<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Karl Raimund Popper, 1902

- Author Helen Beatrix Potter, 1866

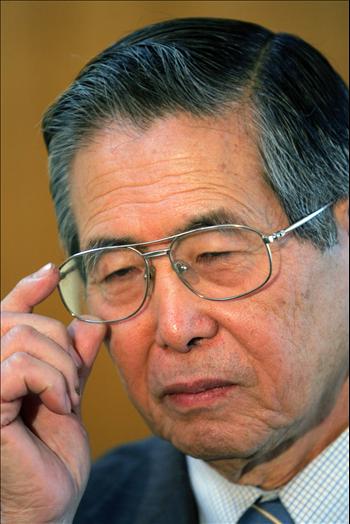

- President of Peru Alberto Ken'ya Fujimori Fujimori, 1938

Alberto Ken'ya Fujimori Fujimori (born in Lima on July 28, 1938) served as President of Peru from July 28, 1990, to November 17, 2000. A controversial figure, Fujimori has been credited with uprooting terrorism in Peru and restoring its macroeconomic stability, though his methods have drawn charges of authoritarianism and human rights violations. Even amidst his 2008 prosecution for "crimes against humanity" relating to his presidency, two-thirds of Peruvians polled voiced approval for his leadership in that period.

A Peruvian of Japanese descent, Fujimori fled to Japan in 2000 amidst a corruption scandal, where he attempted to resign his presidency. His resignation was rejected by the Congress of the Republic,

which preferred to remove him from office by force of vote. Wanted in

Peru on charges of corruption and human rights abuses, Fujimori

maintained a self-imposed exile abroad until his detainment during a

visit to Chile in November 2005. He was finally extradited to face criminal charges in Peru in September 2007. In December 2007, Fujimori was convicted of ordering an illegal search and seizure, and was sentenced to six years in prison. The Supreme Court upheld the decision, upon his appeal. On

April 7, 2009, Fujimori was convicted of human rights violations and

sentenced to 25 years in prison for his role in killings and

kidnappings by the Grupo Colina death squad during

his government's battle against leftist guerrillas in the 1990s. The

verdict delivered by a three-judge panel marked the first time that an

elected head of state has been extradited back to his home country,

tried, and convicted of human rights violations. Fujimori was

specifically found guilty of murder, bodily harm, and two cases of

kidnapping. On July 20, 2009, a Peruvian court sentenced Alberto Fujimori to an additional 71⁄2 years in prison for embezzlement after the former president admitted paying his spy chief $15 million in state funds. He later pled guilty to bribery. According to government records, Fujimori was born on July 28, 1938, in Miraflores, a district of Lima. His parents, Naoichi Fujimori (1897–1971) and Mutsue Inomoto de Fujimori (1913–2009), were natives of Kumamoto, Japan, who emigrated to Peru in 1934. He holds dual Peruvian and Japanese citizenship, his parents having secured the latter through the Japanese Consulate. In July 1997, the political magazine Caretas charged that Fujimori had actually been born in Japan. Because

Peru's constitution requires the president to have been born in Peru,

this would have made Fujimori ineligible to be president. The magazine, which had been sued for libel by Vladimiro Montesinos seven years earlier, reported that Fujimori's birth and baptismal certificates might have been altered. Caretas also alleged that Fujimori's mother declared having two children when she entered Peru; Fujimori is the second of four children. Caretas' contentions were hotly contested in the Peruvian media; the magazine Sí, for instance, described the allegations as "pathetic" and "a dark page for [Peruvian] journalism". Latin

American scholars Cynthia McClintock and Fabián Vallas note that

the issue appeared to have died down among Peruvians after the Japanese

government announced in 2000 that "Fujimori's parents had registered

his birth in the Japanese consulate in Lima". Fujimori obtained his early education at the Colegio Nuestra Señora de la Merced and La Rectora. Fujimori's

parents were Buddhists, but he was baptised and raised as a Roman

Catholic. He spoke mainly Japanese at home, and became a proficient

Spanish speaker during his years at school. In 1956, Fujimori graduated high school from La gran unidad escolar Alfonso Ugarte in Lima. He went on to undergraduate studies at the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina in 1957, graduating in 1961 first in his class as an agricultural engineer. There he lectured on mathematics the following year. In 1964 he went on to study physics at the University of Strasbourg in France. On a Ford scholarship, Fujimori also attended the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee in the United States, where he obtained his master's degree in mathematics in 1969. In 1974, he married Susana Higuchi, also a Peruvian of Japanese descent. They had four children, including a daughter, Keiko, who followed her father into politics. In recognition of his academic achievements, the sciences faculty of the Universidad Nacional Agraria offered Fujimori the deanship and in 1984 appointed him to the rectorship of the university, which he held until 1989. In 1987, Fujimori also became president of the National Commission of Peruvian University Rectors (Asamblea Nacional de Rectores), a position which he has held twice. He also hosted a TV show called "Concertando" from 1987 to 1989, on Peru's state-owned network, Channel 7. A dark horse candidate, Fujimori won the 1990 presidential election under the banner of the new party Cambio 90 ("cambio" meaning "change"), beating world-renowned writer Mario Vargas Llosa in a surprising upset. He capitalized on profound disenchantment with previous president Alan García and his American Popular Revolutionary Alliance party

(APRA). He exploited popular distrust of Vargas Llosa's identification

with the existing Peruvian political establishment, and uncertainty

about Vargas Llosa's plans for neoliberal economic

reforms. Fujimori won much support from the poor, who had been

frightened by Vargas Llosa's austerity proposals. During the campaign,

Fujimori was nicknamed El Chino, which roughly translates to "Chinaman"; it is common for people of any East Asian descent to be called chino in Peru, as elsewhere in Latin America,

both derogatively and affectionately. Although he is of Japanese

heritage, Fujimori has suggested that he was always gladdened by the

term, which he perceived as a term of affection. With his election victory, he became the first person of East Asian descent to become head of government of a Latin American nation, and just the third of East Asian descent to govern a South American state, after Arthur Chung of Guyana and Henk Chin A Sen of Suriname (each of whom had served as head of state, rather than head of government). During his first term in office, Fujimori enacted wide-ranging neoliberal reforms, known as Fujishock. During the presidency of Alan García,

the economy had entered a period of hyperinflation and the political

system was in crisis due to the country's internal conflict, leaving

Peru in "economic and political chaos". It

was Fujimori's objective to pacify the nation and restore economic

balance. Even though this program bore little resemblance to his

campaign platform and was in fact more drastic than anything Vargas

Llosa had proposed, the Fujishock succeeded in restoring Peru to the global economy, though not without immediate social cost. Fujimori's initiative relaxed private sector price controls,

drastically reduced government subsidies and government employment,

eliminated all exchange controls, and also reduced restrictions on

investment, imports, and capital flow. Tariffs

were radically simplified, the minimum wage was immediately quadrupled,

and the government established a $400 million poverty relief fund. The

latter measure seemed to anticipate the economic agony that was to

come, as electricity costs quintupled, water prices rose eightfold, and

gasoline prices rose 3000%. The IMF was impressed by these measures, and guaranteed loan funding for Peru. Inflation began to fall rapidly and foreign investment capital flooded in. Fujimori's privatization campaign

featured the selling off of hundreds of state-owned enterprises, and

the replacing of the country's troubled currency, the inti, with the Nuevo Sol. The Fujishock restored macroeconomic stability to the economy and triggered a considerable long-term economic upturn in the mid-1990s. In 1994, the Peruvian economy grew at a rate of 13%, faster than any other economy in the world. During Fujimori's first term in office, APRA and Vargas Llosa's party, FREDEMO, remained in control of both chambers of Congress (the Chamber of Deputies and Senate),

hampering the government's ability to enact economic reforms. Fujimori

also found it difficult to combat the threat posed by the Maoist guerrilla organization Shining Path (Spanish: Sendero Luminoso),

due largely to what he perceived to be the intransigence and

obstructionism of Congress. By March 1992, Congress met with the

approval of only 17% of the electorate, according to one poll (the

presidency stood at 42%, in the same poll). In response to the political deadlock, on April 5, 1992, Fujimori with the support of the military carried out a presidential coup d'état, also known as the autogolpe (auto-coup or self-coup) or Fujigolpe (Fuji-coup) in Peru. He shut down Congress, suspended the constitution, and purged the judiciary. The coup was welcomed by the public, according to numerous polls. Not

only was the coup itself marked by favorable public opinion in several

independent polls, but also public approval of the Fujimori

administration jumped significantly in the wake of the coup. Fujimori

often cited this public support in defending the coup, which he

characterized as "not a negation of real democracy, but on the

contrary... a search for an authentic transformation to assure a

legitimate and effective democracy." Fujimori believed that Peruvian democracy had been nothing more than "a deceptive formality – a facade"; he

claimed the coup was necessary to break with the deeply entrenched

special interests that were hindering him from rescuing Peru from the

chaotic state in which García had left it. Fujimori's coup was immediately met with the near-unanimous condemnation by the international community. The Organization of American States denounced the coup and demanded a return to "representative democracy", despite Fujimori's claims that his coup represented a "popular uprising". Various foreign ministers of OAS member states reiterated this condemnation of the autogolpe. They proposed an urgent effort to promote the re-establishment of "the democratic institutional order" in Peru. Following

negotiations involving the OAS, the government, and opposition groups,

Alberto Fujimori's initial response was to hold a referendum to ratify

the auto-coup, which the OAS rejected. Fujimori then proposed

scheduling elections for a Democratic Constituent Congress (CCD), which

would be charged with drafting a new constitution, to be ratified by a

national referendum. Despite the lack of consensus among political

forces in Peru regarding this proposal, the ad hoc OAS

meeting of ministers nevertheless approved Fujimori’s offer in mid-May,

and elections for the CCD were held on November 22, 1992. Various states acted to condemn the coup individually. Venezuela broke off diplomatic relations, and Argentina withdrew its ambassador. Chile joined Argentina in requesting that Peru be suspended from the Organization of American States. International financiers delayed planned or projected loans, and the United States, Germany and Spain suspended

all non-humanitarian aid to Peru. The coup appeared to threaten the

economic recovery strategy of reinsertion, and complicated the process

of clearing arrears with the International Monetary Fund. Whereas Peruvian–U.S. relations early in Fujimori's presidency had been dominated by questions of coca eradication, Fujimori's autogolpe immediately

became a major obstacle to international relations, as the United

States immediately suspended all military and economic aid to Peru,

with exceptions for counter-narcotic and humanitarian-related funds. Two weeks after the self-coup, the George H.W. Bush administration changed its position and officially recognized Fujimori as the legitimate leader of Peru. With FREDEMO dissolved and APRA's leader, Alan García, exiled to Colombia, Fujimori sought to legitimize his position. He called elections for a Democratic Constitutional Congress that would serve as a legislature and a constituent assembly. While APRA and Popular Action attempted

to boycott this, the Popular Christian Party and many left-leaning

parties participated in this election. His supporters won a majority in

this body, and drafted a new constitution in

1993. A referendum was scheduled, and the coup and the Constitution of

1993 were approved by a narrow margin of between four and five percent.

Later in the year, on November 13, there was a failed military coup,

led by General Jaime Salinas. Salinas asserted that his efforts were a matter of turning Fujimori over for trial, for violating the Peruvian constitution. In 1994, Fujimori separated from his wife Susana Higuchi in a noisy, public divorce. He formally stripped her of the title First Lady in

August 1994, appointing their elder daughter First Lady in her stead.

Higuchi publicly denounced Fujimori as a "tyrant" and claimed that his

administration was corrupt. They formally divorced in 1995. The

1993 Constitution allowed Fujimori to run for a second term, and in

April 1995, at the height of his popularity, Fujimori easily won

reelection with almost two-thirds of the vote. His major opponent,

former Secretary-General of the United Nations Javier Pérez de Cuéllar,

won only 22 percent of the vote. His supporters won control of the

legislature. One of the first acts of the new congress was to declare

an amnesty for all members of the Peruvian military or police accused

or convicted of human rights abuses between 1980 and 1995. During his second term, Fujimori signed a peace agreement with Ecuador over a border dispute that

had simmered for more than a century. The treaty allowed the two

countries to obtain international funds for developing the border

region. Fujimori also settled unresolved issues with Chile, Peru's

southern neighbor, still outstanding since the Treaty of Lima of

1929. The

1995 election was the turning point in Fujimori's career. Peruvians now

began to be more concerned about freedom of speech and the press.

However, before he was sworn in for a second term, Fujimori stripped

two universities of their autonomy and reshuffled the national

electoral board. According

to a poll by the Peruvian Research and Marketing Company conducted in

1997, 40.6% of Lima residents considered President Fujimori an

authoritarian. In

addition to the nature of democracy under Fujimori, Peruvians were

becoming increasingly interested in the myriad criminal allegations

involving Fujimori and his chief of the National Intelligence Service, Vladimiro Montesinos.

A 2002 report by Health Minister Fernando Carbone would later suggest

that Fujimori had played a role in pressuring 200,000 indigenous people

in rural areas into being sterilized from 1996 to 2000, as part of a

population control program. A 2004 World Bank publication

would suggest that, in this period, Montesinos' abuse of the power

accorded him by Fujimori "led to a steady and systematic undermining of

the rule of law". The

1993 constitution limits a presidency to two terms. Shortly after

Fujimori began his second term, his supporters in Congress passed a law

of "authentic interpretation" which effectively allowed him to run for

another term in 2000. A 1998 effort to repeal this law by referendum

failed. In

late 1999, Fujimori announced that he would run for a third term.

Peruvian electoral bodies, which were politically sympathetic to

Fujimori, accepted his argument that the two-term restriction did not

apply to him, as it was enacted while he was already in office. Exit

polls showed Fujimori well short of the 50% required to avoid an

electoral runoff, but the first official results showed him with 49.6%

of the vote, just short of outright victory. Eventually, Fujimori was

credited with 49.89% — 20,000 votes short of avoiding a runoff. Despite

reports of numerous irregularities, the international observers

recognized an adjusted victory of Fujimori. His primary opponent, Alejandro Toledo,

called for his supporters to spoil their ballots in the runoff by

writing "No to fraud!" on them (voting is mandatory in Peru).

International observers pulled out of the country after Fujimori

refused to delay the runoff. In

the runoff, Fujimori won with just over 51% of the vote. While votes

for Toledo declined from 40.24% of the valid votes cast in the first

round to 25.67% of the valid votes in the second round, invalid votes

jumped from 2.25% of the total votes cast in the first round to 29.93%

of total votes in the second round. The large percentage of votes cast

as invalid suggested that many Peruvians took Toledo's advice to spoil

their ballots. Although

Fujimori had won the runoff with only a bare majority, rumors of

irregularities led to daily demonstrations in front of the presidential

palace. As a conciliatory measure, Fujimori appointed former opposition

candidate Federico Salas as the new prime minister. However, opposition

parties in Parliament refused to support this move while Toledo

campaigned vigorously to have the election annulled. At this point, a

corruption scandal involving Vladimiro Montesinos, de-facto chief of Peru's National Intelligence Service (SIN) who had connections with the CIA, broke out. The scandal exploded into full force on the evening of September 14, 2000, when the cable television station Canal N broadcast footage of Montesinos apparently bribing opposition congressman Alberto Kouri for his defection to Fujimori's Perú 2000 party. This video was presented by Fernando Olivera,

leader of the FIM (Independent Moralizing Front), who purchased it from

one of Montesinos's closest allies (nicknamed by the Peruvian press El Patriota). Fujimori's

support virtually collapsed, and on November 10, Fujimori won approval

from Congress to hold elections on April 8, 2001 — in which he would not

be a candidate. On November 13, Fujimori left Peru for a visit to Brunei to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum. On November 16, Valentín Paniagua took

over as president of Congress after the pro-Fujimori leadership lost a

vote of confidence. On November 17, Fujimori traveled from Brunei to Tokyo, where he submitted his presidential resignation via

fax. Congress refused to accept his resignation, instead voting 62–9 to

remove Fujimori from office on the grounds that he was "morally

disabled." On

November 19, government ministers presented their resignations en bloc.

Because Fujimori's first vice president, Francisco Tudela, had broken

with Fujimori and resigned a few days earlier, his successor Ricardo

Márquez came to claim the presidency. Congress, however, refused

to recognize him, as he was an ardent Fujimori loyalist; Márquez

resigned two days later. Paniagua was next in line, and became interim

president to oversee the April elections.

When Fujimori came to power, much of Peru was dominated by the Maoist insurgent group Sendero Luminoso ("Shining Path"), and the Marxist-Leninist group Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA).

In 1989, 25% of Peru's district and provincial councils opted not to

hold elections, owing to a persistent campaign of assassination, over

the course of which over 100 officials had been killed by Shining Path

in that year alone. That same year, over one-third of Peru's positions for justices of the peace stood vacant, owing to Shining Path intimidation. Union leaders and military officials had also been assassinated throughout the 1980s. By

the early 1990s, some parts of the country were under the control of

the insurgents, in territories known as "zonas liberadas" ("liberated

zones"), where inhabitants lived under the rule of these groups and

paid them taxes. When

Shining Path arrived in Lima, it organized "paros armados" ("work

stoppages"), which were enforced by killings and other forms of

violence. The leadership of Shining Path was largely university

students and teachers. Two previous governments, those of Fernando Belaúnde Terry and Alan García,

at first neglected the threat posed by Shining Path, then launched an

unsuccessful military campaign to eradicate it, undermining public

faith in the state and precipitating an exodus of elites. By 1992, Shining Path guerrilla attacks had claimed an estimated 20,000 lives over the course of 12 years. The July 16, 1992 Tarata Bombing,

in which several car bombs exploded in Lima's wealthiest district,

killed over 40 people; the bombings were characterized by one

commentator as an "offensive to challenge President Alberto Fujimori." The

bombing at Tarata was followed up with a "weeklong wave of car bombings

... Bombs hit banks, hotels, schools, restaurants, police stations and

shops ... [G]uerrillas bombed two rail bridges from the Andes, cutting off some of Peru's largest copper mines from coastal ports." Fujimori

has been credited by many Peruvians with ending the fifteen-year reign

of terror of Shining Path. As part of his anti-insurgency efforts,

Fujimori granted the military broad powers to arrest suspected

insurgents and try them in secret military courts with few legal

rights. This measure has often been criticized for having compromised

the fundamental democratic and human right of an open trial wherein the

accused faces the accuser. Fujimori contended that these measures were

justified, that this compromise of open trials was necessary because

the judiciary was too afraid to charge alleged insurgents, and that

judges and prosecutors had legitimate fears of insurgent reprisals

against them or their families. At

the same time, Fujimori's government armed rural Peruvians, organizing

them into groups known as "rondas campesinas" ("peasant patrols"). Insurgent activity was in decline by the end of 1992, and

Fujimori took credit for this development, claiming that his campaign

had largely eliminated the insurgent threat. After the 1992 auto-coup,

the intelligence work of the DINCOTE (National

Counter-Terrorism Directorate) led to the capture of the leaders from

Shining Path and MRTA, including notorious Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán.

Guzmán's capture was a political coup for Fujimori, who used it

to great effect in the press; in an interview with documentarian Ellen Perry,

Fujimori even notes that he specially ordered Guzmán's prison

jumpsuit to be white with black stripes, to enhance the image of his

capture in the media. Critics charge that to achieve the defeat of Shining Path, the Peruvian military engaged in widespread human rights abuses,

and that the majority of the victims were poor highland countryside

inhabitants caught in the crossfire between the military and

insurgents. The final report of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission,

published on 28 August 2003, revealed that while the majority of the

atrocities committed between 1980 and 1995 were the work of Shining

Path, the Peruvian armed forces were also guilty of having destroyed

villages and murdered countryside inhabitants whom they suspected of

supporting insurgents. The Japanese embassy hostage crisis began on December 17, 1996, when fourteen MRTA militants

seized the residence of the Japanese ambassador in Lima during a party,

taking hostage some four hundred diplomats, government officials, and

other dignitaries. The action was partly in protest of prison

conditions in Peru. During the four-month standoff, the Emerretistas gradually

freed all but 72 of their hostages. The government rejected the

militants' demand to release imprisoned MRTA members and secretly

prepared an elaborate plan to storm the residence, while stalling by

negotiating with the hostage-takers. On April 22, 1997, a team of military commandos, codenamed "Chavín de Huantar", raided the building. One hostage, two military commandos, and all 14 MRTA insurgents were killed in the operation. Images

of President Fujimori at the ambassador's residence during and after

the military operation, surrounded by soldiers and liberated

dignitaries, and walking among the corpses of the insurgents, were

widely televised. The conclusion of the four-month long standoff was

used by Fujimori and his supporters to bolster his image as tough on

terrorism. Several organizations criticized Fujimori's methods in the struggle against Shining Path and the MRTA. According to Amnesty International,

"the widespread and systematic nature of human rights violations

committed during the government of former head of state Alberto

Fujimori (1990–2000) in Peru constitute crimes against humanity under

international law." Fujimori's alleged association with death squads is currently being studied by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, after the court accepted the case of "Cantuta vs Perú". The 1991 Barrios Altos massacre by members of the death squad Grupo Colina, made up of members of the Peruvian Armed Forces, was one of the crimes cited in the request for his extradition submitted by the Peruvian government to Japan in 2003. From 1996 to 2000, the Fujimori government oversaw a massive family planning campaign known as Voluntary Surgical Contraception. The United Nations, USAID and other international aid agencies supported this campaign. The Nippon Foundation, headed by Ayako Sono, a Japanese novelist and personal friend of Fujimori, supported as well. Nearly 300,000, mostly indigenous, women were coercively or forcefully sterilized during these years. The success of the operation in the Japanese embassy hostage crisis was

tainted by subsequent allegations that at least three and possibly

eight of the insurgents had been summarily executed by the commandos

after surrendering. In 2002, the case was taken up by public

prosecutors, but the Peruvian Supreme Court ruled that the military

tribunals had jurisdiction. A military court later absolved them of

guilt, and the "Chavín de Huantar" soldiers led the 2004

military parade. In response, in 2003 MRTA family members lodged a

complaint with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR)

accusing the Peruvian state of human rights violations, namely that the

MRTA insurgents had been denied the "right to life, the right to

judicial guarantees and the right to judicial protection". The IACHR

accepted the case and is currently studying it. Peruvian

Minister of Justice Maria Zavala has stated that this verdict by the

IACHR supports the Peruvian government's extradition of Fujimori from

Chile. Though the IACHR verdict does not directly implicate Fujimori,

it does fault the Peruvian government for its complicity in the 1992 Cantuta University killings. After

his faxed resignation was rejected by the Congress, Fujimori was

relieved of his duties as president and banned from Peruvian politics

for a decade. He remained in self-imposed exile in Japan, where he resided with his friend, the famous Catholic novelist Ayako Sono. Several senior Japanese politicians have supported Fujimori, partly for his decisive action in ending the 1997 Japanese embassy crisis. Alejandro Toledo,

who assumed the presidency in 2001, spearheaded the criminal case

against Fujimori. He arranged meetings with the Supreme Court, tax

authorities, and other powers in Peru in order to "coordinate the joint

efforts to bring the criminal Fujimori from Japan." His vehemence in

this matter at times compromised Peruvian law: forcing the judiciary

and legislative system to keep guilty sentences without hearing

Fujimori's defense; not providing Fujimori with a lawyer in absence of

representation; and expelling pro-Fujimori congressmen from the

parliament without proof of the accusations against them. The latter

action was later reversed by the judiciary. The

Toledo administration's review of the Fujimori administration led to

the Peruvian Congress authorizing charges against Fujimori, in August

2001. Fujimori was alleged to be a co-author, alongside Vladimiro

Montesinos, in the death-squad killings at Barrios Altos in 1991 and La Cantuta in 1992. At the behest of Peruvian authorities, Interpol issued an arrest order for Fujimori on charges that included murder, kidnapping, and crimes against humanity.

Meanwhile, the Peruvian government found that Japan was not amenable to

the extradition of Fujimori; a protracted diplomatic debate ensued,

when Japan showed itself unwilling to accede to the extradition request. In

September 2003, Congresswoman Dora Núñez Dávila,

joined by Minister of Health Luis Soari, denounced Fujimori and several

of his ministers for crimes against humanity, for allegedly having

overseen forced sterilizations during

his regime. In November, Congress approved charges against Fujimori, to

investigate how much he had been involved in the airdrop of Kalashnikov rifles into the Colombian jungle in 1999 and 2000 for guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Fujimori maintains he had no knowledge of the arms-trading, and blames

Montesinos. By approving the charges, Congress lifted the immunity

granted to Fujimori as a former president, so that he can be criminally

charged and prosecuted. Congress

also voted to support charges against Fujimori for the detention and

disappearance of 67 students from the central Andean city of Huancayo, and the disappearance of several residents from the northern coastal town of Chimbote during

the 1990s. It also approved charges that Fujimori mismanaged millions

of dollars from Japanese charities, suggesting that the millions of

dollars in his bank account were far too much to have been accumulated

legally. By

March 2005, it appeared that Peru had all but abandoned its efforts to

extradite Fujimori from Japan. In September of that year, Fujimori

obtained a new Peruvian passport in Tokyo, and announced his intention

to run in the Peruvian national election, 2006. The

Special Prosecutor established to investigate Fujimori released a

report alleging that the Fujimori administration had grafted US$2

billion. Most of this money is related to Vladimiro Montesinos' web of corruption. The Special Prosecutor's figure of two billion dollars is considerably higher than that arrived at by Transparency International,

an NGO that studies corruption. In its "Global Corruption Report 2004",

Transparency International listed Fujimori as leading the seventh most

corrupt government of the past two decades, estimating that the

corruption may have embezzled USD $600 million in funds. Undaunted

by the judicial proceedings underway against him, which, citing

Toledo's involvement, he dismissed as "politically motivated",

Fujimori, working from Japan, established a new political party in Peru, Sí Cumple, in hopes of participating in the 2006 presidential elections.

In February 2004 the Constitutional Court dismissed the possibility of

Fujimori participating in those elections, noting that the ex-president

was barred by Congress from holding office for ten years. The decision

was regarded as unconstitutional by Fujimori supporters such as

ex-congress members Luz Salgado, Marta Chávez, and Fernán

Altuve, who argued it was a "political" maneuver, and that the only

body with authority to determine the matter is the Jurado Nacional de

Elecciones (JNE). Valentín Paniagua disagreed, suggesting that

the Constitutional Court finding is binding, and that "no further

debate is possible". Fujimori's Sí Cumple (roughly translated, "He Keeps His Word") received more than 10% in many country-level polls, contending with APRA for the second place slot. On April 7, 2009, a three-judge panel convicted Fujimori on charges of human rights abuses, declaring that the "charges against him have been proven beyond all reasonable doubt". The panel found him guilty of ordering the Grupo Colina death squad to execute the November 1991 Barrios Altos massacre and the July 1992 La Cantuta Massacre, which resulted in the deaths of 25 people, and for taking part in the kidnappings of Peruvian journalist of opposition Gustavo Gorriti and businessman Samuel Dyer. Fujimori's

conviction is the only instance of a democratically elected head of

state being tried and convicted of human rights abuses in his own

country. Later on April 7, the court sentenced Fujimori to 25 years in prison. He faced a third trial in July 2009 over allegations that he illegally gave $15 million in state funds to Vladimiro Montesinos, former head of the National Intelligence Service, during the two months prior to his fall from power. Fujimori admitted paying the money to Montesinos but claimed that he had later paid back the money to the state. The court found him guilty of embezzlement and sentenced him to a further seven and a half years in prison. A fourth, and apparently final, trial took place in September 2009 in Lima. Fujimori

was accused of using Montesinos to bribe and tap the phones of

journalists, businessmen and opposition politicians – evidence of which

led to the collapse of his government in 2000. Fujimori admitted the charges but claimed that the charges were made to damage his daughter's presidential election campaign. The

prosecution asked the court to sentence Fujimori to eight years

imprisonment with a fine of $1.6 million plus $1 million in

compensation to ten people whose phones were bugged. Fujimori pled guilty and was sentenced to six years' imprisonment on 30 September 2009.