<Back to Index>

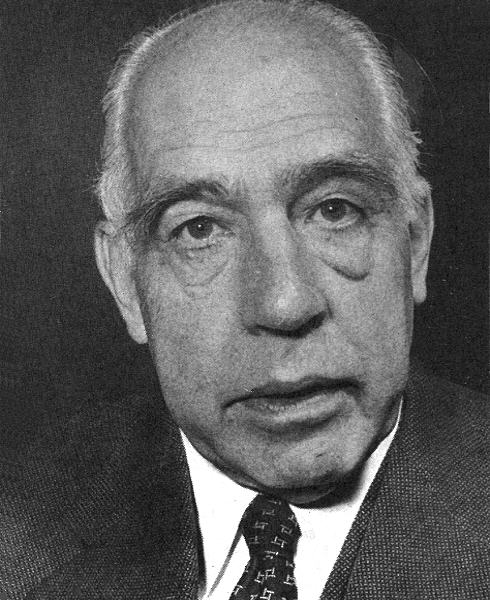

- Physicist Niels Henrik David Bohr, 1885

- Violin Maker Jean Baptiste Vuillaume, 1798

- President of Peru Fernando Belaúnde Terry, 1912

Niels Henrik David Bohr (7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. Bohr mentored and collaborated with many of the top physicists of the century at his institute in Copenhagen. He was part of a team of physicists working on the Manhattan Project. Bohr married Margrethe Nørlund in 1912, and one of their sons, Aage Bohr, grew up to be an important physicist who in 1975 also received the Nobel prize. Bohr has been described as one of the most influential physicists of the 20th century.

Bohr was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1885. His father, Christian Bohr, a devout Lutheran, was professor of physiology at the University of Copenhagen (it is his name which is given to the Bohr shift or Bohr effect), while his mother, Ellen Adler Bohr, came from a wealthy Jewish family prominent in Danish banking and parliamentary circles. His brother was Harald Bohr, a mathematician and Olympic footballer who played on the Danish national team. Niels Bohr was a passionate footballer as well, and the two brothers played a number of matches for the Copenhagen-based Akademisk Boldklub, with Niels in goal. There is, however, no truth in the oft-repeated claim that Niels Bohr emulated his brother Harald by playing for the Danish national team.

In 1903 Bohr enrolled as an undergraduate at Copenhagen University, initially studying philosophy and mathematics. In 1905, prompted by a gold medal competition sponsored by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, he conducted a series of experiments to examine the properties of surface tension, using his father's laboratory in the university, familiar to him from assisting there since childhood. His essay won the prize, and it was this success that decided Bohr to abandon philosophy and adopt physics. As a student under Christian Christiansen he received his doctorate in 1911. As a post-doctoral student, Bohr first conducted experiments under J.J. Thomson at Trinity College, Cambridge. He then went on to study under Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester in England. On the basis of Rutherford's theories, Bohr published his model of atomic structure in 1913, introducing the theory of electrons traveling in orbits around the atom's nucleus, the chemical properties of the element being largely determined by the number of electrons in the outer orbits. Bohr introduced the idea that an electron could drop from a higher-energy orbit to a lower one, emitting a photon (light quantum) of discrete energy. This became a basis for quantum theory.

Niels Bohr and his wife Margrethe Nørlund Bohr had six sons. Their oldest died in a tragic boating accident and another died from childhood meningitis. The others went on to lead successful lives, including Aage Bohr, who became a very successful physicist and, like his father, won a Nobel Prize in physics, in 1975.

In 1916, Niels Bohr became a professor at the University of Copenhagen. With the assistance of the Danish government and the Carlsberg Foundation, he succeeded in founding the Institute of Theoretical Physics in 1921, of which he became its director. In 1922, Bohr was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics "for his services in the investigation of the structure of atoms and

of the radiation emanating from them." Bohr's institute served as a

focal point for theoretical physicists in the 1920s and '30s, and most

of the world's best known theoretical physicists of that period spent

some time there. Bohr also conceived the principle of complementarity:

that items could be separately analyzed as having several contradictory

properties. For example, physicists currently conclude that light

behaves

either as a wave or a stream of particles depending on the experimental

framework — two apparently mutually exclusive properties — on the basis

of this principle. Bohr found philosophical applications for this daringly original principle. Albert Einstein much preferred the determinism of classical physics over the probabilistic new quantum physics (to which Max Planck and

Einstein himself had contributed). He and Bohr had good-natured

arguments over the truth of this principle throughout their lives (Bohr–Einstein debates). Werner Heisenberg worked

as an assistant to Bohr and university lecturer in Copenhagen from 1926

to 1927. It was in Copenhagen, in 1927, that Heisenberg developed his uncertainty principle, while working on the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics. Heisenberg was later to be head of the German atomic bomb project. In 1941, during the German occupation of Denmark in World War II,

Bohr was visited by Heisenberg in Copenhagen. In

1943, shortly before he was to be arrested by the German police, Bohr escaped to Sweden, and then traveled to London. Niels Bohr worked at the top-secret Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico, U.S., on the Manhattan Project, where he was known by the assumed name of Nicholas Baker for security reasons. His

role in the project was important and was a knowledgeable consultant or

"father confessor" on the project. He was concerned about a nuclear

arms race, and is quoted as saying, "That is why I went to America. They didn't need my help in making the atom bomb." Bohr believed that atomic secrets should be shared by the international scientific community. After meeting with Bohr, J. Robert Oppenheimer suggested Bohr visit President Franklin D. Roosevelt to convince him that the Manhattan Project should

be shared with the Russians in the hope of speeding up its results.

Roosevelt suggested Bohr return to the United Kingdom to try to win

British approval. Winston Churchill disagreed

with the idea of openness towards the Russians to the point that he

wrote in a letter: "It seems to me Bohr ought to be confined or at any

rate made to see that he is very near the edge of mortal crimes." After the war Bohr returned to Copenhagen, advocating the peaceful use of nuclear energy. When awarded the Order of the Elephant by the Danish government, he designed his own coat of arms which featured a taijitu (symbol of yin and yang) and the Latin motto contraria sunt complementa: opposites are complementary. He died in Copenhagen in 1962 of heart failure. He is buried in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen.