<Back to Index>

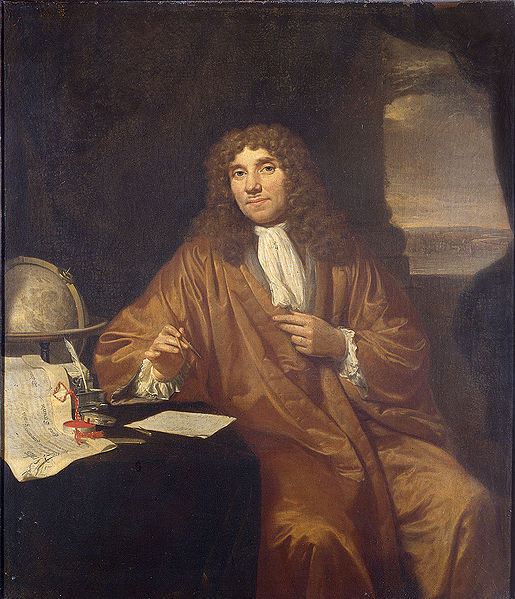

- Microbiologist Anthonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek, 1632

- Novelist Dorothea von Schlegel, 1764

- Emperor of the Roman Empire Titus Flavius Domitianus, 51

PAGE SPONSOR

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek (in Dutch also Anthonie, Antoni, or Theunis, in English, Antony or Anton; October 24, 1632 – August 26, 1723) was a Dutch tradesman and scientist from Delft, Netherlands. He is commonly known as "the Father of Microbiology", and considered to be the first microbiologist. He is best known for his work on the improvement of the microscope and for his contributions towards the establishment of microbiology. Using his handcrafted microscopes he was the first to observe and describe single celled organisms, which he originally referred to as animalcules, and which we now refer to as microorganisms. He was also the first to record microscopic observations of muscle fibers, bacteria, spermatozoa and blood flow incapillaries (small blood vessels). Van Leeuwenhoek did not author any books, although he did write many letters.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was born in Delft, The Netherlands, on October 24, 1632. He was the son of the basket maker Philips Teunisz Leeuwenhoeck and Margriete Jacobsdr van den Berch, who were married in Delft on 30 Jan 1622. The Leeuwenhoeks lived in a comfortable brick house on Leeuwenpoort Street. Before his sixth birthday two of his younger sisters and his father had died, and his mother was left with five young children. On 18 Dec 1640 she married Jacob Molijn and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was sent to boarding school in the village of Warmond, near Leiden. Soon after he was invited by an uncle to live with him in Benthuizen, a village northeast of Delft. At age 16, his stepfather died and his mother decided it was time for Antonie to learn a trade. He secured an apprenticeship with a Scottish cloth merchant in Amsterdam as a bookkeeper and cashier. In 1653, Van Leeuwenhoek saw his first simple microscope, a magnifying glass mounted on a small stand used by textile merchants, capable of magnifying to a power of 3. He soon acquired one for his own use. In 1654, he left Amsterdam, moved back to Delft for the rest of his life and started his own lucrative drapery business there. On July 11, he married Berber (Barbara) de Mey, the daughter of a cloth merchant and settled as a linen-draper. He was registered as Anthoni Leeuwenhouck. Four out of his five children died young. In 1660, he was appointed chamberlain of the Lord Regents of Delft. In 1666 his wife died and in 1671 he married Cornelia Swalmius, the daughter of a minister. Van Leeuwenhoek outlived his second wife, who died in 1694.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek did not learn Latin, or attend university, but in 1669 he obtained a degree in surveying; it is possible he was involved in Subdivision Plans for the city of Delft. Demonstrable is his appointment in 1676 as a bailiff. In 1679 he got a post as a gauger, an inspector of wine and beer at the local publicans, who were heavily taxed for the amount that was sold.

Van Leeuwenhoek's interest in microscopes and a familiarity with glass processing led to one of the most significant, and simultaneously well-hidden, technical insights in the history of science. By placing the middle of a small rod of soda lime glass in a hot flame, Van Leeuwenhoek could pull the hot section apart like taffy to create two long whiskers of glass. By then reinserting the end of one whisker into the flame, he could create a very small, high-quality glass sphere. These spheres became the lenses of his microscopes, with the smallest spheres providing the highest magnifications. An experienced businessman, Leeuwenhoek realized that if his simple method for creating the critically important lens was revealed, the scientific community of his time would likely disregard or even forget his role in microscopy. He therefore allowed others to believe that he was laboriously spending most of his nights and free time grinding increasingly tiny lenses to use in microscopes, even though this belief conflicted both with his construction of hundreds of microscopes and his habit of building a new microscope whenever he chanced upon an interesting specimen that he wanted to preserve.

Van Leeuwenhoek used samples and measurements to estimate numbers of microorganisms in units of water. Van

Leeuwenhoek made good use of the huge lead provided by his method. He

studied a broad range of microscopic phenomena, and shared the

resulting observations freely with groups such as the English Royal Society. Such work firmly established his place in history as one of the first and most important explorers of the microscopic world. After

developing his method for creating powerful lenses and applying them to

study of the microscopic world, Van Leeuwenhoek was introduced via

correspondence to the Royal Society of London by the famous Dutch Physician Reinier de Graaf.

He soon began to send copies of his recorded microscopic observations

to the Royal Society. In 1673 his earliest observations were published by the Royal Society in its journal: Philosophical Transactions. Amongst those published were Van Leeuwenhoek's accounts of bee mouthparts and stings. Despite

the initial success of Van Leeuwenhoek's relationship with the Royal

Society, this relationship was soon severely strained. In 1676 his

credibility was questioned when he sent the Royal Society a copy of his

first observations of microscopic single-celled organisms. Previously,

the existence of single-celled organisms was entirely unknown. Thus,

even with his established reputation with the Royal Society as a

reliable observer, his observations of microscopic life were initially

met with skepticism. Eventually, in the face of Van Leeuwenhoek's

insistence, the Royal Society arranged to send an English vicar, as

well as a team of respected jurists and doctors, to Delft, to determine

whether it was in fact Van Leeuwenhoek's ability to observe and reason

clearly, or perhaps the Royal Society's theories of life itself that

might require reform. Finally in 1680, Van Leeuwenhoek's observations

were fully vindicated by the Society. Van

Leeuwenhoek's vindication resulted in his appointment as a Fellow of

the Royal Society in that year. After his appointment to the Society,

he wrote approximately 560 letters to the Society and other scientific

institutions over a period of 50 years. These letters dealt with the

subjects he had investigated. Even when dying, Van Leeuwenhoek kept

sending letters full of observations to London. The last few also

contained a precise description of his own illness. He suffered from a

rare disease, an uncontrolled movement of the midriff, which is now named Van Leeuwenhoek's disease. He died at the age of 90, on August 26, 1723 and was buried four days later in the Oude Kerk (Delft). In 1981 the British microscopist Brian J. Ford found that Van Leeuwenhoek's original specimens had survived in the collections of the Royal Society of London. They

were found to be of high quality, and were all well preserved. Ford

carried out observations with a range of microscopes, adding to our

knowledge of Van Leeuwenhoek's work. Van

Leeuwenhoek ground more than 500 optical lenses. He also created at

least 250 microscopes, of differing types, of which only nine survive.

His microscopes were made of silver or copper frames, holding

hand-ground lenses. Those that have survived are capable of

magnification up to 275 times. It is suspected that Van Leeuwenhoek

possessed some microscopes which could magnify up to 500 times.

Although he has been widely regarded as a dilettante or amateur, his

scientific research was of remarkably high quality. Van Leeuwenhoek's main discoveries are: the infusoria (protists in modern zoological classification), in 1674; the bacteria, (e.g. large Selenomonads from the human mouth), in 1676; the spermatozoa in 1677. Van Leeuwenhoek had troubles with Dutch theologists about his practice; the banded pattern of muscular fibers, in 1682. In 1687 he reported his research on the coffee bean.

He roasted the bean, cut it into slices and saw a spongeous interior.

The bean was pressed, and an oil appeared. He boiled the coffee with

rain water twice, set it aside (and probably drank it slowly). He was visited by Leibniz, William III of Orange and his wife, the Amsterdam burgomaster (the mayor) Johan Huydecoper, the latter very interested in collecting and growing plants for the Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam and all gazed at the tiny creatures. Nicolaes Witsen sent him a map of Tartaria and a mineral found near the origin of the river Amur. In 1698 Van Leeuwenhoek was invited in the boat of tsar Peter the Great.

On the occasion Van Leeuwenhoek presented the tsar an "eel-viewer", so

Peter could study the blood circulation, whenever he wanted.

Van Leeuwenhoek maintained throughout his life that there were aspects of microscope construction "which I only keep for myself",

in particular his most critical secret of how he created lenses. For

many years no-one was able to reconstruct Van Leeuwenhoek's design

techniques. However, in 1957 C.L. Stong used thin glass thread fusing

instead of polishing, and successfully created some working samples of

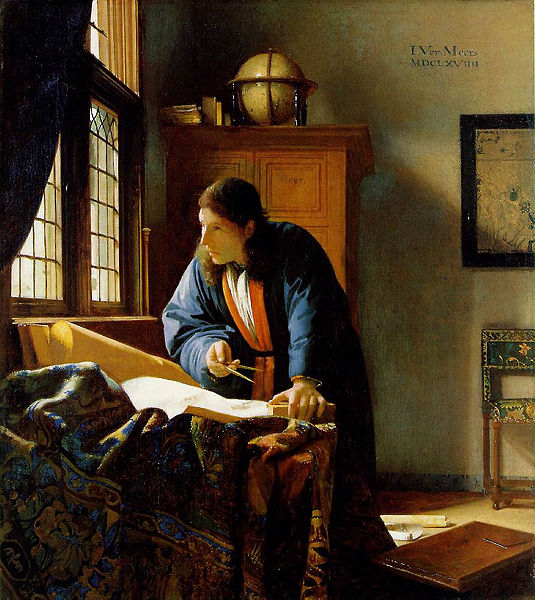

a Leeuwenhoek design microscope. Such a method was also discovered independently by A. Mosolov and A. Belkin in the Novosibirsk State Medical Institute. Van Leeuwenhoek was a contemporary of another famous Delft citizen, painter Johannes Vermeer,

who was baptized just four days earlier. It has been suggested that he

is the man portrayed in two of Vermeer's paintings of the late 1660s, The Astronomer and The Geographer.

However, others argue that there appears to be little physical

similarity. Because they were both relatively important men in a city

with only 24,000 inhabitants, it is likely that they were at least

acquaintances. Also, it is known that Van Leeuwenhoek acted as the executor of the will when the painter died in 1675. In A Short History of Nearly Everything Bill Bryson alludes to rumors that Vermeer's mastery of light and perspective came from use of a camera obscura produced by Van Leeuwenhoek. This is one of the examples of the controversial Hockney–Falco thesis, which claims that some of the Old Masters used optical aids to produce their masterpieces.

Van Leeuwenhoek was a Dutch Reformed Calvinist. He

often referred with reverence to the wonders God designed in making

creatures great and small. He believed that his amazing discoveries

were merely further proof of the great wonder of God's creation. Van Leeuwenhoek's discovery that smaller organisms procreate similarly to

larger organisms challenged the contemporary belief, generally held by

the 17th century scientific community, and tacitly endorsed by the

Church of the time, that such organisms generated spontaneously. The position of the Church on the exact nature of the spontaneous generation of smaller organisms was ambivalent.