<Back to Index>

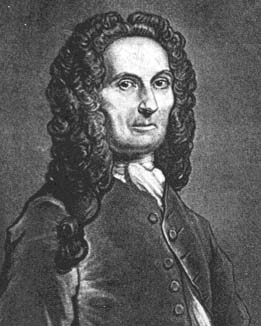

- Mathematician Abraham de Moivre, 1667

- Photographer Dorothea Lange, 1895

- General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party János Kádár, 1912

Abraham de Moivre (26 May 1667, Vitry-le-François, Champagne, France – 27 November 1754, London, England) was a French mathematician famous for de Moivre's formula, which links complex numbers and trigonometry, and for his work on the normal distribution and probability theory. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1697, and was a friend of Isaac Newton, Edmund Halley, and James Stirling. Among his fellow Huguenot exiles in England, he was a colleague of the editor and translator Pierre des Maizeaux.

The social status of the family of de Moivre is unclear, but his father, a surgeon, was able to send him to the Protestant academy at Sedan (1678–82). De Moivre studied logic at the Academy of Saumur (1682–84), attended the Collège d'Harcourt in Paris (1684), and studied privately with Jacques Ozanam (1684–85). It appears that de Moivre never received a college degree. A Calvinist, de Moivre left France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) and spent the remainder of his life in England. Throughout his life de Moivre remained poor. It is reported that he was a regular customer of Slaughter's Coffee House, St. Martin's Lane at Cranbourn Street, where he earned a little money from playing chess. Abraham de Moivre died in London and was buried at St Martin-in-the-Fields, although his body was later moved.

De Moivre wrote a book on probability theory, The Doctrine of Chances,

said to have been prized by gamblers. It is reported in all seriousness

that de Moivre correctly predicted the day of his own death. Noting

that he was sleeping 15 minutes longer each day, De Moivre surmised

that he would die on the day he would sleep for 24 hours. A simple

mathematical calculation quickly yielded the date, 27 November 1754. He

did indeed die on that day. De Moivre first discovered Binet's formula, the closed-form expression for Fibonacci numbers linking the nth power of φ to the nth Fibonacci number. Abraham

de Moivre was born in Vitry in Champagne on May 26, 1667. His father,

Daniel de Moivre, was a surgeon and, although middle class, he believed

in the value of education. Although his parents were Protestant, he

first attended the Catholic school of the Christian Brothers in Vitry

which was unusually tolerant given the religious tensions in France at

the time. When he was eleven, his parents sent him to the Protestant

Academy at Sedan, where he spent four years studying Greek under Jacques du Rondel.

The Protestant Academy at Sedan had been founded in 1579 at the

initiative of Françoise de Bourbon, widow of Henri-Robert de la

Marck; in 1682 the Protestant Academy at Sedan was suppressed and de

Moivre enrolled to study logic at Saumur for two years. Although

mathematics was not part of his course work, de Moivre read several

mathematical works on his own including Elements de mathematiques by

Father Prestet and a short treatise on games of chance, De Ratiociniis

in Ludo Aleae, by Christiaan Huygens. In 1684 he moved to Paris to

study physics and for the first time had formal mathematics training

with private lessons from Jacques Ozanam. Religious persecution in France became severe when King Louis XIV passed the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 which revoked the Edict of Nantes,

that had given substantial rights to French Protestants. It forbade

Protestant worship and required all children to be baptized by Catholic

priests. De Moivre was sent to the Prieure de Saint-Martin, a school to

which Protestant children were sent by the authorities for

indoctrination into Catholicism. It is unclear when de Moivre left the

Prieure de Saint-Martin and moved to England as the records of the

Prieure de Saint-Martin indicate that he left the school in 1688 but de

Moivre and his brother presented themselves as Huguenots to be admitted

to the Savoy Church in London on August 28, 1687. By

the time he arrived in London, de Moivre was a competent mathematician

with a good knowledge of many of the standard texts. In order to obtain

a living, de Moivre became a private tutor of mathematics, visiting his

pupils or teaching in the coffee houses of London. De Moivre continued

his studies of mathematics after visiting the Earl of Devonshire and seeing Newton’s recent book, Principia.

After looking through the book he immediately realized that the book

was far deeper than those which he had studied and he was determined to

read and understand it. However, he was required to take extended walks

around London to travel between his tutees, de Moivre had little time

for study so he would tear pages from the book and carry them around in

his pocket to read in the times between lessons. Eventually de Moivre

became so knowledgeable about the material that Newton would refer

questions to him saying, “Go to Mr. de Moivre; he knows these things

better than I do.” By 1692, de Moivre became friends with Edmond Halley and soon after Isaac Newton himself.

In 1695, Halley communicated de Moivre’s first mathematics paper, which

arose from his study of fluxions in the Principia, to the Royal Society.

This paper was published in the Philosophical Transactions that same

year. Shortly after publishing this paper de Moivre also generalized

Newton’s famous Binomial Theorem into the Multinomial Theorem. The Royal Society became

apprised of this method in 1697 and made de Moivre a member two months

later. After

being accepted, Halley encouraged de Moivre to turn his attention to

astronomy. In 1705, Mr. De Moivre discovered, intuitively, that “the

centripetal force of any planet is directly related to its distance

from the centre of the forces and reciprocally related to the product

of the diameter of the evolute and the cube of the perpendicular on the

tangent”. Johann Bernoulli proved this result in 1710. Despite

these successes, de Moivre was unable to obtain an appointment to a

Chair of Mathematics at a university which would release him from his

dependence on time-consuming tutoring that burdened his life to a

greater extent than it did most other mathematicians of the time. At

least a part of the reason was a bias against his French origins. In 1712, de Moivre was appointed to a commission set up by the Royal Society alongside,

MM. Arbuthnot, Hill, Halley, Jones, Machin, Burnet, Robarts, Bonet,

Aston, and Taylor to review the claims of Newton and Leibniz as to who

discovered calculus.

De

Moivre continued studying the fields of probability and mathematics

until his death in 1754 and several additional papers were published

after his death.