<Back to Index>

- Cartographer Abraham Ortelius, 1527

- Architect Peter Behrens, 1868

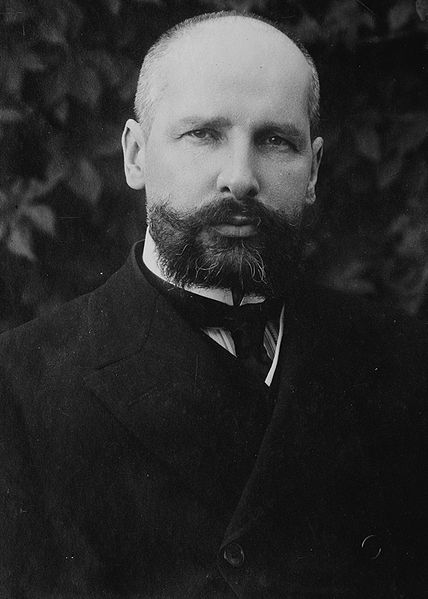

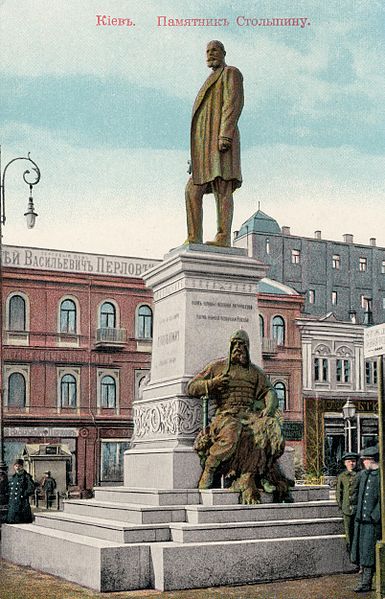

- 3rd Prime Minister of Imperial Russia Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin, 1862

PAGE SPONSOR

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin (Russian: Пётр Аркадьевич Столыпин) (14 April [O.S. 2 April] 1862– September 18 [O.S. September 5] 1911) served as Nicholas II's Chairman of the Council of Ministers — the Prime Minister of Russia — from 1906 to 1911. His tenure was marked by efforts to repress revolutionary groups, as well as for the institution of noteworthy agrarian reforms. Stolypin hoped, through his reforms, to stem peasant unrest by creating a class of market oriented smallholding landowners. He is often cited as one of the last major statesmen of Imperial Russia with a clearly defined political programme and determination to undertake major reforms.

Stolypin was born in Dresden, Saxony, on 14 April 1862. His family was prominent in the Russian aristocracy, and Stolypin was related on his father's side to the poet Mikhail Lermontov. His father was Arkady Dmitrievich Stolypin (1821 – 1899), a Russian landowner, descendant of a great noble family, a general in the Russian artillery and later Commandant of the Kremlin Palace. His mother was Natalia Mikhailovna Stolypina (née Gorchakova; 1827 – 1889), the daughter of the Commanding General of the Russian infantry during the Crimean War and later the Governor General of Warsaw Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov.

From 1869, Stolypin spent his childhood years in Kalnaberžė manor (now Kėdainiai district of Lithuania), built by his father, that remained a favourite residence for the rest of his life. In 1876, the Stolypin family purchased a house in Vilnius for their son to study in the local Gymnasium. He received a good education at St. Petersburg University and began his service in government upon graduation in 1885, when he joined the Ministry of State Property. Four years later Stolypin was elected marshal of the Kovno Governorate. This public service gave him an inside view of the local needs and allowed him to develop administrative skills. He was apparently fascinated by the common lifestyle of Northwestern provinces (especially what is now Lithuania, where his family held estates) with historically dominant privately owned single - family farmsteads and sought ways to transplant it to the rest of the Russian Empire.

In 1884, Stolypin married Olga Borisovna Neidhardt, the daughter of a prominent Russian family, with whom he had five daughters and a son.

In 1902 Stolypin was appointed governor in

Grodno, where he was the youngest person ever appointed to this position. He next became governor of Saratov,

where he became known for the suppression of peasant unrest in 1905,

gaining a reputation as the only governor who was able to keep a firm

hold on his province in this period of widespread revolt. Stolypin was

the first governor to use effective police methods against those who

might be suspected of causing trouble, and some sources suggest that he

had a police record on every adult male in his province. His successes as provincial governor led to Stolypin being appointed interior minister under Ivan Goremykin. A

few months later, Nicholas II appointed Stolypin to replace Goremykin

as Prime Minister. Russia in 1906 was plagued by revolutionary unrest

and wide discontent among the population. Leftist organisations were

waging campaigns against the autocracy, and had wide support;

throughout Russia, police officials and bureaucrats were being

assassinated. To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new

court system that allowed for the arrest and speedy trial of accused

offenders. Over 3,000 suspects were convicted and executed by these

special courts between 1906 - 09. The gallows hence acquired the nickname 'Stolypin's necktie'. He dissolved the First Duma on July 22 [O.S. July 9] 1906, after the reluctance of some of its more radical members to cooperate with the government and calls for land reform. To

help quell dissent, Stolypin also hoped to remove some of the causes of

grievance amongst the peasantry. Thus, he introduced important land

reforms. Stolypin also tried to improve the lives of urban laborers and

worked towards increasing the power of local governments. In

July 1906 he was elected as Prime Minister. He aimed to create a

moderately wealthy class of peasants, who would be supporters of

societal order ("Stolypin's Reform"). Stolypin changed the nature of the Duma to attempt to make it more willing to pass legislation proposed by the government. After dissolving the Second Duma in June 1907 (Coup of June 1907), he changed the weight of votes more in favour of the nobility and wealthy, reducing the value of lower class votes. This

affected the elections to the Third Duma, which returned much more

conservative members, more willing to cooperate with the government. In

the spring of 1911, Stolypin proposed a bill, which was not passed,

prompting his resignation. He proposed spreading the system of zemstvo to

the southwestern provinces of Russia. It was originally slated to pass

with a narrow majority, but Stolypin's political opponents had it

defeated. Afterwards he resigned as Prime Minister of the Third Duma. In

September 1911, Stolypin travelled to Kiev, despite police warnings

that an assassination plot was afoot. He travelled without bodyguards and even refused to wear his bullet proof vest. On September 14 [O.S. September 1] 1911, while he was attending a performance of Rimsky - Korsakov's The Tale of Tsar Saltan at the Kiev Opera House in

the presence of the Tsar and his two eldest daughters, the Grand

Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, Stolypin was shot twice, once in the arm

and once in the chest, by Dmitri Bogrov (born Mordekhai Gershkovich), who was both a leftist radical and an agent of the Okhrana.

Stolypin was reported to have coolly risen from his chair, removed his

gloves and unbuttoned his jacket, exposing a blood soaked waistcoat. He

sank into his chair and shouted 'I am happy to die for the Tsar' before

motioning to the Tsar in his imperial box to withdraw to safety. Tsar

Nicholas remained in his position and in one last theatrical gesture

Stolypin blessed him with a sign of the cross. The next morning the

distressed Tsar knelt at Stolypin's hospital bedside and repeated the

words 'Forgive me'. Stolypin died four days after being shot. Bogrov

was hanged 10 days after the assassination; the judicial

investigation was halted by order of Tsar Nicholas II.

This gave rise to suggestions that the assassination was planned not by

leftists, but by conservative monarchists who were afraid of Stolypin's

reforms and his influence on the Tsar, though this has never been

proven. Stolypin was buried in the Pechersk Monastery (Lavra) in Hyiv, Ukraine. Opinions about Stolypin's work are divided. In the unruly atmosphere after the Russian Revolution of 1905 he

had to suppress violent revolt and anarchy. Historians disagree over

how realistic Stolypin's policies were. The standard view of most

scholars in this field has been that he had little real chance of

reforming agriculture since the Russian peasantry was so backward and

he had so little time to change things. Others however have argued that

while it is true that the conservatism of most peasants prevented them

from embracing progressive change, Stolypin was right in thinking that

he could "wager on the strong" since there was indeed a layer of strong

peasant farmers. This argument is based on evidence drawn from tax

return data, which shows that a significant minority of peasants were

paying increasingly higher taxes from the 1890s, a sign that their

farming was producing higher profits. There remains doubt whether, even without the interuption of Stolypin's murder and the First World War,

his agricultural policy would have succeeded. The deep conservatism

from the mass of peasants made them slow to respond. In 1914 the strip

system was still widespread, with only around 10% of the land having

been consolidated into farms.

Most peasants were unwilling to leave the security of the commune for

the uncertainty of individual farming. Furthermore by 1913 the

government's own Ministry of Agriculture had itself begun to lose

confidence in the policy. After Stolypin's elder brother was killed in a duel,

Stolypin challenged his brother’s duellist. As a result, Stolypin was

wounded in the right arm, which became almost paralysed after the

incident. Stolypin's death was allegedly prophesied by Grigori Rasputin,

who is reported to have shouted, "Death is after him! Death is driving

behind him!" as he ran after the Imperial couple in the crowd outside

the opera house. In a TV poll to select 'the greatest Russian' in 2008, Stolypin placed second. Alexander Nevsky was first; Joseph Stalin came third. He was a keen taxidermist and had one of the largest collections of animals in the world.