<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller, 1864

- Poet António Pereira Nobre, 1867

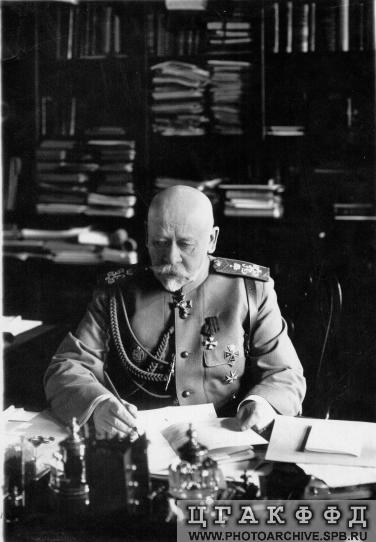

- General of the Cavalry Vladimir Aleksandrovich Sukhomlinov, 1848

PAGE SPONSOR

Vladimir Aleksandrovich Sukhomlinov (Russian: Владимир Александрович Сухомлинов) (August 16 [O.S. August 4] 1848, Kaunas – February 2, 1926, Berlin) was a cavalry general of the Imperial Russian Army (1906) who served as the Chief of the General Staff in 1908 – 09 and the Minister of War until 1915, when he was ousted from office amid allegations of failure to provide necessary armaments and munitions.

Vladimir Sukhomlinov graduated from Nikolayevskoye Cavalry School (1867). He served in Guard Uhlans regiment at Warsaw. He graduated from the General Staff Academy in 1874. He participated in the Russo - Turkish War of 1877 - 1878, served for some time on the staff of Skobelev, and was awarded the Order of St. George 4th class.

After the war, on the invitation of General Mikhail Dragomirov, Chief of the General Staff Academy, he joined the staff of that institution, and lectured as well at the Nicholas Cavalry School, the Corps of Pages and the Mikhail Artillery School.

From 1884 to 1886, Sukhomlinov commanded the 6th Dragoon Regiment at Suvalki. He was Chief of the Officers' Cavalry School at St. Petersburg from 1886 till 1898, being promoted General in 1890. His next appointment was as Commander of the 10th Cavalry Division at Kharkov. In 1899, Sukhomlinov was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kiev Military District. In 1902, he became a deputy commander and, in 1904, commander of the Kiev Military District. In 1905, Vladimir Sukhomlinov was appointed Governor General of Kiev, Podolia, and Volhynia.

In December 1908, he became head of General Staff and, in March 1909, Minister of War. Some regard Vladimir Sukhomlinov as responsible for the military stagnation of 1905 – 1912, which resulted in unpreparedness of the Russian Army at the outbreak of World War I. On the other hand, in Bayonets Before Bullets, Bruce W. Menning asserts that "There was no doubt that he remained committed to building Russia's defensive and offensive military power.... Thanks to Sukhomlinov's reforms, the peacetime strength of the Imperial Russian Army on the eve of World War I reached 1,423,000 officers and men." Though he has some criticism for the Minister, Menning credits him with simplifying and modernizing the structure of the Russian army corps, including the addition of a six-plane detachment to each.

Norman Stone maintains that Sukhomlinov had "an extremely bad press" due to his autocratic style and accusations of corruption made by his enemies in the Duma and the army. The effect of the allegations against him is that "Sukhomlinov, as a sort of uniformed Rasputin, belongs to the demonology of 1917. But the case against him is far from watertight." Stone details his position as leader of informal group of "praetorians" in the high ranks of the army, professional soldiers, often from lower and middle class backgrounds, with experience in and loyalty to the infantry. As such, he and his allies were opposed by what Stone calls the "patrician" faction, upper class officers owing less of their status to military service, who tended to favor the cavalry and artillery (especially fortress artillery). Stone regards the continued standoff between the two factions as the work of the Czar, who played the two sides off against one another as a means of preserving his freedom of action. In any case, Sukhomlinov did try, with some success, to direct resources away from the static fortifications which would prove less useful in the coming war, to the infantry and mobile artillery. His failure to achieve more Stone blames on problems of Russian development economics, and the resistance of the supposedly "technocratic" patrician faction.

As Minister of War, Sukhomlinov was never trusted by the Army Committee of the Duma, led by Alexander Guchkov. Disagreement between the Minister and his assistant, General Alexei Polivanov, culminated in 1912 in the dismissal of Polivanov, and his replacement by General Vernander.

Despite Sukhomlinov's reforms (or perhaps because of his inefficacy and resistance to change, as some assert), the opening phase of the First World War was very bad for Russia. After several defeats of the Russian Army during the first year of war, Vladimir Sukhomlinov was relieved of his post in June 1915.

In March 1916, he was arrested on charges of abuse of power and treason, after some of his close associates had been convicted for espionage on behalf of Germany (S. Myasoyedov, A. Altschuller, V. Dumbadze, and others). After six months in custody, Vladimir Sukhomlinov was placed under house arrest and then once again arrested after the February Revolution of 1917. Trial took place in August and September of 1917, he was sentenced to open - ended katorga on charges of leaving the army unprepared for the Great War.

Sukhomlinov was then sent to a fortress to serve his sentence. On May 1 of 1918, he was released from prison on reaching 70 years of age. Soon, he emigrated to Finland and then to Germany. His memoirs appeared in 1924.