<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Karl Raimund Popper, 1902

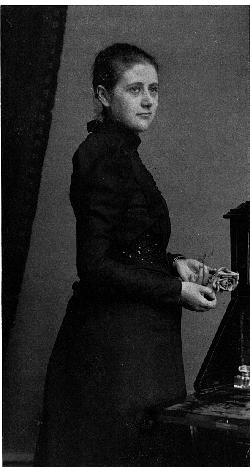

- Author Helen Beatrix Potter, 1866

- President of Peru Alberto Ken'ya Fujimori Fujimori, 1938

Helen Beatrix Potter (28 July 1866 – 22 December 1943) was an English author, illustrator, mycologist and conservationist best known for children's books featuring anthropomorphic characters such as in The Tale of Peter Rabbit.

Born into a privileged household, Potter was educated by governesses and grew up isolated from other children. She had numerous pets but as well because of holidays spent in Scotland and the Lake District,

developed a love of landscape, flora and fauna, all of which she

closely observed and painted. Her parents discouraged her intellectual

development as a young woman, but her study and watercolors of fungi led to her being widely respected in the field of mycology. In her thirties, Potter published the highly successful children's book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Around that time she became secretly engaged to her publisher Norman Warne.

This caused a breach with her parents, who disapproved of her marrying

someone of lower social status. Warne died before the wedding could

take place. Potter

began writing and illustrating children's books full time. With

proceeds from the books, she became financially independent of her

parents and was eventually able to buy Hill Top Farm in

the Lake District. She extended the property with other purchases over

time. In her forties, she married William Heelis, a local solicitor,

became a sheep breeder and farmer while continuing to write and

illustrate books for children. She published twenty-three books. Potter

died on 22 December 1943, and left almost all of her property to

the National Trust.

Her books continue to sell well throughout the world, in multiple

languages. Her stories have been retold in various formats including ballet, films, and in animation. Beatrix Potter was born in South Kensington,

London on 28 July, 1866. Educated at home by a succession of

governesses, she had little opportunity to mix with other children.

Even her younger brother, Bertram, was rarely at home; he was sent as a

boy to boarding school, leaving Beatrix alone with her many pets. She

had frogs, newts, ferrets and even a pet bat. She also had two rabbits

— the first was Benjamin, whom she described as "an impudent, cheeky

little thing", while the second was Peter, whom she took everywhere

with her on a little lead, even on the occasional outing. Potter

watched the animals for hours on end, sketching them and developing her

abilities as an artist. Beatrix Potter's father was Rupert William Potter (1832–1914), son of Edmund Potter. Rupert trained as a barrister, but spent his days at gentlemen's clubs and

rarely practised law. Her mother, Helen Potter née Leech

(1839–1932), the daughter of a cotton merchant, spent her time visiting

or receiving visitors. The family was supported by both parents'

inherited incomes. Every summer, Rupert Potter would rent a country house; Dalguise House in Perthshire, Scotland for the eleven summers of 1871 to 1881, then later, Lindeth Howe in the English Lake District where Potter illustrated The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes and The Tale of Pigling Bland. In 1882, the family met the local vicar, Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, who was deeply worried about the effects of industry and tourism on the Lake District. He would later found the National Trust in

1895, to help protect the countryside. Potter had immediately fallen in

love with the rugged mountains and dark lakes. Through Rawnsley, she

learnt of the importance of trying to conserve the region, a

sensibility that was to stay with her for her entire life. When

Potter came of age, her parents appointed her as their housekeeper and

discouraged any intellectual development, instead requiring her to

supervise the household. From the age of 15 until she was past 30, she

recorded her everyday life in journals, using her own secret code which was not decoded until 20 years after her death. Her uncle attempted to introduce her as a student at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, but she was rejected because she was a woman. Potter was later one of the first to suggest that lichens were a symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae. As,

at the time, the only way to record microscopic images was by painting

them, Potter made numerous drawings of lichens and fungi. As the result

of her observations, she was widely respected throughout England as an

expert mycologist. She also studied spore germination and life cycles of fungi. Potter's set of detailed watercolours of fungi, numbering some 270 completed by 1901, is in the Armitt Library, Ambleside. In 1897, her paper "On the Germination of Spores of Agaricineae" was presented to the Linnean Society by her uncle Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe,

as women were barred from attending meetings. (In 1997, the Society

issued a posthumous official apology to Potter for the way she had been

treated.) The Royal Society also refused to publish at least one of her technical papers. She also lectured at the London School of Economics several times. Potter had drawn, for her own enjoyment, illustrations for Joel Chandler Harris's Uncle Remus stories, and she was probably inspired by these as well as by the European tradition of animal fables going back to Aesop.

The basis of her many projects and stories were the small animals which

she smuggled into the house or observed during family holidays in

Scotland and the Lake District.

When she was 27 and on one such holiday in Scotland, in a letter dated

4 September 1893 she sent a picture and story letter about rabbits to

Noel Moore, the five-year-old son of her last governess, Annie (Carter)

Moore. Moore was the first to recognize the literary and commercial

value of Potter's picture and story letter and encouraged her to

publish the story. She borrowed back the letter in 1901, developed and expanded the tale, and made it into the book titled The Tale of Peter Rabbit and Mr. McGregor's Garden. She

sent her slightly rewritten picture letters to six publishers, but was

turned down by all of them. The primary complaint from all of them was

the lack of colour pictures, which were popular at the time. In

September 1901, she decided to self-publish and distribute 250 copies

of a renamed The Tale of Peter Rabbit.

Later that year, because the colour printing blocks were already

created and other children’s books were popular, she finally attracted

the publisher Frederick Warne & Co. The publishing contract was signed in June 1902 and, by the end of the year, 28,000 copies were in print. Later, the character Peter Rabbit was patented and produced as a soft toy in 1903. This makes Peter the oldest licensed character. She followed Peter Rabbit with The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin in

1903, that was also based on an earlier letter to one of the Moore

children. Such was the popularity of these and her subsequent books

that she gained an independent income from their sales. She also became

secretly engaged to the publisher, Norman Warne in 1905, but her

parents were set against her marrying a tradesman. Their opposition to

the wedding caused a breach between Beatrix and her parents. The

wedding was not to be, for soon after the engagement, Norman fell ill of pernicious anemia and

died within a few weeks. Beatrix was devastated. She wrote in a letter

to his sister, Millie, "He did not live long, but he fulfilled a useful

happy life. I must try to make a fresh beginning next year." Potter

eventually wrote 23 books, all in the same small format. Part of the

popularity of her books was due to the quality of her illustrations:

the animal characters are portrayed as full of personality, but are

deeply based in natural actions. Her writing efforts finally abated

around 1920 due to poor eyesight. The Tale of Little Pig Robinson was

published in 1930; however, the actual manuscript was one of the first

to be written and much predates this publication date. After Warne's death, Potter purchased Hill Top Farm in the village of Sawrey (then in Lancashire, now in Cumbria), in the Lake District. She loved the landscape, and visited the farm as often as she could, discussing the set-up with farm manager John Cannon. With the steady stream of royalties from her books, she began to buy pieces of land under the guidance of local solicitor William

Heelis. In 1913 at the age of 47, Potter married Heelis and moved to

Hill Top Farm permanently. Some of Potter's best-loved works show the

Hill Top farmhouse and the village. While the couple had no children,

the farm was constantly alive with dogs, cats and even a pet hedgehog

named "Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle". On moving to the Lake District, Potter became engrossed in breeding and showing Herdwick sheep. She

became a respected farmer, a judge at local agricultural shows, and

President of the Herdwick Sheep Breeders' Association. When Potter's

parents died, she used her inheritance to buy more farms and tracts of

land. After some years, Potter and Heelis moved down into the village

of Sawrey, and into Castle Cottage — where the local children knew her

for her grumpy demeanour, and called her "Auld Mother Heelis". Her letters of the time reflect her increasing concerns with her sheep, preservation of farmland, and World War II. Beatrix Potter died at Castle Cottage in Sawrey on 22 December 1943. Her body was cremated at Carleton Crematorium, Blackpool and her ashes were scattered in the countryside near Sawrey. In her will, Potter left almost all of her property to the National Trust — 4,000 acres (16 km²) of land, cottages, and 15 farms. The legacy has helped ensure that the Lake District and the practice of fell farming remain unspoiled to this day. Her properties now lie within the Lake District National Park. The Trust's 2005 Swindon headquarters are named "Heelis" in her honour. Her literary estate is owned by Chorion, a media rights company that specialises in classic British children's characters. Beatrix Potter Gallery, a gallery run by the National Trust and situated in a 17th-century Lake District townhouse in Hawkshead, Cumbria, England, now displays her original book illustrations.