<Back to Index>

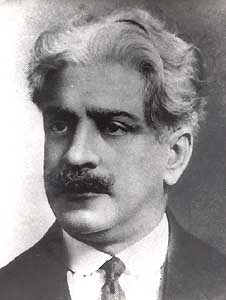

- Physician Oswaldo Gonçalves Cruz, 1872

- Composer Charles Louis Ambroise Thomas, 1811

- 1st President of Slovakia Michal Kováč, 1930

PAGE SPONSOR

Oswaldo Gonçalves Cruz, better known as Oswaldo Cruz (August 5, 1872, São Luíz do Paraitinga, São Paulo state, Brazil – February 11, 1917, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro state) was a Brazilian physician, bacteriologist, epidemiologist and public health officer and the founder of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute. He also occupied the 5th chair of the Brazilian Academy of Letters from 1912 until his death in 1917.

Oswaldo

Gonçalves Cruz was born on August 5, 1872 in São Luis do

Paraitinga, a small city in São Paulo State, to the physician

Bento Gonçalvez Cruz and Amália Bulhões Cruz.

Still a child, he moved to Rio de Janeiro with his family. At the age

of 15 he started to study at the Faculty of Medicine of Rio de Janeiro and in 1892 he graduated as medical doctor with a thesis on water as vehicle for the propagation of microbes. Inspired by the great work of Louis Pasteur, who had developed the germ theory of disease, four years later he went to Paris to specialize in Bacteriology at the Pasteur Institute,

which gathered the great names of this branch of science of that time.

He was financed by his father-in-law, a wealthy Portuguese merchant. Cruz found the seaport of Santos ravaged by a violent epidemic of bubonic plague that threatened to reach Rio de Janeiro and engaged himself immediately in the combat of this disease. The mayor of Rio de Janeiro authorized

the construction of a plant for manufacturing the serum against the

disease which had been developed at the Pasteur Institute by Alexandre Yersin and

coworkers, and asked the institution for a scientist who could bring to

Brazil this know-how. The Pasteur Institute responded that such a

person was already available in Brazil and he was Dr. Oswaldo Cruz. Thus, on May 25, 1900, the Federal Serotherapy Institute destined to the production of sera and vaccines against

the bubonic plague was created with the Baron Pedro Afonso as Director

General and the young bacteriologist Oswaldo Cruz as Technical

Director. The new Institute was established in the old farm of

Manguinhos at the western shores of Guanabara Bay.

In 1902, Cruz accepted the office of Director General of the new

institute and soon amplified its scope of activities, now no longer

restricted to the production of sera but also dedicated to basic and

applied research and to the building of human resources. In the

following year, Oswaldo Cruz was appointed Director General of Public

Health, a position corresponding to that of a today's Minister of

Health. Using the Federal Serotherapy Institute as technical-scientific

base, he started a quick succession of memorable sanitation campaigns. His first adversary: a series of yellow fever endemics, which had earned Rio de Janeiro the sinister reputation of Foreigners' Grave. Between 1897 and 1906, 4,000 European immigrants had died there from this disease. Cruz

was initially successful in the sanitary campaign against the bubonic

plague, to which end he used obligatory notification of cases,

isolation of sick people, treatment with the sera produced at

Manguinhos and extermination of the rats populating the city. In 1904, a smallpox epidemic

was threatening the capital. In the course of the first five months of

that year, more than 1,800 persons had already been hospitalized. A law

imposing smallpox vaccination of children had existed since 1837 but

had never been put into practice. Therefore, on June 9, 1904, following

a proposal by Oswaldo Cruz, the government presented a bill to the

Congress requesting the reestablishment of obligatory smallpox

vaccination. The extremely rigid and severe provisions of this

instrument terrified the people. Popular opposition against Oswaldo

Cruz increased sharply and opposition newspapers started a violent

campaign against this measure and the federal government in general.

Members of the parliament and labor unions protested. An

Anti-vaccination League was organized. On November 10, the Vaccine Revolt exploded in Rio. Violent confrontations with the police ensued, with strikes, barricades,

and shootings in the streets, as the population rose in protest against

the government. On November 14, the Military Academy adhered to the

revolt but the cadets where dispersed after an intense shooting. The

government declared a state of siege.

On November 16, the uprising was controlled and the obligatory

vaccination was suspended. But in 1908, a violent smallpox epidemic

made the people rush en masse to the vaccination units and Cruz was

vindicated, and his merit recognized. Among

the international scientific community, his prestige was already

uncontested. In 1907, on occasion of the 14th International Congress on

Hygiene and Demography in Berlin, he was awarded with the gold medal in

recognition of the sanitation of Rio de Janeiro. In 1909, Oswaldo Cruz

retired from the position as Director General for Public Health,

dedicating himself exclusively to the Manguinhos Institute, which has

been named after him. From the Institute he organized important

scientific expeditions, which allowed a better knowledge about the

health and life conditions in the interior of the country and

contributed to the colonization of different regions. He eradicated the

urban yellow fever in the State of Pará. His sanitation campaign in the state of Amazonas allowed concluding the construction of the Madeira-Mamoré railroad, which was interrupted due to the great number of deaths of malaria and yellow fever among the workers. In

1913, he was elected a member of the Brazilian Academy of Arts and

Letters. In 1915, due to health problems, he resigned from the

directorship of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute and moved to

Petrópolis, a small city in the mountains near Rio. On August

18, 1916, he was elected mayor of that city and outlined an extensive urbanization project he would not see implemented. In the morning of February 11, 1917, at only 44 years of age, he died of kidney failure. As

a consequence of the short but fruitful life of Dr. Oswaldo Cruz, an

extremely important scientific and health institution was born, which

marked the beginning of experimental medicine in Brazil in many areas.

To this day it exerts a strong influence on Brazilian science,

technology and public health.