<Back to Index>

- Neurologist António Caetano de Abreu Freire Egas Moniz, 1874

- Writer Wilhelm Hauff, 1802

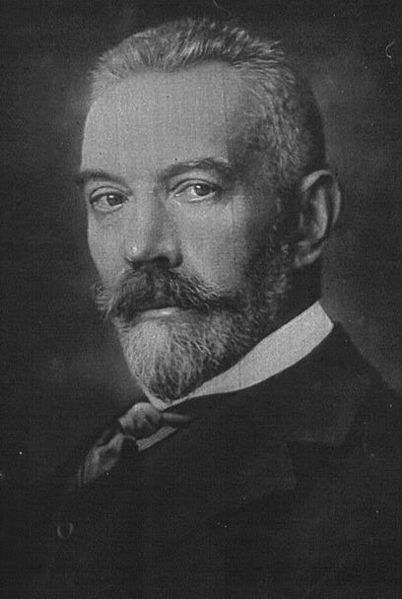

- 5th Chancellor of the German Empire Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, 1856

PAGE SPONSOR

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (November 29, 1856 – January 1, 1921) was a German politician and statesman who served as Chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917.

Bethmann Hollweg was born in Hohenfinow, Brandenburg, the son of Prussian official Felix von Bethmann Hollweg. His grandfather was August von Bethmann Hollweg, who had been a prominent law scholar, president of Frederick William University in Berlin, and Prussian Minister of Culture. His great grandfather was Johann Jakob Hollweg, who had married a daughter of the Frankfurt am Main banking family of Bethmann, which attained great prosperity in the 18th century.

Cosima Wagner was his relative from the von Bethmanns side, and his mother Isabella de Rougemont was French Swiss. A June 1919 Associated Press report from Berlin refers to Bethmann Hollweg as of Jewish descent. An article in Current Literature (July - December 1909) explains the new chancellor's origins this way: that he "had the social disadvantage of Jewish descent, the original Bethmann having been expelled from Holland in the seventeenth century for being a Hebrew. A hundred years later one Hollweg wedded a damsel of the house of Bethmann and the two names were hyphenated into one." British journalist Jonathan Carr argues that this is incorrect; he writes that the mistake is made in part because the name looks Jewish, and also because the rise of the Bethmanns in banking coincided with that of the Rothschilds in the same city.

He was educated at the boarding school of Schulpforta and at the Universities of Strasbourg, Leipzig and Berlin. Entering the Prussian administrative service in 1882 he rose to the position of the President of the Province of Brandenburg in 1899. In 1889, Bethmann Hollweg married Martha von Pfuel, niece of Ernst von Pfuel, Prime Minister of Prussia. From 1905 to 1907 Bethmann Hollweg served as Prussian Minister of Interior, then as Imperial State Secretary for the Interior from 1907 to 1909. In 1909, on the resignation of Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, Bethmann Hollweg was appointed to succeed him.

In foreign policy, he pursued a policy of détente with Britain, hoping to come to some agreement that would put a halt to the two countries' ruinous naval arms race, but failed, largely due to the opposition of German Naval Minister Alfred von Tirpitz. Despite the increase in tensions due to the Second Moroccan Crisis of 1911, Bethmann Hollweg did improve relations with Britain to some extent, working with British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey to alleviate tensions during the Balkan Crises of 1912 - 1913, and negotiating treaties over an eventual partition of the Portuguese colonies and the Berlin - Baghdad railway. In domestic politics, Bethmann Hollweg's record was also mixed, and his policy of the "diagonal", which endeavoured to maneuver between the Socialists and Liberals of the left and the right wing nationalists of the right, only succeeded in alienating most of the German political establishment.Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, Bethmann Hollweg and Foreign Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow were instrumental in urging the Austrians to take a tough stand against Serbia, and later, took steps to prevent Grey's efforts to impose a peaceful solution on the quarreling parties. In the last days before the outbreak of war, however, he seems to have had some second thoughts, and he took half hearted measures to support Grey's proposals of mediation, until Russia's mobilization on July 31, 1914, took the matter out of his hands.

Bethmann Hollweg, much of whose foreign policy before the war had been guided by his desire to establish good relations with Britain, was particularly upset by Britain's declaration of war following German violation of Belgium's neutrality in the course of her invasion of France, reportedly asking the departing British Ambassador Goschen how Britain could go to war over a "mere scrap of paper" (the Treaty of London of 1839 which guaranteed Belgium's neutrality), a remark which would become infamous for its demonstration of German insensitivity to international law and treaty rights. However, it is accepted that Hollweg was involved closely in the decisions that authorised plans to destabilise Britain's colonies, most notably the Hindu German Conspiracy.

During

the war, Bethmann Hollweg has usually been seen as having generally

attempted to pursue a relatively moderate policy, but having been

frequently outflanked by the military leaders, who played an

increasingly important role in the direction of all German policy.

However, this view has been partially superseded, as the work of

historian Fritz Fischer in

the 1960s showed that Bethmann Hollweg made more concessions to the

nationalist right than had previously been thought. He supported the

goal of ethnically cleansing Poles from the Polish Border Strip, as well germanisation of Polish territories by settlement of German colonists. He presented the September programm, which outlined the aggressively expansionist goals for the war. After Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff replaced the more ineffectual Erich von Falkenhayn at the General Staff in the summer of 1916, his hopes for American President Woodrow Wilson's

mediation at the end of 1916 came to nothing, and, over Bethmann

Hollweg's objections, Hindenburg and Ludendorff forced the adoption of

unrestricted submarine warfare in March 1917, which led to the United

States's entry into the war the next month. Bethmann Hollweg, all

credibility and power lost, remained in office until July of that year,

when a Reichstag revolt, resulting in the passage of the famous Peace

Resolution by an alliance of the Social Democratic, Progressive, and

Center parties, forced his resignation and replacement by the political

non-entity Georg Michaelis. Turkey,

allied with Germany during the war, pursued a campaign of mass

expulsion and killings against Armenians beginning in 1915. Despite

numerous dispatches from German diplomats urging action to be taken,

the Reichskanzler refused to step in on behalf of the Armenians.

Special Ambassador Wolff - Metternich addressed Bethmann Hollweg on 7 December 1915 from Constantinople: On 16 December, Bethmann Hollweg wrote in the margin:

Bethmann

Hollweg spent the short remainder of his life in retirement, writing

his memoirs. A little after Christmas 1920, he caught a cold which

developed into acute pneumonia. He died from this illness on January 1,

1921. His wife died in 1914 and he lost his eldest son in the war. He

was survived by a daughter, Countess Zeech, wife of the Secretary of

the Russian Legation at Munich.