling was a 15-year-old high school senior and had

enough credits to enter Oregon Agricultural College (OAC, now known as Oregon State University) in Corvallis. However, he did not have enough credits for two required American history courses that would satisfy his requirement to earn a high school diploma.

He asked the school principal if he could take these courses

concurrently during the spring semester. The principal denied his

request, and Pauling decided to leave the school in June without a

diploma. His high school, Washington High School in Portland, awarded him the diploma 45 years later, after he had won two Nobel Prizes. During the summer, Pauling worked part-time at a grocery store, earning eight dollars a

week. His mother set him up with an interview with a Mr.

Schwietzerhoff, the owner of a number of manufacturing plants in

Portland. Pauling was hired as an apprentice machinist with a salary of

40 dollars a month. Pauling excelled at his job, and saw his salary

increase to 50 dollars a month after being on the job for only a month. In

his spare time, he set up a photography lab with two friends and found

business from a local photography company. He hoped that the business

would earn him enough money to pay for his future college expenses. Pauling received a letter of admission from OAC in September 1917 and immediately gave notice to his boss and told his mother of his plans. In October 1917, Pauling entered Oregon Agricultural College and lived in a boarding house on

campus with his cousin Mervyn and another man, using the $200 he had

saved from odd jobs to finance his education. In his first semester,

Pauling registered for two courses in chemistry, two in mathematics,

mechanical drawing, introduction to mining and use of explosives,

modern English prose, gymnastics and military drill. Pauling

fell in love with a freshman girl named Irene early in the school year.

By the end of October, he had used up $150 of his savings on her,

taking her to shows and games. He soon got a job at the girls'

dormitory, working 100 hours a month chopping wood for stoves, cutting

up beef and mopping up the kitchen. Despite the 25 cent per hour

salary, Pauling was still having trouble managing his finances. He

began eating one hot meal a day at a restaurant off campus to minimize

his expenses. Pauling was active in campus life and founded the school's chapter of the Delta Upsilon fraternity. After

his second year, he planned to take a job in Portland to help support

his mother, but the college offered him a position teaching quantitative analysis,

a course he had just finished taking himself. He worked forty hours a

week in the laboratory and classroom and earned $100 a month. This allowed him to continue his studies at the college. In his last two years at school, Pauling became aware of the work of Gilbert N. Lewis and Irving Langmuir on the electronic structure of atoms and their bonding to form molecules. He decided to focus his research on how the physical and chemical properties of

substances are related to the structure of the atoms of which they are

composed, becoming one of the founders of the new science of quantum chemistry.

Pauling began to neglect his studies in humanities and social sciences.

He had also exhausted the course offerings in the physics and

mathematics departments. Professor Samuel Graf selected Pauling to be

his teaching assistant in a high-level mathematics course. During the winter of his senior year, Pauling was approached by the college to teach a chemistry course for home economics majors. It was in one of these classes that Pauling met his future wife, Ava Helen Miller. In 1922, Pauling graduated from OAC with a degree in chemical engineering and went on to graduate school at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California, under the guidance of Roscoe G. Dickinson. His graduate research involved the use of X-ray diffraction to determine the structure of crystals. He published seven papers on the crystal structure of minerals while he was at Caltech. He received his Ph. D. in physical chemistry and mathematical physics, summa cum laude, in 1925. Pauling had first been exposed to the concepts of quantum theory and quantum mechanics while he was studying at Oregon State University. He later traveled to Europe on a Guggenheim Fellowship, which was awarded to him in 1926, to study under German physicist Arnold Sommerfeld in Munich, Danish physicist Niels Bohr in Copenhagen, and Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger in Zürich.

All three were experts working in the new field of quantum mechanics

and other branches of physics. Pauling became interested in seeing how

quantum mechanics might be applied in his chosen field of interest, the electronic structure of atoms andmolecules. In Europe, Pauling was also exposed to one of the first quantum mechanical analyses of bonding in the hydrogen molecule, done by Walter Heitler and Fritz London.

Pauling devoted the two years of his European trip to this work and

decided to make it the focus of his future research. He became one of

the first scientists in the field of quantum chemistry and a pioneer in the application of quantum theory to the structure of molecules. He also joined Alpha Chi Sigma, the professional chemistry fraternity. In 1927, Pauling took a new position as an assistant professor at Caltech in theoretical chemistry. He launched his faculty career with a very productive five years, continuing with his X-ray crystal

studies and also performing quantum mechanical calculations on atoms

and molecules. He published approximately fifty papers in those five

years, and created five rules now known as Pauling's Rules. By 1929, he was promoted to associate professor, and by 1930, to full professor. In 1931, the American Chemical Society awarded Pauling the Langmuir Prize for the most significant work in pure science by a person 30 years of age or younger. The following year, Pauling published what he regarded as his most important paper, in which he first laid out the concept of hybridization of atomic orbitals and analyzed the tetravalency of the carbon atom. At Caltech, Pauling struck up a close friendship with theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer, who was spending part of his research and teaching schedule away from U.C. Berkeley at

Caltech every year. The two men planned to mount a joint attack on the

nature of the chemical bond: apparently Oppenheimer would supply the

mathematics and Pauling would interpret the results. However, their

relationship soured when Pauling began to suspect that Oppenheimer was

becoming too close to Pauling's wife, Ava Helen. In the summer of 1930, Pauling made another European trip, during which he learned about the use of electrons in diffraction studies similar to the ones he had performed with X-rays. After returning, he built an electron diffraction instrument at Caltech with a student of his, L. O. Brockway, and used it to study the molecular structure of a large number of chemical substances. Pauling introduced the concept of electronegativity in 1932. Using the various properties of molecules, such as the energy required to break bonds and the dipole moments of molecules, he established a scale and an associated numerical value for most of the elements—the Pauling Electronegativity Scale—which is useful in predicting the nature of bonds between atoms in molecules. Pauling had been practically apolitical until World War II,

but the aftermath of the war and his wife's pacifism changed his life

profoundly, and he became a peace activist. During the beginning of the Manhattan Project, Robert Oppenheimer invited

him to be in charge of the Chemistry division of the project, but he

declined, not wanting to uproot his family. He did work on other

projects that had military applications such as explosives, rocket

propellants, an oxygen meter for submarines and patented an armor

piercing shell and was awarded a Presidential Medal of Merit. In 1946, he joined the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, chaired by Albert Einstein. Its

mission was to warn the public of the dangers associated with the

development of nuclear weapons. His political activism prompted the U.S. State Department to deny him a passport in 1952, when he was invited to speak at a scientific conference in London. His passport was restored in 1954, shortly before the ceremony in Stockholm where he received his first Nobel Prize. Joining Einstein, Bertrand Russell and eight other leading scientists and intellectuals, he signed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto in 1955. In

1958, Pauling joined a petition drive in cooperation with the founders

of the St. Louis Citizen's Committee for Nuclear Information (CNI).

This group, headed by Washington University professors Barry Commoner, Eric Reiss, M. W. Friedlander, and John Fowler, set up a study of radioactive strontium-90 in the baby teeth of

children across North America. The "Baby Tooth Survey," headed by

Dr.Louise Z. Reiss, demonstrated conclusively in 1961 that above-ground

nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout spread primarily via milk from cows that had ingested contaminated grass. Pauling also participated in a public debate with the atomic physicist Edward Teller about the actual probability of fallout causing mutations. In 1958, Pauling and his wife presented the United Nations with the petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to nuclear-weapon testing.

Public pressure and the frightening results of the CNI research

subsequently led to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons

testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. On the day that the treaty went into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize. Many

of Pauling's critics, including scientists who appreciated the

contributions that he had made in chemistry, disagreed with his

political positions and saw him as a naive spokesman for Soviet communism. He was ordered to appear before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee,

which termed him "the number one scientific name in virtually every

major activity of the Communist peace offensive in this country." An

extraordinary headline in Life magazine characterized his 1962 Nobel Prize as "A Weird Insult from Norway". Pauling was awarded the International Lenin Peace Prize by the USSR in 1970.