<Back to Index>

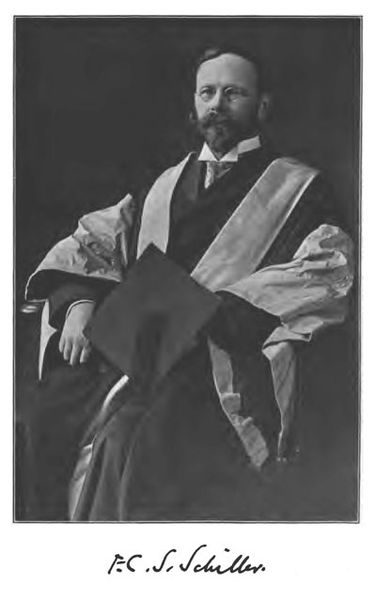

- Philosopher Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller, 1864

- Poet António Pereira Nobre, 1867

- General of the Cavalry Vladimir Aleksandrovich Sukhomlinov, 1848

PAGE SPONSOR

Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller (August 16, 1864 - August 9, 1937) was a German - British philosopher. Born in Altona, Holstein (at that time member of the German Confederation, but under Danish administration), Schiller studied at the University of Oxford, and later was a professor there, after being invited back after a brief time at Cornell University. Later in his life he taught at the University of Southern California. In his lifetime he was well known as a philosopher; after his death his work was largely forgotten.

Schiller's philosophy was very similar to and often aligned with the pragmatism of William James, although Schiller referred to it as "humanism". He argued vigorously against both logical positivism and associated philosophers (for example, Bertrand Russell) as well as absolute idealism (such as F.H. Bradley). Schiller was an early supporter of evolution and a founding member of the English Eugenics Society. Born

in 1864, one of three brothers and the son of Ferdinand Schiller (a

Calcutta merchant), Schiller's family home was in Switzerland. Schiller

was educated at Rugby and Balliol, and graduated in the first class of

Literae Humaniores, winning later the Taylorian scholarship for German

in 1887. Schiller's first book, Riddles of the Sphinx (1891),

was an immediate success despite his use of a pseudonym because of his

fears concerning how the book would be received. Between the years 1893

and 1897 he was an instructor in philosophy at Cornell University. In

1897 he returned to Oxford and became fellow and tutor of Corpus for

more than thirty years. Schiller was president of the Aristotelian

Society in 1921, and was for many years treasurer of the Mind

Association. In 1926 he was elected a fellow of the British Academy. In

1929 he was appointed visiting professor in the University of Southern

California, and spent half of each year in the United States and half

in England. Schiller died in Los Angeles either on August 7 or 9th of

1937 after a long and lingering illness. Schiller was a founding member of the English Eugenics Society and published three books on the subject; Tantalus or the Future of Man (1924), Eugenics and Politics (1926), and Social Decay and Eugenic Reform (1932).

In 1891, F.C.S. Schiller made his first contribution to philosophy anonymously. Schiller feared that in his time of high

naturalism, the metaphysical speculations of his Riddles of the Sphinx were likely to hurt his professional prospects. However, Schiller's fear of reprisal from his anti - metaphysical colleagues should not suggest that Schiller was a friend of metaphysics.

Like his fellow pragmatists across the ocean, Schiller was attempting

to stake out an intermediate position between both the spartan

landscape of naturalism and the speculative excesses of the metaphysics

of his time. In Riddles Schiller both, The result, Schiller contends, is that naturalism cannot make sense of the "higher" aspects of our world (free will, consciousness, God, purpose, universals),

while abstract metaphysics cannot make sense of the "lower" aspects of

our world (the imperfect, change, physicality). In each case we are

unable to guide our moral and epistemological "lower" lives to the achievement of life's "higher" ends, ultimately leading to skepticism on both fronts. For knowledge and

morality to be possible, both the world's lower and higher elements

must be real; e.g. we need universals (a higher) to make knowledge of particulars (a

lower) possible. This would lead Schiller to argue for what he at the

time called a "concrete metaphysics", but would later call "humanism". Shortly

after publishing Riddles of the Sphinx, Schiller became acquainted with

the work of pragmatist philosopher William James and this changed the

course of his career. For a time, Schiller's work became focused on

extending and developing James' pragmatism (under Schiller's preferred

title, "humanism"). Schiller even revised his earlier work Riddles of the Sphinx to

make the nascent pragmatism implicit in that work more explicit. In one

of Schiller's most prominent works during this phase of his career,

“Axioms as Postulates” (1903), Schiller extended James' will to believe

doctrine to show how it could be used to justify not only an acceptance

of God, but also our acceptance of causality, of the uniformity of

nature, of our concept of identity, of contradiction, of the law of

excluded middle, of space and time, of the goodness of God, and more. Towards

the end of his career, Schiller's pragmatism began to take on a

character more unique from the pragmatism of William James. Schiller's

focus became his opposition to formal logic. To understand Shiller's

opposition to formal logic, consider the following inference: From

the formal characteristics of this inference alone (All As are Bs; c is

not a B; Therefore, c is not an A), formal logic would judge this to be

a valid inference. Schiller, however, refused to evaluate the validity

of this inference merely on its formal characteristics. Schiller argued

that unless we look to the contextual fact regarding what specific

problem first prompted this inference to actually occur, we can not

determine whether the inference was successful (i.e. pragmatically

successful). In the case of this inference, since “Cerebos is 'salt'

for culinary, but not for chemical purposes”, without

knowing whether the purpose for this piece of reasoning was culinary or

chemical we cannot determine whether this is valid or not. In another

example, Schiller discusses the truth of formal mathematics "1+1=2" and

points out that this equation does

not hold if one is discussing drops of water. Shiller's attack on

formal logic and formal mathematics never gained much attention from

philosophers, however it does share some weak similarities to the contextualist view in contemporary epistemology as well as the views of ordinary language philosophers. In Riddles, Schiller gives historical examples of the dangers of abstract metaphysics in the philosophies of Plato, Zeno, and Hegel, portraying Hegel as the worst offender: "Hegelianism never anywhere

gets within sight of a fact, or within touch of reality. And the reason

is simple: you cannot, without paying the penalty, substitute

abstractions for realities; the thought - symbol cannot do duty for the

thing symbolized". Schiller

argued that the flaw in Hegel's system, as with all systems of abstract

metaphysics, is that the world it constructs always proves to be

unhelpful in guiding our imperfect, changing, particular, and physical

lives to the achievement of the "higher" universal Ideals and Ends. For

example, Schiller argues that the reality of time and change is intrinsically opposed to the very modus operandi of

all systems of abstract metaphysics. He says that the possibility to

change is a precondition of any moral action (or action generally), and

so any system of abstract metaphysics is bound to lead us into a moral skepticism.

The problem lies in the aim of abstract metaphysics for "interpreting

the world in terms of conceptions, which should be true not here and now, but “eternally”

and independently of Time and Change." The result is that metaphysics

must use conceptions that have the "time - aspect of Reality" abstracted

away. Of course, “[o]nce abstracted from, the

reference to Time could not, of course, be recovered, any more than the

individuality of Reality can be deduced, when once ignored. The

assumption is made that, in order to express the ‘truth’ about Reality,

its ‘thisness,’

individuality, change and its immersion in a certain temporal and

spatial environment may be neglected, and the timeless validity of a

conception is thus substituted for the living, changing and perishing

existence we contemplate. […] What I wish here to point out is merely

that it is unreasonable to expect from such premises to arrive at a deductive justification

of the very characteristics of Reality that have been excluded. The

true reason, then, why Hegelism can give no reason for the

Time - process, i.e. for the fact that the world is ‘in time,’ and

changes continuously, is that it was constructed to give an account of

the world irrespective of time and change. If you insist on having a

system of eternal and immutable ‘truth,’

you can get it only by abstracting from those characteristics of

reality, which we try to express by the terms individuality, time, and

change. But you must pay the price for a formula that will enable you

to make assertions that hold good far beyond the limits of your

experience. And it is part of the price that you will in the end be

unable to give a rational explanation of those very characteristics,

which you dismissed at the outset as irrelevant to a rational

explanation. While abstract metaphysics provides us with a world of beauty and purpose and

various other “highers”, it condemns other key aspects of the world we

live in as imaginary. The world of abstract metaphysics has no place

for imperfect moral agents who (1) strive to learn about the world and

then (2) act upon the world to change it for the better. Consequently,

abstract metaphysics condemns us as illusionary, and declares our place

in the world as unimportant and purposeless. Where abstractions take

priority, our concrete lives collapse into skepticism and pessimism. In

making the case that the naturalist method also results in an

epistemological and moral skepticism, Schiller looks to show this

method’s inadequacy at moving from the cold, lifeless lower world of

atoms to the higher world of ethics, meanings, and minds. As with

abstract metaphysics, Schiller attacks naturalism on many fronts: (1)

the naturalist method is unable to reduce universals to particulars,

(2) the naturalist method is unable to reduce free will to determinist

movements, (3) the naturalist method is unable to reduce emergent properties like consciousness to brain activity, (4) the naturalist method is unable to reduce God into a pantheism,

and so on. Just as the abstract method cannot find a place for the

lower elements of our world inside the higher, the naturalist method

cannot find a place for the higher elements of our world inside the

lower. In a reversal of abstract metaphysics, naturalism denies the

reality of the higher elements to save the lower. Schiller uses the

term “pseudo - metaphysical” here instead of naturalism — as he sometimes

does — because he is accusing these naturalist philosophers of trying to

solve metaphysical problems while sticking to the non-metaphysical

“lower” aspects of the world (i.e. without engaging in real

metaphysics): The

pseudo - metaphysical method puts forward the method of science as the

method of philosophy. But it is doomed to perpetual failure. […] [T]he

data supplied by the physical sciences are intractable, because they

are data of a lower sort than the facts they are to explain. The

objects of the physical sciences form the lower orders in the hierarchy of

existence, more extensive but less significant. Thus the atoms of the

physicist may indeed be found in the organization of conscious beings,

but they are subordinate: a living organism exhibits actions which

cannot be formulated by the laws of physics alone; man is material, but

he is also a great deal more. To

show that the world’s higher elements do not reduce to the lower is not

yet to show that naturalism must condemn the world’s higher elements as

illusionary. A second component to Schiller’s attack is showing that

naturalism cannot escape its inability to reduce the higher to the

lower by asserting that these higher elements evolve from the lower.

However, Schiller does not see naturalism as anymore capable of

explaining the evolution of the higher from the lower than it is

capable of reducing the higher to the lower. While evolution does begin

with something lower that in turn evolves into something higher, the

problem for naturalism is that whatever the starting point for

evolution is, it must first be something with the potential to evolve

into a higher. For example, the world cannot come into existence from

nothing because the potential or “germ” of the world is not “in”

nothing (nothing has no potential, it has nothing; after all, it is

nothing). Likewise, biological evolution cannot begin from inanimate

matter, because the potential for life is not “in” inanimate matter.

The following passage shows Schiller applying the same sort of

reasoning to the evolution of consciousness: Taken

as the type of the pseudo - metaphysical method, which explains the

higher by the lower […] it does not explain the genesis of

consciousness out of unconscious matter, because we cannot, or do not,

attribute potential consciousness to matter. [….] the theory of

Evolution derives the [end result] from its germ, i.e., from that which

was, what it became, potentially. Unable

to either reduce or explain the evolution of the higher elements of our

world, naturalism is left to explain away the higher elements as mere

illusions. In doing this, naturalism condemns us to a skepticism in

both epistemology and ethics. It is worth noting, that while Schiller's

work has been largely neglected since his death, Schiller's arguments

against a naturalistic account of evolution have been recently cited by

advocates of intelligent design to establish the existence of a longer history for the view due to legal concerns in the United States (See: Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District). Schiller

argued that both abstract metaphysics and naturalism portray man as

holding an intolerable position in the world. He proposed a method that

not only recognizes the lower world we interact with, but takes into

account the higher world of purposes, ideals and abstractions. Schiller: We

require, then, a method which combines the excellencies of both the

pseudo - metaphysical and the abstract metaphysical, if philosophy is to

be possible at all. Schiller

was demanding a course correction in the field of metaphysics, putting it

at the service of science. For example, to explain the creation of the

world out of nothing, or to explain the emergence or evolution of the

“higher” parts of the world, Schiller introduces a divine being who

might generate the end (i.e. Final Cause) which gives nothingness, lifelessness, and unconscious matter the purpose (and thus potential) of evolving into higher forms: And thus, so far from dispensing with the need for a Divine First Cause, the theory of evolution,

if only we have the faith in science to carry it to its conclusion, and

the courage to interpret it, proves irrefragably that no evolution was

possible without a pre-existent Deity, and a Deity, moreover,

transcendent, non-material and non-phenomenal. […] [T]he world process

is the working out of an anterior purpose or idea in the divine

consciousness. This re-introduction of teleology (which

Schiller sometimes calls a re-anthropomorphizing of the world) is what

Schiller says the naturalist has become afraid to do. Schiller’s method

of concrete metaphysics (i.e. his humanism) allows for an appeal to

metaphysics when science demands it. However: [T]he

new teleology would not be capricious or random in its application, but

firmly rooted in the conclusions of the sciences [….] The process which

the theory of Evolution divined the history of the world to be, must

have content and meaning determined from the basis of the scientific

data; it is only by a careful study of the history of a thing that we

can determine the direction of its development, [and only then] that we

can be said to have made the first approximation to the knowledge of

the End of the world process. [This]

is teleology of a totally different kind to that which is so

vehemently, and on the whole so justly dreaded by the modern exponents

of natural science. It does not attempt to explain things

anthropocentrically, or regard all creation as existing for the use and

benefit of man; it is as far as the scientist from supposing that

cork - trees grow in order to supply us with champagne corks. The end to

which it supposes all things to subserve is […] the universal End of

the world - process, to which all things tend[.] Schiller finally reveals what this “End” is which “all things tend”: If

our speculations have not entirely missed their mark, the world - process

will come to an end when all the spirits whom it is designed to

harmonize [by its Divine Creator] have been united in a perfect society. Now,

while by today’s philosophic standards Schiller’s speculations would be

considered wildly metaphysical and disconnected from the sciences,

compared with the metaphysicians of his day (Hegel, McTaggart, etc.),

Schiller saw himself as radically scientific. Schiller gave his

philosophy a number of labels during his career. Early on he used the

names "Concrete Metaphysics" and "Anthropomorphism", while later in

life tending towards "Pragmatism" and particularly "Humanism". Schiller

also developed a method of philosophy intended to mix elements of both

naturalism and abstract metaphysics in a way that allows us to avoid

the twin scepticisms each method collapses into when followed on its

own. However, Schiller does not assume that this is enough to justify

his humanism over the other two methods. He accepts the possibility

that both scepticism and pessimism are true. In

order to justify his attempt to occupy the middle ground between

naturalism and abstract metaphysics, Schiller makes a move that anticipates James' The Will to Believe: And

in action especially we are often forced to act upon slight

possibilities. Hence, if it can be shown that our solution is a

possible answer, and the only possible alternative to pessimism, to a

complete despair of life, it would deserve acceptance, even though it

were but a bare possibility. Schiller

contends that in light of the other methods’ failure to provide humans

with a role and place in the universe, we ought avoid the adoption of

these methods. By the end of Riddles,

Schiller offers his method of humanism as the only possible method that

results in a world where we can navigate our lower existence to the

achievement of our higher purpose. He asserts that it is the method we

ought to adopt regardless of the evidence against it (“even though it

were but a bare possibility”). While Schiller’s will to believe is a central theme of Riddle of the Sphinx (appearing

mainly in the introduction and conclusion of his text), in 1891 the

doctrine held a limited role in Schiller's philosophy. In Riddles,

Schiller only employs his version of the will to believe doctrine when

he is faced with overcoming skeptic and pessimistic methods of

philosophy. In 1897, William James published his essay “The Will to

Believe” and this influenced Schiller to drastically expand his

application of the doctrine. For a 1903 volume titled Personal Idealism, Schiller contributed a widely read essay titled “Axioms as Postulates” in which he sets out to justify the “axioms of

logic” as postulates adopted on the basis of the will to believe

doctrine. In this essay Schiller extends the will to believe doctrine

to be the basis of our acceptance of causality, of the uniformity of nature, of our concept of identity, of contradiction, of the law of excluded middle, of space and time, of the goodness of God, and more. He notes that we postulate that nature is uniform because we need nature to be uniform: [O]ut

of the hurly-burly of events in time and space [we] extract[ ]

changeless formulas whose chaste abstraction soars above all reference

to any ‘where’ or ‘when,’ and thereby renders them blank cheques to be

filled up at our pleasure with any figures of the sort. The only

question is — Will Nature honour the cheque? Audentes Natura juvat — let us

take our life in our hands and try! If we fail, our blood will be on

our own hands (or, more probably, in some one else’s stomach), but

though we fail, we are in no worse case than those who dared not

postulate […] Our assumption, therefore, is at least a methodological

necessity; it may turn out to be (or be near) a fundamental fact in

nature [an axiom]. Schiller

stresses that doctrines like the uniformity of nature must first be

postulated on the basis of need (not evidence) and only then “justified

by the evidence of their practical working.” He attacks both

empiricists like John Stuart Mill, who try to conclude that nature is uniform from previous experience, as well as Kantians who

conclude that nature is uniform from the preconditions on our

understanding. Schiller argues that preconditions are not conclusions,

but demands made on our experience that may or may not work. On this

success hinges our continued acceptance of the postulate and its

eventual promotion to axiom status. In “Axioms and Postulates” Schiller vindicates the postulation by its success in practice, marking an important shift from Riddles of a Sphinx. In Riddles,

Schiller is concerned with the vague aim of connecting the “higher” to

the “lower” so he can avoid skepticism, but by 1903 he has clarified

the connection he sees between these two elements. The “higher”

abstract elements are connected to the lower because they are our

inventions for dealing with the lower; their truth depends on their

success as tools. Schiller dates the entry of this element into his

thinking in his 1892 essay “Reality and ‘Idealism’” (a mere year after

his 1891 Riddles). The

plain man’s ‘things,’ the physicist’s ‘atoms,’ and Mr. Ritchie’s

‘Absolute,’ are all of them more or less preserving and well considered

schemes to interpret the primary reality of phenomena, and in this

sense Mr. Ritchie is entitled to call the ‘sunrise’ a theory. But the

chaos of presentations, out of which we have (by criteria ultimately

practical) isolated the phenomena we subsequently call sunrise, is not

a theory, but the fact which has called all theories into being. In

addition to generating hypothetical objects to explain phenomena, the

interpretation of reality by our thought also bestows a derivative

reality on the abstractions with which thought works. If they are the

instruments wherewith thought accomplishes such effects upon reality,

they must surely be themselves real. The shift in Schiller's thinking continues in his next published work, The Metaphysics of the Time - Process (1895):

The abstractions of metaphysics, then, exist as explanations of the

concrete facts of life, and not the latter as illustrations of the

former […] Science [along with humanism] does not refuse to interpret

the symbols with which it operates; on the contrary, it is only their

applicability to the concrete facts originally abstracted from that is

held to justify their use and to establish their ‘truth.’ Schiller's accusations against the metaphysician in Riddles now

appear in a more pragmatic light. His objection is similar to one we

might make against a worker who constructs a flat - head screwdriver to

help him build a home, and who then accuses a screw of unreality when

he comes upon a Phillips - screw that his flat - head screwdriver won’t

fit. In his works after Riddles,

Schiller’s attack takes the form of reminding the abstract

metaphysician that abstractions are meant as tools for dealing with the

“lower” world of particulars and physicality, and that after

constructing abstractions we cannot simply drop the un-abstracted world

out of our account. The un-abstracted world is the entire reason for

making abstractions in the first place. We did not abstract to reach

the unchanging and eternal truths; we abstract to construct an

imperfect and rough tool for dealing with life in our particular and

concrete world. It is the working of the higher in “making predictions

about the future behavior of things for the purpose of shaping the

future behavior of things for the purpose of shaping our own conduct

accordingly” that justifies the higher. To

assert this methodological character of eternal truths is not, of

course, to deny their validity [….] To say that we assume the truth of

abstraction because we wish to attain certain ends, is to subordinate

theoretic ‘truth’ to a teleological implication; to say that, the

assumption once made, its truth is ‘proved’ by its practical working

[….] For the question of the ‘practical’ working of a truth will always

ultimately be found to resolve itself into the question whether we can

live by it. A

few lines down from this passage Schiller adds the following footnote

in a 1903 reprint of the essay: “All this seems a very fairly definite

anticipation of modern pragmatism.” Indeed, it resembles the pragmatist

theory of truth. However, Schiller’s pragmatism was still very

different from both that of William James and that of Charles Sanders Peirce. As early as 1891 Schiller had independently reached a doctrine very similar to William James’ Will to Believe.

As early as 1892 Schiller had independently developed his own

pragmatist theory of truth. However, Schiller's concern with meaning

was one he entirely imports from the pragmatisms of James and Peirce.

Later in life Schiller musters all of these elements of his pragmatism

to make a concerted attack on formal logic. Concerned with bringing

down the timeless, perfect worlds of abstract metaphysics early in

life, the central target of Schiller’s developed pragmatism is the

abstract rules of formal logic. Statements, Schiller contends, cannot

possess meaning or truth abstracted away from their actual use.

Therefore examining their formal features instead of their function in

an actual situation is to make the same mistake the abstract

metaphysician makes. Symbols are meaningless scratches on paper unless

they are given a life in a situation, and meant by someone to

accomplish some task. They are tools for dealing with concrete

situations, and not the proper subjects of study themselves. Both

Schiller’s theory of truth and meaning (i.e. Schiller’s pragmatism)

derive their justification from an examination of thought from what he

calls his humanist viewpoint (his new name for concrete metaphysics).

He informs us that to answer “what precisely is meant by having a

meaning” will require us to “raise the prior question of why we think

at all.”. A question Schiller of course looks to evolution to provide. Schiller

provides a detailed defense of his pragmatist theories of truth and

meaning in a chapter titled “The Biologic of Judgment” in Logic for Use (1929). The account Schiller lays out in many ways resembles some of what Peirce asserts in his "The Fixation of Belief" (1877) essay: Our

account of the function of Judgment in our mental life will, however,

have to start a long way back. For there is much thinking before there

is any judging, and much living before there is any thinking. Even in

highly developed minds judging is a relatively rare incident in

thinking, and thinking in living, an exception rather than the rule,

and a relatively recent acquisition. […] For the most part the living

organism adapts itself to it conditions of life by earlier, easier, and

quicker expedients. Its actions or reactions are mostly ‘reflex

actions’ determined by inherited habits which largely function

automatically […] It follows from this elaborate and admirable

organization of adaptive responses to stimulation that organic life

might proceed without thinking altogether. […] This is, in fact, the

way in which most living being carry on their life, and the plane on

which man also lives most of the time. Thought, therefore, is an

abnormality which springs from a disturbance. Its genesis is connected

with a peculiar deficiency in the life of habit. […] Whenever […] it

becomes biologically important to notice differences in roughly similar

situations, and to adjust action more closely to the peculiarities of a

particular case, the guidance of life by habit, instinct, and impulse

breaks down. A new expedient has somehow to be devised for effecting

such exact and delicate adjustments. This is the raison d’etre of what

is variously denominated ‘thought,’ ‘reason,’ ‘reflection,’

‘reasoning,’ and ‘judgment[.]’ […] Thinking, however, is not so much a

substitute for the earlier processes as a subsidiary addition to them.

It only pays in certain cases, and intelligence may be shown also by

discerning what they are and when it is wiser to act without thinking.

[…] Philosophers, however, have very mistaken ideas about rational

action. They tend to think that men ought to think all the time, and

about all things. But if they did this they would get nothing done, and

shorten their lives without enhancing their merriment. Also they

utterly misconceive the nature of rational action. They represent it as

consisting in the perpetual use of universal rules, whereas it consists

rather in perceiving when a general rule must be set aside in order

that conduct may be adapted to a particular case. This

passage of Schiller was worth quoting at length because of the insight

this chapter offers into Schiller’s philosophy. In the passage,

Schiller makes the claim that thought only occurs when our unthinking

habits prove themselves inadequate for handling a particular situation.

Schiller’s stressing of the genesis of limited occurrences of thought

sets Schiller up for his account of meaning and truth. Schiller

asserts that when a person utters a statement in a situation they are

doing so for a specific purpose: to solve the problem that habit could

not handle alone. The meaning of such a statement is whatever

contribution it makes to accomplishing the purpose of this particular

occurrence of thought. The truth of the statement will be if it helps

accomplishes that purpose. No utterance or thought can be given a

meaning or a truth valuation outside the context of one of these

particular occurrences of thought. This account of Schiller’s is a much

more extreme view than even James took. At

first glance, Schiller appears very similar to James. However,

Schiller’s more stringent requirement that meaningful statements have

consequences “to some one for some purpose” makes Schiller’s position

more extreme than James’. For Schiller, it is not a sufficient

condition for meaningfulness that a statement entail experiential

consequences (as it is for both Peirce and James). Schiller requires

that the consequences of a statement make the statement relevant to

some particular person’s goals at a specific moment in time if it is to

be meaningful. Therefore, it is not simply enough that the statement

“diamonds are hard” and the statement “diamonds are soft” entail

different experiential consequences, it is also required that the

experiential difference makes a difference to someone’s purposes. Only

then, and only to that person, do the two statements state something

different. If the experiential difference between hard and soft

diamonds did not connect up with my purpose for entering into thought,

the two statements would possess the same meaning. For example, if I

were to randomly blurt out “diamonds are hard” and then “diamonds are

soft” to everyone in a coffee shop one day, my words would mean

nothing. Words can only mean something if they are stated with a

specific purpose. Consequently,

Schiller rejects the idea that statements can have meaning or truth

when they are looked upon in the abstract, away from a particular

context. “Diamonds are hard” only possesses meaning when stated (or

believed) at some specific situation, by some specific person, uttered

(or believed) for some specific aim. It is the consequences the

statement holds for that person’s purposes which constitute its

meaning, and its usefulness in accomplishing that person’s purposes

that constitutes the statement’s truth or falsity. After all, when we

look at the sentence “diamonds are hard” in a particular situation we

may find it actually has nothing to say about diamonds. A speaker may

very well be using the sentence as a joke, as a codephrase, or even

simply as an example of a sentence with 15 letters. Which the sentence

really means cannot be determined without the specific purpose a person

might be using the statement for in a specific context. In an article titled “Pragmatism and Pseudo - pragmatism” Schiller defends his pragmatism against a particular counterexample in a way that sheds considerable light on his pragmatism: The

impossibility of answering truly the question whether the 100th (or

10,000th) decimal in the evaluation of Pi is or is not a 9, splendidly

illustrates how impossible it is to predicate truth in abstraction from

actual knowing and actual purpose. For the question cannot be answered

until the decimal is calculated. Until then no one knows what it is, or

rather will turn out to be. And no one will calculate it, until it

serves some purpose to do so, and some one therefore interests himself

in the calculation. And so until then the truth remains uncertain:

there is no 'true' answer, because there is no actual context in which

the question has really been raised. We have merely a number of

conflicting possibilities, not even claims to truth, and there is no

decision. Yet a decision is possible if an experiment is performed. But

his experiment presupposes a desire to know. It will only be made if

the point becomes one which it is practically important to decide.

Normally no doubt it does not become such, because for the actual

purposes of the sciences it makes no difference whether we suppose the

figure to be 9 or something else. I.e. the truth to, say, the 99th

decimal, is ' true enough ' for our purposes, and the 100th is a matter

of indifference. But let that indifference cease, and the question

become important, and the ' truth ' will at once become 'useful '.

Prof. Taylor's illustration therefore conclusively proves that in an

actual context and as an actual question there is no true answer to be

got until the truth has become useful. This point is illustrated also

by the context Prof. Taylor has himself suggested. For he has made the

question about the 100th decimal important by making the refutation of

the whole pragmatist theory of knowledge depend on it. And what nobler

use could the 100th decimal have in his eyes? If in consequence of this

interest he will set himself to work it out, he will discover this once

useless, but now most useful, truth, and — triumphantly refute his own

contention! We

might recognize this claim as the sort of absurdity many philosophers

try to read into the pragmatism of William James. James, however, would

not agree that the meaning of “the 100th decimal of Pi is

9” and “the 100th decimal of Pi is 6” mean the same thing until someone

has a reason to care about any possible difference. Schiller, in

constast, does mean to say this. James and Schiller both treat truth as

something that happens to a statement, and so James would agree that it

only becomes true that the 100th decimal of Pi is 9 when someone in

fact believes that statement and it leads them to their goals, but

nowhere does James imply that meaning is something that happens to a

statement. That is a unique element of Schiller’s pragmatism. While

Schiller felt greatly indebted to the pragmatism of William James,

Schiller was outright hostile to the pragmatism of C.S. Peirce. Both

Schiller and James struggled with what Peirce intended with his

pragmatism, and both were often baffled by Peirce’s insistent rebuffing

of what they both saw as the natural elaboration of the pragmatist

cornerstone he himself first laid down. On the basis of his

misunderstandings, Schiller complains that for Peirce to merely say

“‘truths should have practical consequences’” is to be “very vague, and

hints at no reason for the curious connexion it asserts.” Schiller goes

on to denigrate Peirce’s principle as nothing more than a simple truism

“which hardly deserves a permanent place and name in philosophic

usage”. After all, Schiller points out, “[i]t is hard […] to see why

even the extremest intellectualism should deny that the difference

between the truth and the falsehood of an assertion must show itself in

some visible way.” With

Peirce’s attempts to restrict the use of pragmatism set aside, Schiller

unpacks the term “consequences” to provide what he considers as a more

substantial restatement of Peirce’s pragmatism: For

to say that a [statement] has consequences and that what has none is

meaningless, must surely mean that it has a bearing upon some human

interest; they must be consequences to some one for some purpose. Schiller

believes his pragmatism to be more developed because of its attention

to the fact that the “consequences” which make up the meaning and truth

of a statement, must always be consequences for someone’s particular

purposes at some particular time. Continuing his condemnation of the

abstract, Schiller contends that the meaning of a concept is not the

consequences of some abstract proposition, but what consequences an

actual thinker hopes its use will bring about in an actual situation.

The meaning of a thought is what consequences one means to bring about

when they employ the thought. To Schiller, this is what a more sophisticated pragmatist understands by the term meaning. If

we are to understand the pragmatic theory of meaning in Schiller’s way,

he is right to claim that James’ theory of truth is a mere corollary of

the pragmatist theory of meaning: But

now, we may ask, how are these 'consequences' to test the 'truth'

claimed by the assertion? Only by satisfying or thwarting that purpose,

by forwarding or baffling that interest. If they do the one, the

assertion is 'good' and pro tanto 'true' ;

if they do the other, 'bad' and 'false'. Its 'consequences,' therefore,

when investigated, always turn out to involve the 'practical'

predicates 'good ' or 'bad,' and to contain a reference to ' practice'

in the sense in which we have used that term. So soon as therefore we

go beyond an abstract statement of the narrower pragmatism, and ask

what in the concrete, and in actual knowing, 'having consequences ' may

mean, we develop inevitably the full blown pragmatism in the wider sense. Given

Schiller's view that the meaning of a thought amounts to the

consequences one means to bring about by the thought, Schiller further

concluded that the truth of a thought depends on whether it actually

brings about the consequences one intended. For example, if while

following a cooking recipe that called for salt I were to think to

myself, "Cerebos is salt", my thought will be true if it consequently

leads me to add Cerebos and produce a dish with the intended taste.

However, if while working in a chemistry lab to produce a certain

mixture I were to think to myself, "Cerebos is salt", my thought would

both have a different meaning than before (since my intent now differs)

and be false (since Cerebos is only equivalent to salt for culinary

purposes). According to Schiller, the question of what a thought like

"Cerebos is salt" means or whether it is true can only be answered if

the specific circumstances with which the thought arose are taken into

consideration. While there is some similarity here between Schiller's

view of meaning and the later ordinary language philosophers,

Schiller's account ties meaning and truth more closely to individuals

and their intent with a specific use rather than whole linguistic

communities.