<Back to Index>

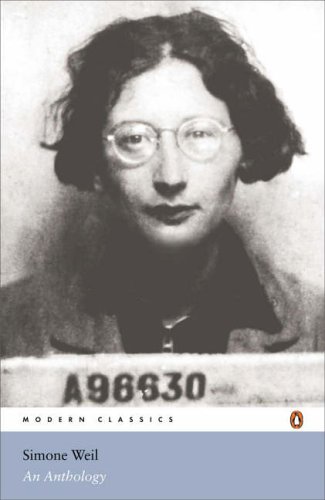

- Philosopher Simone Weil, 1909

- Writer Gertrude Stein, 1874

- President of Perú and President of Bolivia Antonio José de Sucre y Alcalá, 1795

PAGE SPONSOR

Simone Weil (3 February 1909 in Paris, France – 24 August 1943 in Ashford, Kent, England), was a French philosopher, Christian mystic, and social activist.

Weil was born in Paris to Alsatian agnostic Jewish parents who fled the annexation of Alsace - Lorraine to Germany. She grew up in comfortable circumstances, as her father was a doctor. Her only sibling was André Weil, who would go on to become one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century. She suffered throughout her life from severe headaches, sinusitis, and poor physical coordination, and spared no scrutiny to these in her philosophical writings. Her brilliance, ascetic lifestyle, introversion, and eccentricity limited her ability to mix with others, but not to teach and participate in political movements of her time. She wrote extensively with both insight and breadth about political movements of which she was a part and later about spiritual mysticism. Weil biographer Gabriella Fiori writes that Weil was "a moral genius in the orbit of ethics, a genius of immense revolutionary range."

Weil was a precocious student, proficient in ancient Greek by the age of 12. She later learned Sanskrit after reading the Bhagavad Gita. Like the Renaissance thinker, Pico della Mirandola, her interests in other religions were universalist, and she attempted to understand each religious tradition as expressive of transcendent wisdom. In her teens she studied at the Lycée Henri IV under the tutelage of her admired teacher Émile Chartier, more commonly known as "Alain". In 1928, Weil finished first in the entrance examination for the École Normale Supérieure; Simone de Beauvoir, her more long lived and famous peer, finished second. During these years Weil attracted much attention with her radical opinions. She was called the "Red virgin", and even "The Martian" by her admired mentor.

At the École Normale Supérieure she studied philosophy, receiving her Agrégation diploma in 1931. Weil taught philosophy at a secondary school for girls in Le Puy and teaching was her primary employment during her short life. Most of the writing for which she is known was published posthumously.

Weil often took actions out of sympathy with the working class. In 1915, when she was only six years old, she refused sugar in solidarity with the troops entrenched along the Western Front. In 1919, at 10 years of age, she declared herself a Bolshevik. In her late teens, she became involved in the workers' movement. She wrote political tracts, marched in demonstrations, and advocated workers' rights. At this time, she was a Marxist, pacifist, and trade unionist. While teaching in Le Puy, she became involved in local political activity, supporting the unemployed and striking workers despite criticism by some. She also wrote about social and economic issues, including Oppression and Liberty and numerous short articles for trade union journals. This work criticised popular Marxist thought, and gave a pessimistic account of the limits of both capitalism and socialism.

She participated in the French general strike of 1933, called to protest unemployment and wage cuts. The following year she took a 12-month leave of absence from her teaching position to work incognito as a laborer in two factories, one owned by Renault, believing that this experience would allow her to connect with the working class. Her poor health and inadequate physical strength forced her to quit after some months. In 1935 she resumed teaching, and donated most of her income to political causes and charitable endeavors.

In 1936, despite her professed pacifism, she fought in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side. She identified herself as an anarchist and joined the Sébastien Faure Century, the French speaking section of the anarchist militia.

However, her clumsiness repeatedly put her comrades at risk. After

burning herself over a cooking fire, she left Spain to recuperate in Assisi. She continued to write essays on labor and management, and war and peace.

While in Assisi in the spring of 1937, she experienced a religious ecstasy in the same church in which Saint Francis of Assisi had prayed, which led her to pray for the first time in her life as Cunninham relates:

"Below the town is the beautiful church and convent of San Damiano where Saint Clare once lived. Near that spot is the place purported to be where Saint Francis composed the larger part of his "Canticle of Brother Sun." Below the town in the valley is the ugliest church in the entire environs: the massive baroque basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels, finished in the seventeenth century and rebuilt in the nineteenth century, which houses a rare treasure: a tiny romanesque chapel that stood in the days of Saint Francis -- the "Little Portion" where he would gather his brethren. It was in that tiny chapel that the great mystic Simone Weil first felt compelled to kneel down and pray."

She had another, more powerful, revelation a year later and, from 1938 on, her writings became more mystical and spiritual, while retaining their focus on social and political issues. She was attracted to Roman Catholicism, but declined to be baptized; she explained this refusal in letters published in Waiting for God. During World War II, she lived for a time in Marseille, receiving spiritual direction from a Dominican friar. Around this time she met the French Catholic author Gustave Thibon, who later edited some of her work.

Weil did not limit her curiosity to Christianity. She was keenly interested in other religious traditions — especially the Greek and Egyptian mysteries, Hinduism (especially the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita), and Mahayana Buddhism. She believed that all these and others were valid paths to God. She was, nevertheless, opposed to religious syncretism, claiming that it effaced the particularity of the individual traditions:

Each religion is alone true, that is to say, that at the moment we are thinking of it we must bring as much attention to bear on it as if there were nothing else...A "synthesis" of religion implies a lower quality of attention.

In 1942, she traveled to the USA with her family. Weil spent this time living briefly in New York City, in Harlem, amongst the poor. She is remembered to have attended daily Mass at Corpus Christi Church there, where the Columbia student and future Trappist monk Thomas Merton was later to be received into the Roman Catholic Church. Long believed not to have sought baptism, there is now evidence, including a claim from a priest who knew her, that she was baptized shortly before her death. After New York, she went to London, where she joined the French Resistance. The punishing work regime she assumed soon took a heavy toll; in 1943 she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and instructed to rest and eat well. However, she refused special treatment because of her long standing political idealism and activism and her detachment from material things. Instead, she limited her food intake to what she believed residents of the parts of France occupied by the Germans ate. She most likely ate even less, as she refused food on most occasions. Her condition quickly deteriorated, and she was moved to a sanatorium in Ashford, Kent, England.

After a lifetime of battling illness and frailty, Weil died in August 1943 from cardiac failure at the age of 34. The coroner's report said that "the deceased did kill and slay herself by refusing to eat whilst the balance of her mind was disturbed."

To

this day, the cause of her death remains a subject of debate for many.

Some claim that her refusal to eat came from her desire to express some

form of solidarity toward the victims of the war. Others think that

Weil's self–starvation occurred after her study of Schopenhauer (in

his chapters on Christian saintly asceticism and salvation, he had

described self–starvation as a preferred method of self–denial).

However, Simone Pétrement,

one of Weil's first and most significant biographers, considers that

the coroner's report was simply mistaken. Basing herself on letters

written by the personnel of the sanatorium at which Simone Weil was

treated, Pétrement affirms that Weil asked for food on different

occasions while she was hospitalized and even ate a little bit a few

days before her death; according to her, it is in fact Weil's poor

health condition that eventually made her unable to eat.