<Back to Index>

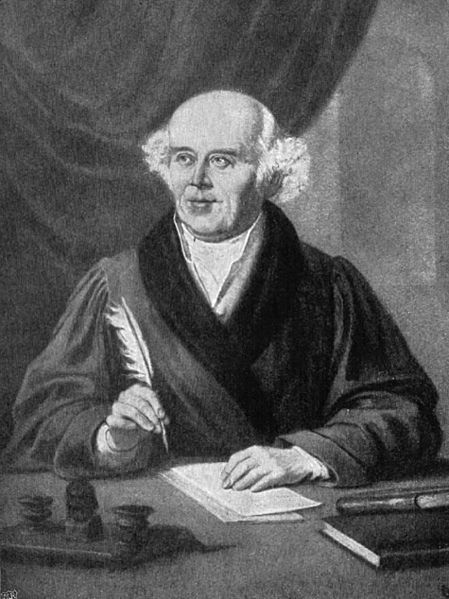

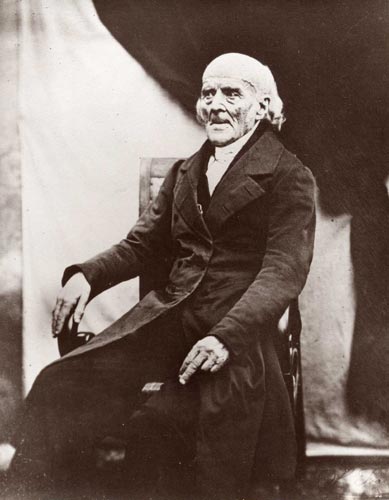

- Physician Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann, 1755

- Composer Eugen Francis Charles d'Albert, 1864

- U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, 1794

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann (10 April 1755 – 2 July 1843), a German physician, created an alternative medicine practice called homeopathy.

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann was born in Meissen, Saxony. His father, along with many other family members, was a painter and designer of porcelain, for which the town of Meissen is famous. As a young man, Hahnemann became proficient in a number of languages, including English, French, Italian, Greek and Latin. He eventually made a living as a translator and teacher of languages, gaining further proficiency in "Arabic, Syriac, Chaldaic and Hebrew".

Hahnemann studied medicine for two years at Leipzig. Citing Leipzig's lack of clinical facilities, he moved to Vienna, where he studied for ten months. After one term of further study, he graduated MD at the University of Erlangen on 10 August 1779, qualifying with honors. His poverty may have forced him to choose Erlangen, as the school's fees were lower. Hahnemann's thesis was titled Conspectus adfectuum spasmodicorum aetiologicus et therapeuticus. [A Dissertation on the Causes and Treatment of Cramps]

In

1781,

Hahnemann

took a village doctor’s position in the copper mining

area of Mansfeld, Saxony. He soon married Johanna

Henriette Kuchler and would eventually have eleven children. After abandoning medical

practice, and while working as a translator of scientific and medical

textbooks, Hahnemann travelled around Saxony for many years, staying in

many different towns and villages for varying lengths of time, never

living far from the River

Elbe and

settling

at different times in Dresden, Torgau, Leipzig and Köthen

(Anhalt) before finally moving to

Paris in June 1835. Hahnemann

claimed

that the medicine of his time did as much harm as good: My

sense of duty would not easily allow me to treat the unknown

pathological state of my suffering brethren with these unknown

medicines. The thought of becoming in this way a murderer or malefactor

towards the life of my fellow human beings was most terrible to me, so

terrible and disturbing that I wholly gave up my practice in the first

years of my married life and occupied myself solely with chemistry and writing. After

giving up his practice around 1784, Hahnemann made his living chiefly

as a writer and translator, while resolving also to investigate the

causes of medicine's alleged errors. While translating William

Cullen's A

Treatise on the Materia Medica,

Hahnemann encountered the claim that cinchona,

the

bark of a Peruvian tree, was effective in treating malaria because of its astringency. Hahnemann

believed that other astringent substances are not effective

against malaria and began to research cinchona's effect on the human

body by self-application. Noting that the drug induced malaria-like

symptoms in himself, he concluded that it would do so in any healthy

individual. This led him to postulate a healing principle: "that which

can produce a set of symptoms in a healthy individual, can treat a sick

individual who is manifesting a similar set of symptoms." This principle, like cures like,

became the basis for an approach to medicine which he gave the name homeopathy.

He

first used the term homeopathy in his essay Indications of the

Homeopathic Employment of Medicines in Ordinary Practice, published in Hufeland's

Journal in 1807. Hahnemann

tested

substances for the effect they produced on a healthy individual

and tried to deduce from this the ills they would heal. From his

research, he initially concluded that ingesting substances to produce

noticeable changes in the body resulted in toxic effects. He then

attempted to mitigate this problem through exploring dilutions of the

compounds he was testing. He claimed that these dilutions, when

prepared according to his technique of succussion (systematic mixing through

vigorous shaking) and potentization,

were

still

effective in alleviating the same symptoms in the sick. Hahnemann

began practicing this new technique, which attracted other doctors

c.1792. He

first

published an article about the homeopathic approach in a German

language medical

journal in 1796. Following a series of further essays, he published in

1810, his The

Organon

of

the Healing Art, the first

systematic treatise and

containing all his detailed instructions on the subject. The Organon is

widely regarded as a remodelled form of an essay he published in 1806

called "The Medicine of Experience," which had been published in

Hufeland's Journal. Of the Organon, Dudgeon states it "was an

amplification and extension of his "Medicine of Experience," worked up

with greater care, and put into a more methodical and aphoristic form,

after the model of the Hippocratic writings."

Around

the

start

of the 19th century Hahnemann developed a theory, propounded

in his 1803 essay On

the Effects of Coffee from Original Observations, that many

diseases are caused by coffee. Hahnemann later abandoned

the coffee theory in favour of the theory that disease is caused by

Psora, but it has been noted that the list of conditions Hahnemann

attributed to coffee was similar to his list of conditions caused by

Psora. The coffee theory has been described as "a good example both of

Hahnemann's superior mental powers and of his occasional tendency to

make up a grand theory from scant evidence". In

early

1811 Hahnemann moved his family

back to Leipzig with the intention of

teaching his new medical system at the University of

Leipzig. In accordance with the university statutes, he became a

faculty member by submitting and defending a thesis on a medical topic

of his choice. On 26 June 1812, Hahnemann presented a Latin thesis, entitled "A Medical Historical

Dissertation on the Helleborism of the Ancients." Hellebore,

a

number

of species of poisonous flowering plants, related to Buttercup and Magnolia. Hahnemann

continued practicing and researching homeopathy, as well as writing and

lecturing for the rest of his life. He died in 1843 in Paris, at 88

years of age, and is entombed in a mausoleum at Paris's Père

Lachaise cemetery. While

there are a few living descendants of Hahnemann’s older sister

Charlotte (1752 – 1812),

there

is only one known living descendant of Hahnemann himself, Mr

Charles Tankard-Hahnemann (7th generation descendant of Dr Samuel

Hahnemann). His

father, Mr William Herbert Tankard-Hahnemann (1922 – 2009), the great,

great, great grandson of Samuel Hahnemann died on 12 January 2009 (his

87th birthday) after 22 years of active patronage of the British

Institute of Homœpathy.

As

a young boy, William remembered his mother telling him of her visits

to her ‘grand-dad Leo’ at Ventnor, Isle of Wight. Later William

Hahnemann knew that this was Dr Leopold Süβ-Hahnemann, Dr Samuel

Hahnemann’s grandson, the only son of his favourite daughter Amelie

(1789 – 1881). Dr Süβ-Hahnemann was the only member of the

Hahnemann

family to be present at Samuel Hahnemann’s funeral, apart from

Hahnemann’s second wife Mélanie, in Paris in 1843 and at his

subsequent re-burial in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in east

Paris, where only persons of truly notable distinction are interred.

Subsequently Leopold emigrated from France to England where he

practised homœopathy in London. He retired to the Isle of Wight and

died there at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Dr Leopold

Süβ-Hahnemann’s youngest daughter, Amalia had two children,

Winifred (born 1898) and Herbert. Mr William Tankard-Hahnemann was

Winifred’s son. Apart from serving as the patron of the British

Institute of Homœopathy, he also had a distinguished career in the City

of London and was honoured by being appointed as a ‘Freeman of the City

of London’.