<Back to Index>

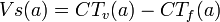

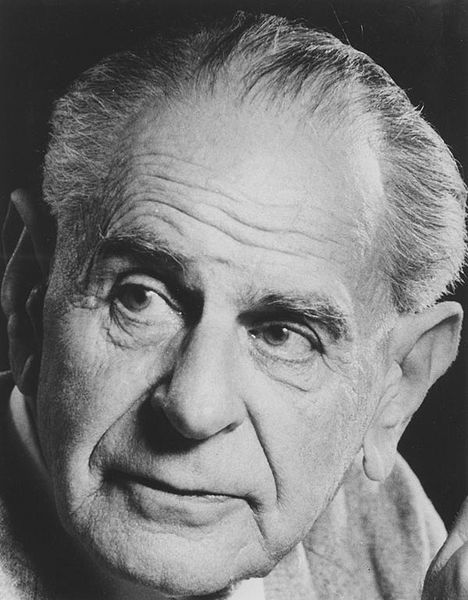

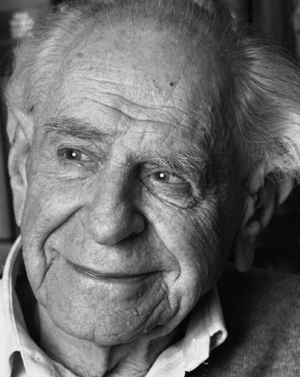

- Philosopher Karl Raimund Popper, 1902

- Author Helen Beatrix Potter, 1866

- President of Peru Alberto Ken'ya Fujimori Fujimori, 1938

Sir Karl Raimund Popper, CH, FRS, FBA (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian and British philosopher and a professor at the London School of Economics. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of science of the 20th century; he also wrote extensively on social and political philosophy. Popper is known for his attempt to repudiate the classical observationalist/inductivist account of scientific method by advancing empirical falsification instead, for his opposition to the classical justificationist account of knowledge which he replaced with critical rationalism, "the first non justificational philosophy of criticism in the history of philosophy", and for his vigorous defense of liberal democracy and the principles of social criticism that he came to believe made a flourishing "open society" possible.

Karl Popper was born in Vienna (then in Austria-Hungary) in 1902, to middle-class parents of assimilated Jewish origins, both of whom had converted to Christianity. Karl's father Dr Simon Siegmund Carl Popper was a lawyer from Prague, and mother Jenny Schiff was of Silesian and Hungarian descent. Popper received a Lutheran upbringing and was educated at the University of Vienna. His father was a doctor of law at the Vienna University and a bibliophile who had 12,000 – 14,000 volumes in his personal library. Popper inherited from him both the library and the disposition. In 1919, Popper became attracted by Marxism and subsequently joined the Association of Socialist School Students. He also became a member of the Social Democratic Party of Austria, which was at that time a party that fully adopted the Marxist ideology. He soon became disillusioned by the philosophical restraints imposed by the historical materialism of Marx, abandoned the ideology and remained a supporter of social liberalism throughout his life.

In

1928, he earned a doctorate in Philosophy, and then from 1930 to 1936

taught secondary school. Popper published his first book, Logik der Forschung (The Logic of Scientific Discovery), in 1934. Here, he criticised psychologism, naturalism, inductionism, and logical positivism, and put forth his theory of potential falsifiability as the criterion demarcating science from non-science. In 1937, the rise of Nazism and the threat of the Anschluss led Popper to emigrate to New Zealand, where he became lecturer in philosophy at Canterbury University College New Zealand (at Christchurch). In 1946, he moved to England to become reader in logic and scientific method at the London School of Economics.

Three years later, he was appointed as professor of logic and

scientific method at the University of London in 1949. Popper was

president of the Aristotelian Society from 1958 to 1959. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1965, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in

1976. He retired from academic life in 1969, though he remained

intellectually active for the rest of his life. He was invested with

the Insignia of a Companion of Honour in 1982. Popper was a member of the Academy of Humanism and described himself as an agnostic, showing respect for the moral teachings of Judaism and Christianity. Popper won many awards and honours in his field, including the Lippincott Award of the American Political Science Association, the Sonning Prize, and fellowships in the Royal Society, British Academy, London School of Economics, King's College London, Darwin College Cambridge, and Charles University, Prague. Austria awarded him the Grand Decoration for Services to the Republic of Austria in Gold. Popper died in Croydon, UK at the age of 92 on 17 September 1994. After cremation, his ashes were taken to Vienna and buried at Lainzer cemetery adjacent to the ORF Centre, where his wife Josefine Anna Henninger, who had died in Austria several years before, had already been buried. Popper coined the term critical rationalism to describe his philosophy. The term indicates his rejection of classical empiricism, and of the classical observationalist-inductivist account of science that had grown out of it. Popper argued strongly against the latter, holding that scientific theories are

abstract in nature, and can be tested only indirectly, by reference to

their implications. He also held that scientific theory, and human

knowledge generally, is irreducibly conjectural or hypothetical, and is

generated by the creative imagination in order to solve problems that

have arisen in specific historico-cultural settings. Logically, no

number of positive outcomes at the level of experimental testing can

confirm a scientific theory, but a single counterexample is logically

decisive: it shows the theory, from which the implication is derived,

to be false. The term "falsifiable" does not mean something is false;

rather, that if it is false, then this can be shown by observation or

experiment. Popper's account of the logical asymmetry between verification and falsifiability lies at the heart of his philosophy of science. It also inspired him to take falsifiability as his criterion of demarcation between

what is and is not genuinely scientific: a theory should be considered

scientific if and only if it is falsifiable. This led him to attack the

claims of both psychoanalysis and contemporary Marxism to

scientific status, on the basis that the theories enshrined by them are

not falsifiable. Popper also wrote extensively against the famous Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. He strongly disagreed with Niels Bohr's instrumentalism and supported Albert Einstein's realist approach to scientific theories about the universe. Popper's falsifiability resembles Charles Peirce's fallibilism. In Of Clocks and Clouds (1966), Popper remarked that he wished he had known of Peirce's work earlier. In All Life is Problem Solving,

Popper sought to explain the apparent progress of scientific

knowledge — how it is that our understanding of the universe seems to

improve over time. This problem arises from his position that the truth

content of our theories, even the best of them, cannot be verified by

scientific testing, but can only be falsified (again, in this context

the word 'falsified' does not refer to something being 'fake'; rather,

that something can be shown to be false by observation or experiment).

If so, then how is it that the growth of science appears to result in a

growth in knowledge? In Popper's view, the advance of scientific

knowledge is an evolutionary process characterised by his formula: In response to a given problem situation (PS1), a number of competing conjectures, or tentative theories (TT), are systematically subjected to the most rigorous attempts at falsification possible. This process, error elimination (EE), performs a similar function for science that natural selection performs for biological evolution.

Theories that better survive the process of refutation are not more

true, but rather, more "fit" — in other words, more applicable to the

problem situation at hand (PS1).

Consequently, just as a species' "biological fit" does not predict

continued survival, neither does rigorous testing protect a scientific

theory from refutation in the future. Yet, as it appears that the

engine of biological evolution has produced, over time, adaptive traits

equipped to deal with more and more complex problems of survival,

likewise, the evolution of theories through the scientific method may,

in Popper's view, reflect a certain type of progress: toward more and

more interesting problems (PS2).

For Popper, it is in the interplay between the tentative theories

(conjectures) and error elimination (refutation) that scientific

knowledge advances toward greater and greater problems; in a process

very much akin to the interplay between genetic variation and natural

selection. Where does "truth" fit into all this? As early as 1934 Popper wrote of the search for truth as "one of the strongest motives for scientific discovery." Still, he describes in Objective Knowledge (1972) early concerns about the much-criticised notion of truth as correspondence. Then came the semantic theory of truth formulated by the logician Alfred Tarski and published in 1933. Popper writes of learning in 1935 of the consequences of Tarski's theory, to his intense joy. The theory met critical objections to truth as correspondence and thereby rehabilitated it. The theory also seemed, in Popper's eyes, to support metaphysical realism and the regulative idea of a search for truth. According to this theory, the conditions for the truth of a sentence as well as the sentences themselves are part of a metalanguage.

So, for example, the sentence "Snow is white" is true if and only if

snow is white. Although many philosophers have interpreted, and

continue to interpret, Tarski's theory as a deflationary theory, Popper refers to it as a theory in which "is true" is replaced with "corresponds to the facts." He bases this interpretation on the fact that examples such as the one described above refer to two things: assertions and the facts to

which they refer. He identifies Tarski's formulation of the truth

conditions of sentences as the introduction of a "metalinguistic

predicate" and distinguishes the following cases: The

first case belongs to the metalanguage whereas the second is more

likely to belong to the object language. Hence, "it is true that"

possesses the logical status of a redundancy. "Is true", on the other

hand, is a predicate necessary for making general observations such as

"John was telling the truth about Phillip." Upon

this basis, along with that of the logical content of assertions (where

logical content is inversely proportional to probability), Popper went

on to develop his important notion of verisimilitude or "truthlikeness". The

intuitive idea behind verisimilitude is that the assertions or

hypotheses of scientific theories can be objectively measured with

respect to the amount of truth and falsity that they imply. And, in

this way, one theory can be evaluated as more or less true than another

on a quantitative basis which, Popper emphasizes forcefully, has

nothing to do with "subjective probabilities" or other merely

"epistemic" considerations. The simplest mathematical formulation that Popper gives of this concept can be found in the tenth chapter of Conjectures and Refutations. Here he defines it as: where Vs(a) is the verisimilitude of a, CTv(a) is a measure of the content of truth of a, and CTf(a) is a measure of the content of the falsity of a. Knowledge, for Popper, was objective,

both in the sense that it is objectively true (or truthlike), and also

in the sense that knowledge has an ontological status (i.e., knowledge

as object) independent of the knowing subject (Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, 1972). He proposed three worlds (Popperian cosmology):

World One, being the physical world, or physical states; World Two,

being the world of mind, or mental states, ideas, and perceptions; and

World Three, being the body of human knowledge expressed in its

manifold forms, or the products of the second world made manifest in

the materials of the first world (i.e.– books, papers, paintings,

symphonies, and all the products of the human mind). World Three, he

argued, was the product of individual human beings in exactly the same

sense that an animal path is the product of individual animals, and

that, as such, has an existence and evolution independent of any

individual knowing subjects. The influence of World Three, in his view,

on the individual human mind (World Two) is at least as strong as the

influence of World One. In other words, the knowledge held by a given

individual mind owes at least as much to the total accumulated wealth

of human knowledge, made manifest, as to the world of direct

experience. As such, the growth of human knowledge could be said to be

a function of the independent evolution of World Three. Many

contemporary philosophers have not embraced Popper's Three World

conjecture, due mostly, it seems, to its resemblance to Cartesian dualism. In The Open Society and Its Enemies and The Poverty of Historicism, Popper developed a critique of historicism and

a defence of the 'Open Society'. Popper considered historicism to be

the theory that history develops inexorably and necessarily according

to knowable general laws towards a determinate end. He argued that this

view is the principal theoretical presupposition underpinning most

forms of authoritarianism and totalitarianism.

He argued that historicism is founded upon mistaken assumptions

regarding the nature of scientific law and prediction. Since the growth

of human knowledge is a causal factor in the evolution of human

history, and since "no society can predict, scientifically, its own

future states of knowledge", it follows, he argued, that there can be

no predictive science of human history. For Popper, metaphysical and

historical indeterminism go hand in hand. In

a 1992 lecture, Popper explained the connection between his political

philosophy and his philosophy of science. As he stated, he was in his

early years impressed by communism and also active in the Austrian

Communist party. What had a profound effect on him was an event that

happened in 1918: during a riot, caused by the Communists, the police

shot several people, including some of Popper's friends. When Popper

later told the leaders of the Communist party about this, they

responded by stating that this loss of life was necessary in working

towards the inevitable workers' revolution. This statement did not

convince Popper and he started to think about what kind of reasoning

would justify such a statement. He later concluded that there could not

be any justification for it, and this was the start of his later

criticism of historicism. In 1947, Popper founded with Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises and others the Mont Pelerin Society to defend classical liberalism, in the spirit of Open society. Among his contributions to philosophy is his attempt to answer the philosophical problem of induction as emphasized strongly by David Hume.

The problem, in basic terms, can be understood by example: given that

the sun has risen every day for as long as anyone can remember, what is

the rational proof that it will rise tomorrow? How can one rationally

prove that past events will continue to repeat in the future, just

because they have repeated in the past? Popper

claims to have found a solution to the problem of induction. His reply

is characteristic, and ties in with his criterion of falsifiability. He

states that while there is no way to prove that the sun will rise, it

is possible to formulate the theory that every day the sun will rise — if

it does not rise on some particular day, the theory will be falsified

and will have to be replaced by a different one. Until that day, there

is no need to reject the assumption that the theory is true. Neither is

it rational according to Popper to instead make the more complex

assumption that the sun has risen until a given day, but will stop so

doing the next day, or similar statements with additional conditions. Such

a theory would be true with higher probability, because it cannot be

attacked so easily: To falsify the first one, it is sufficient to find

that sun has stopped rising; to falsify the second one, one

additionally needs the assumption that the given day has not yet been

reached. Popper held that it is the least likely, or most easily

falsifiable, or simplest theory (attributes which he all identified as

the same thing) that explains known facts that one should rationally

prefer. His opposition to positivism, which held that it is the theory

most likely to be true that one should prefer, here becomes very

apparent. It is impossible, Popper argues, to ensure a theory to be

true (but not fatal, since even false theories may have true

consequence); it is more important that they can be eliminated and

corrected as easily as possible if false. Popper and Hume agreed

that there is often a psychological belief that the sun will rise

tomorrow, but both denied that there is logical justification for the

supposition that it will, simply because it always has in the past. To Popper, who was an anti-justificationist, traditional philosophy is misled by the false principle of sufficient reason.

He thinks that no assumption can ever be or needs ever to be justified,

so a lack of justification is not a justification for doubt. Instead,

theories should be tested and scrutinized. It is not the goal to bless

theories with claims of certainty or justification, but to eliminate

errors in them. Popper and John Eccles speculated on the problem of free will for many years, generally agreeing on an interactionist dualist theory of mind as a separate physical substance. When he gave the first Arthur Holly Compton Memorial Lecture in 1955, Popper revisited the idea of quantum indeterminacy as

a source of human freedom. Eccles had suggested that "critically poised

neurons" might be influenced by the mind to assist in a decision.

Popper criticized Compton's idea of amplified quantum events affecting

the decision. Popper called not for something between chance

and necessity but for a combination of randomness and control to

explain freedom, though not yet explicitly in two stages with random

chance before the controlled decision. "freedom

is not just chance but, rather, the result of a subtle interplay

between something almost random or haphazard, and something like a

restrictive or selective control." Then in his 1977 book with John Eccles, The Self and its Brain,

Popper finally formulates the two-stage model in a temporal sequence.

And he compares free will to Darwinian evolution and natural selection.

Other thinkers who have formulated a two-stage model for free will

include William James, Henri Poincaré, Compton, Henry Margenau, and Daniel Dennett.

.

.