<Back to Index>

- Physicist Niels Henrik David Bohr, 1885

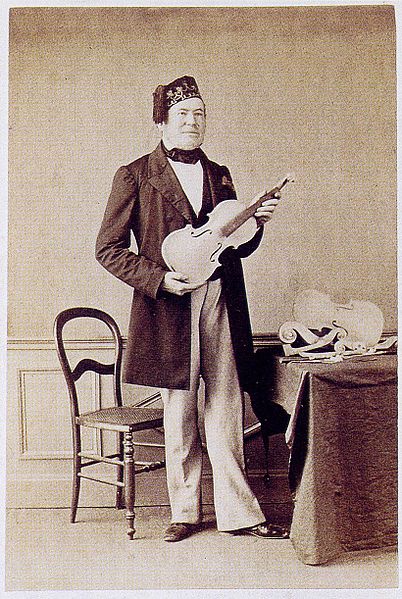

- Violin Maker Jean Baptiste Vuillaume, 1798

- President of Peru Fernando Belaúnde Terry, 1912

Jean Baptiste Vuillaume (October 7, 1798 – March 19, 1875) was an illustrious French violin maker. He made over 3,000 instruments and was also a fine businessman and an inventor.

| “ | What set him apart from the rest is that he was not only an artist without equal, but also a tireless seeker of perfection to whom there was no such thing as failure. It was this driving force which shone through his life and made his work immortal. | ” |

—Roger Millant, Paris 1972. | ||

| “ | Together with Nicolas Lupot, Vuillaume is the foremost French stringed instrument maker and the most important of the Vuillaume family of luthiers | ” |

—E. Jaeger, curator of the Vuillaume exhibit in Cite de la Musique. | ||

Born to a Mirecourt family since both his grandfather and his father were engaged in the same trade, Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume arrived in Paris in 1818 to work for François Chanot. In 1821, he joined the workshop of Simon Lété, François-Louis Pique's son-in-law, Rue Pavée St. Sauveur. He became his partner and in 1825 settled in the Rue Croix des Petits-Champs under the name of "Lété et Vuillaume". His first labels are dated 1823.

Beginning in 1827, at the height of the Neo-Gothic period

when many artists were drawing their inspiration from 15th and 16th

century cathedrals and monuments, and in order to satisfy the demand of virtuosi and

amateurs for great 18th century Italian violin makers, he started to

imitate old instruments. Some copies were so perfect that, at that

time, it was difficult even for a discerning eye to tell the difference. In

1827, he won a silver medal at the Paris Universal Exhibition.

The

following year, in 1828, he set his own business at 46 Rue des

Petits-Champs and began creating his own models. His

workshop then became the most important in the capital. Within barely

twenty years, it became the leading workshop in Europe. A major factor

in his success was doubtless his purchase of 144 instruments made by

the most celebrated Italian masters, including 24 Stradivari and the

famous Messiah Stradivarius presently kept at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford University, from the heirs of an Italian tradesman named Luigi Tarisio, for 80,000 francs in 1855. In

1858, in order to avoid paying the capital's custom-duties on his wood

imports, he settled Rue Pierre Demours, near the Ternes, which were at

that time outside Paris. He

was then at the height of his reputation, having won various gold

medals in the Competitions of the popular Paris Universal Exhibitions

in 1839, 1844 and 1855, the Council Medal in London in 1851 and, in

that same year, the Legion of Honour. His third period, the Golden

Period, continued until his death. A

maker of more than 3,000 instruments - almost all of which are numbered

- and a fine tradesman, Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume was also a gifted

inventor as is demonstrated by his research in collaboration with the

acoustics expert Savart. As an innovator, he developed many new

instruments and mechanisms, most notably a large viola which he called a "contralto", and the three-string Octobass (1849–51), a huge double bass standing 3·65 metres high. He also created the hollow steel bow (particularly

appreciated by Charles de Bériot, among others), and the

‘self-rehairing’ bow. For the latter, the hair purchased in prepared

hanks, could be inserted by the player in the time it takes to change a

string, and was tightened or loosened by a simple mechanism inside the

frog. The frog itself was fixed to the stick, and the balance of the

bow thus remained constant when the hair stretched with use. He

also designed a round-edged frog mounted to the butt by means of a

recessed track, which he encouraged his bowmakers to use; other details

of craft, however, make it possible to identify the actual maker of

many Vuillaume bows. The bows are stamped, often rather faintly, either

vuillaume à paris or j.b. vuillaume. Other innovations include the insertion of Stanhopes in

the eye of the frogs of his bows, a kind of mute (the "pédale

sourdine") and several machines, including one for manufacturing gut

strings of perfectly equal thickness. Most Great Bow Makers of the 19th century collaborated with his workshop including Jean Pierre Marie Persois, Jean Adam / bow maker, Dominique Peccatte, Nicolas Remy Maire, François Peccatte, Nicolas Maline, Pierre Simon, François Nicolas Voirin, Charles Peccatte, Charles Claude Husson, Joseph Fonclause and Jean Joseph Martin are among the most celebrated. Jean-Baptiste

Vuillaume was an innovative violin maker and restorer, and a tradesman

who traveled all of Europe in search of instruments. Due to this fact,

most instruments by the great Italian violin makers passed through his

workshop. Vuillaume then made accurate measurements of their dimensions

and made copies of them. He drew his inspiration from two violin makers: Antonio Stradivari, his favorite violin being the "Le Messie" (Messiah), and Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù and the "Cannone" which belonged to Niccolò Paganini; others such as Maggini, Da Salò and Nicolò Amati were also imitated, but to a lesser extent. Tarisio

never parted with the violin and not until his death in 1854 had anyone

outside Italy seen it. In 1855, Vuillaume was able to acquire it, and

it remained with him, also until his death. Vuillaume guarded the

'Messiah' jealously, keeping it in a glass case and allowing no one to

examine it. However, he did allow it to be shown at the 1872 Exhibition

of Instruments in the South Kensington Museum, and this was its first

appearance in England. After Vuillaume's death in 1875, the violin

became the property of his two daughters and then of his son-in-law,

the violinist Alard. After Alard's death in 1888, his heirs sold the

'Messiah' in 1890 to W.E. Hill and Sons on behalf of a Mr. R. Crawford

of Edinburgh for 2,600 British pounds, at that time the largest sum

ever paid for a violin. —David D. Boyden, London 1969 Vuillaume made numerous copies of his favorite violin ‘Le Messie’, the more noteworthy among them being: This

was the foundation of his success, for the modern copies found a ready

sale, and orders poured in upon Vuillaume from all parts of the world.

These instruments, imitations though they were, had high intrinsic

merit; and it is to be remembered that they were copies made from

unrivaled models, with fidelity and care such as only a devoted

worshipper and a great master of his art could attain. He spared no

pains in striving after perfection in the quality of his materials, and

he treated the obscure and difficult problem of the varnish (the secret

of which, as applied by the old Italian masters, seems to have died

with them) with a success which has probably not been equalled by any

other maker since their time. The

number of these instruments bearing his name is enormous,upwards of two

thousand five hundred being known to exist; and many of them he made

throughout with his own hand.... and we have it on the best authority

that every instrument was varnished by his own hand." - —W.E. Hill & Sons, London 1902 It is said that Vuillaume was able to craft such a perfect replica of "Il Cannone", that upon viewing them side by side, Paganini was

unable to tell which was the original. He was only able to recognize

the master instrument upon hearing subtle differences in tone during

playing. The copy violin was eventually passed on to Paganini’s only student, Camillo Sivori. Sivori owned great violins by Nicolò Amati, Stradivari, and Bergonzi, but the Vuillaume was his favourite. When

making these copies, Vuillaume always remained faithful to the

essential qualities of the instruments he imitated - their thickness,

the choice of the woods, and the shape of the arching. The only

differences, always the result of a personal decision, were the colour

of the varnish, the height of the ribs or the length of the

instruments. His most beautiful violins were often named after the

people who owned them (Caraman de Chimay, Cheremetoff, Doria). Vuillaume

occasionally named his instruments: twelve were named after birds, for

example the "Golden Pheasant", "The Thrush" and twelve were named after

the apostles such as "St. Joseph". A few others were also named after

important biblical characters "The Evangelists" and Millant, in his

book on Vuillaume, mentions a "St. Nicholas." A

rare violin by Jean Baptiste Vuillaume (circa 1874, Paris) showcases

inlaid ebony fleur-de-lys designs and is one of the last instruments to

come out of Vuillaume's workshop, made a year before his death. Crafted

for the famous violin dealer David Laurie,

"Label reads: Jean Baptiste Vuillaume a Paris, 3 Rue Demour-Ternes,

expres pour mon ami David Laurie, 1874", numbered 2976 and signed on

the label. It's a copy of a Nicolò Amati violin originally belonging to Prince Youssoupoff (a Russian aristocrat and pupil of Henri Vieuxtemps). Only six copies were made. He also had practice violins, known as "St Cecilia violins", made by his brother Nicolas de Mirecourt. His main contribution to violin making was his work on varnish.

The purfling's joints are often cut on the straight and not on the bias

as was traditional, in the middle in the pin. His brand is burnt at a

length of 1 cm. There is generally a black dot on the joint of the top

under the bridge. He used an external mould. The stop is generally 193

mm long. In this respect he follows to the French 18th century

tradition of a short stop (190 mm), which was traditionally 195 mm long

in Italy and even 200 mm long in Germany. The violin's serial number is

inscribed in the middle inside the instrument. Its date (only the last

two figures) in the upper paraph on the back. His violins of the first

period have large edges and his brand was then burnt inside the middle

bouts. The varnish varied from orange-red to red. After 1860, his

varnish became lighter. In addition to the above-mentioned bow makers, most 19th century Parisian violin makers worked in his workshop, including Hippolyte Silvestre, Jean-Joseph Honoré Derazey, Charles Buthod, Charles-Adolphe Maucotel, Télesphore Barbé and Paul Bailly. Nestor Audinot,

a pupil of Sébastien Vuillaume, himself Jean-Baptiste's nephew,

succeeded him in his workshop in 1875. Vuillaume died at the height of

his career, widely regarded as the pre-eminent luthier of his day.

“ In

1775 Paolo contracted to sell these instruments [the 10 remaining from

his father's workshop] and other things from his father's shop to Count

Cozio di Salabue, one of the most important collectors in history; and

although Paolo died before the transaction was concluded, Salabue

acquired the instruments. Salabue kept the 'Messiah' until 1827, when

he sold it to Luigi Tarisio, a fascinating character who, from small

beginnings, built up an important business dealing in violins. However,

Tarisio could not bear to part with this instrument. Instead, he made

it a favorite topic of conversation, and intrigued dealers on his

visits to Paris with accounts of this marvelous 'Salabue' violin, as it

was then called, taking care, however, never to bring it with him. One

day Tarisio was discoursing to Vuillaume on the merits of this unknown

and marvelous instrument, when the violinist Delphin Alard, who was

present, exclaimed: 'Then your violin is like the Messiah: one always

expects him but he never appears' ('Ah, ça, votre violon est

donc comme le Messie; on l'attend toujours, et il ne parait jamais').

Thus the violin was baptized with the name by which it is still known. ”

“ Vuillaume's

ideal, and by constant study and cultivation of his own rare natural

powers of observation he acquired such an intimate knowledge and

judgement of Stardivari's work in every detail, that he might almost be

said to be better acquainted with the maker's instruments than the

master himself. Vuillaume soon found the sale of violins, issued as new

works without any semblance of antiquity, an unprofitable undertaking

and, recognizing the growing demand in all parts of the world for

instruments resembling the great works of Cremona, he determined to

apply his great skill as a workman, and his extraordinary familiarity

with Stradivari's models, to the construction of faithful copies of the

greatmaster's works. ”