<Back to Index>

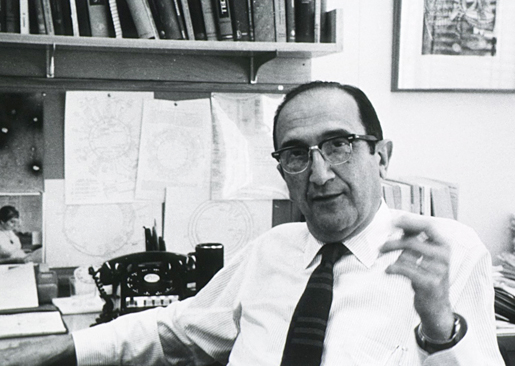

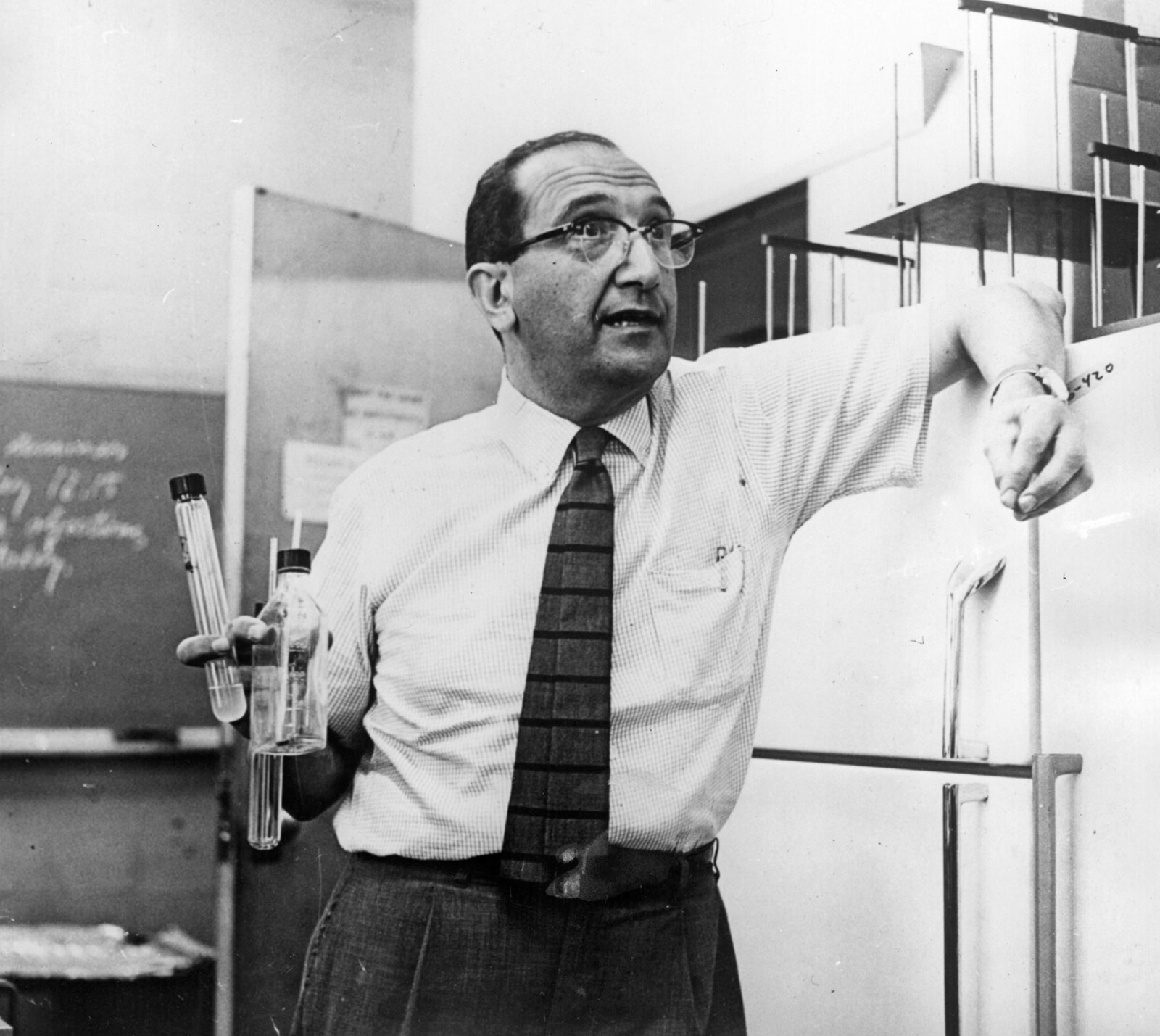

- Microbiologist Salvador Edward Luria, 1912

- Composer Goizueta Francisco Garcia Escudero, 1912

- 1st President of the Republic of Cyprus Makarios III (Michail Christodoulou Mouskos), 1913

PAGE SPONSOR

Salvador Edward Luria (Turin, August 13, 1912 – Lexington, February 6, 1991) was an Italian microbiologist and a Nobel laureate (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) for his pioneering work with Max Delbrück and Alfred Hershey on phages in molecular biology.

Luria was born Salvatore Edoardo Luria in Turin, Italy, to an influential Italian Sephardic Jewish family. He attended the medical school at the University of Turin studying with Giuseppe Levi. There, he met two other future Nobel laureates: Rita Levi - Montalcini and Renato Dulbecco. He graduated from the University of Turin in 1935. From 1936 to 1937, Luria served his required time in the Italian army as a medical officer. He then took classes in radiology at the University of Rome. Here, he was introduced to Max Delbrück's theories on the gene as a molecule and began to formulate methods for testing genetic theory with the bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria.

In 1938, he received a fellowship to study in the United States, where he intended to work with Delbrück. Soon after Luria received the award Benito Mussolini's fascist regime

banned Jews from academic research fellowships. Without funding sources

for work in the U.S. or Italy, Luria left his home country for Paris, France, in 1938. As the Nazi German armies invaded France in 1940, Luria fled on bicycle to Marseilles where he received an immigration visa to the United States. Luria arrived in New York City on September 12, 1940 and soon changed his first and middle names. With the help of physicist Enrico Fermi, whom he knew from his time at the University of Rome, Luria received a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship at Columbia University. He soon met Delbrück and Hershey, and they collaborated on experiments at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and in Delbrück's lab at Vanderbilt University. His famous experiment with Delbrück in 1943, known as the Luria - Delbrück experiment, demonstrated statistically that inheritance in bacteria must follow Darwinian rather than Lamarckian principles and that mutant bacteria

occurring randomly can still bestow viral resistance without the virus

being present. The idea that natural selection affects bacteria has

profound consequences, for example, it explains how bacteria develop antibiotic resistance. From 1943 to 1950, he worked at Indiana University. His first graduate student was James D. Watson, who went on to discover the structure of DNA with Francis Crick. In January 1947, Luria became a naturalized citizen of the United States. In 1950, Luria moved to the University of Illinois at Urbana - Champaign. While investigating how a culture of E. coli was able to stop the production of phages, Luria discovered that specific bacterial strains produce enzymes that cut DNA at certain sequences. These enzymes became known as restriction enzymes and developed into one of the main molecular tools in molecular biology. In 1959, he became chair of Microbiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). At MIT, he switched his research focus from phages to cell membranes and bacteriocins. While on sabbatical in 1963 to study at the Institut Pasteur in

Paris, he found that bacteriocins impair the function of cell

membranes. Returning to MIT, his lab discovered that bacteriocins

achieve this impairment by forming holes in the cell membrane, allowing ions to flow through and destroy the electrochemical gradient of

cells. In 1972, he became chair of The Center for Cancer Research at

MIT. The department he established included future Nobel Prize winners David Baltimore, Susumu Tonegawa, Phillip Allen Sharp and H. Robert Horvitz. In addition to the Nobel Prize, Luria received a number of awards and recognitions. He was named a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1960. From 1968 to 1969, he served as president of the American Society for Microbiology. In 1969, he was awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University together with Max Delbruck co-winner of the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He received the National Book Award in 1974 for his popular science book Life: the Unfinished Experiment. He also received the National Medal of Science in 1991. Throughout his career, Luria was an outspoken political advocate. He joined with Linus Pauling in 1957 to protest the nuclear weapon testing. Luria was an opponent of the Vietnam War and a supporter of organized labor. In the 1970s, he was involved in debates over genetic engineering,

advocating a compromise position of moderate oversight and regulation

rather than the extremes of a complete ban or full scientific freedom.

Due to his political involvement, he was blacklisted from receiving

funding from the National Institutes of Health for a short time in 1969. He died in Lexington, Massachusetts, of a heart attack.