<Back to Index>

- Myrmecologist Horace St. John Kelly Donisthorpe, 1870

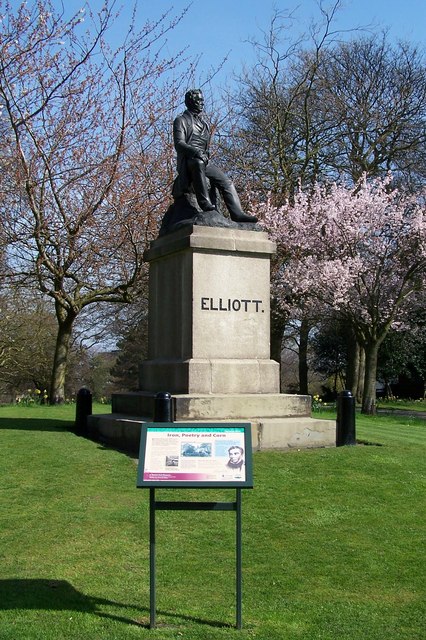

- Poet Ebenezer Elliott, 1781

- 5th Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Roger Brooke Taney, 1777

PAGE SPONSOR

Ebenezer Elliott (17 March 1781 – 1 December 1849) was an English poet, known as the Corn Lawrhymer.

Elliott was born at the New Foundry, Masbrough, in the Parish of Rotherham, Yorkshire. His father, (known as "Devil Elliott", for his fiery sermons) was an extreme Calvinist and a strong Radical, and was engaged in the iron trade. His mother suffered from poor health, and young Ebenezer, although one of a family of eleven children, of whom eight reached mature life, had a solitary and rather morbid childhood. At the age of six he contracted small - pox, which left him ‘fearfully disfigured and six weeks blind.’ His health was permanently affected, and he suffered from illness and depression in later life.

He was first educated at a dame school, then attended the Hollis School in Rotherham, where he was ‘taught to write and little more.’, but was generally regarded as a dunce.

He hated school, and preferred to play truant, spending his time

exploring the countryside around Rotherham, observing the plants and

local wildlife. At about fourteen he began to read extensively on his

own account, and in his leisure hours he studied botany,

collected plants and flowers, and was delighted at the appearance of ‘a

beautiful green snake about a yard long, which on the fine Sabbath

mornings about ten o'clock seemed to expect me at the top of Primrose

Lane.’ When he was sixteen he was sent to work at his father's foundry, working for the next seven years with no wages beyond a little pocket money. In a fragment of autobiography printed in The Athenaeum (12

January 1850) he says that he was entirely self - taught, and

attributes his poetic development to long country walks undertaken in

search of

wild flowers, and to a collection of books, including the works of Young, Barrow, Shenstone and John Milton,

bequeathed to his father. His son - in - law, John Watkins, gave a more

detailed account in "The Life, Poetry and Letters of Ebenezer Elliott",

published 1850. One Sunday morning, after a heavy night’s drinking,

Elliott missed chapel and visited his Aunt Robinson where he picked up a botany book, Sowerby’s “English Botany.” He was entranced by the colour plates of flowers and when she

encouraged him to make his own flower drawings, he was thrilled to find

he had a flair for it. His younger brother, Giles, whom he had always

admired, read him a poem from James Thomson's

“Seasons” which described polyanthus and auricular flowers, and this

was a turning point in Elliott's life. He realised that he could

successfully combine his love of nature, and his talent for drawing,

with writing poems and decorating them with flower illustrations. In 1798, aged seventeen, he wrote his first poem Vernal Walk in imitation of James Thompson. He was also influenced by Byron and the Romantic poets and Robert Southey who later became Poet Laureate.

In 1808 Elliott wrote to Southey asking for advice on getting

published. Elliott was delighted when Southey replied. Their

correspondence over the years encouraged him and reinforced his

determination to make a name for himself as a poet.

Although they only met once, they exchanged letters until 1824, and

Elliott declared that it was Southey who had taught him the art of

poetry. Other early poems were Second Nuptials and Night, or the Legend of Wharncliffe, which last was described by the Monthly Review as the ‘Ne plus ultra of German horror and bombast.’ His Tales of the Night, including The Exile and Bothwell, were

considered to be of more merit, and brought him high commendations. His

earlier volumes of poems, dealing with romantic themes, received much

unfriendly comment, however the faults of Night, the earliest of these, are pointed out in a long and friendly letter (30 January 1819) from Southey to the author. Elliott

married Frances (Fanny) Gartside in 1806, and they had thirteen

children. He invested his wife's fortune in his father's share of the

iron foundry, but the affairs of the family firm were then in a

desperate condition, and money difficulties hastened his father's death. Elliott lost everything, and in 1816 he was declared bankrupt. In 1819 he obtained funds from his wife's sisters and began another business as an iron dealer in Sheffield. The business prospered, and by 1829 he had become a successful iron merchant and steel manufacturer. He remained bitter about his earlier failure. He attributed his father's pecuniary losses and his own to the operation of the Corn Laws and

the demand to repeal them became the greatest issue in his life. When

he was made bankrupt, he had been homeless and out of work; he had

faced starvation and contemplated suicide. He knew what it was like to

be impoverished and desperate and, as a result, he always identified

with the poor. He became well known in Sheffield for

his strident views demanding changes which would improve conditions

both for the manufacturer and the worker. He formed the first society

in England to call for reform of the Corn Laws:

the Sheffield Mechanics' Anti - Bread Tax Society founded in 1830. Four

years later, he was the prime mover in establishing the Sheffield

Anti - Corn Law Society and he also set up the Sheffield Mechanics' Institute. He was very active in the Sheffield Political Union, and he campaigned vigorously for the 1832 Reform Act. He took an active part in the Chartist agitation,

but withdrew his support when the agitation for the repeal of the corn

laws was removed from the Chartist programme. Until the Chartist

Movement advocated the use of violence, Elliott was one of the leaders

of the Sheffield organisation. He was the Sheffield delegate to the

Great Public Meeting in Westminster in 1838 and he chaired the meeting in Sheffield when the Charter was introduced to local people. The

strength of his political convictions was reflected in the style and

tenor of his verse, earning him the nickname " the Corn Law Rhymer", and making him internationally famous. The Corn Law Rhymes, first published in 1831, had been preceded by the publication of the single long poem The Ranter in

1830. They were inspired by a fierce hatred of injustice, and are

vigorous, simple and full of vivid description. The poems campaigned

against the landowners in the government who stifled competition and

kept the price of bread high. They were aggressive and sarcastic,

attacking the status quo and demanding the repeal of the Corn Laws.

They also drew attention to the dreadful conditions endured by working

people, and ruthlessly contrasted their lot with the sleek and

complacent gentry. In 1833 - 1835 Elliott also published The Splendid Village; Corn - Law Rhymes, and other Poems (3 vols.), which included The Village Patriarch (1829), The Ranter, an unsuccessful drama, Keronah, and other pieces. His poems were published in the USA, and in Europe. The French magazine, Le Revue Des Deux Mondes, sent a journalist to Sheffield to interview him. The Corn Law Rhymes were initially thought to be written by an uneducated Sheffield mechanic who

had rejected conventional Romantic ideals for a new style of working

class poetry aimed at changing the system. Elliott was described as "a

red son of the furnace " and called " the Yorkshire Burns"

or " the Burns of the manufacturing city ". The journalist was

surprised when he found Elliott to be a mild man with a nervous

temperament. Asa Briggs called Elliott "the poet of economic revolution" while Elliott himself observed: "I

claim to be a pioneer of the greatest, the most beneficial, the only

crimeless Revolution, which man has yet seen. I also claim to be the

poet of that Revolution - the Bard of Freetrade; and through the prosperity, wisdom and loving - kindness which Free - trade will ultimately bring, the Bard of Universal Peace." He also contributed verses from time to time to Tails Magazine and to the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent.

In 1837 his business failed and he again lost a great deal of money.

This misfortune was also ascribed to the corn laws. He retired in 1841

with a small fortune and settled at Great Houghton, near Barnsley, where he lived quietly until his death in 1849 aged 68. He was buried in Darfield churchyard. (From: the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition) In 1850 appeared two volumes of More Prose and Verse by the Corn - Law Rhymer. Elliott lives by his determined opposition to the bread - tax, as he

called it, and his poems on the subject are saved from the common fate

of political poetry by their transparent sincerity and passionate

earnestness. An article by Thomas Carlyle in the Edinburgh Review (July

1832) is the best criticism on Elliott. Carlyle was attracted by

Elliott's homely sincerity and genuine power, though he had small

opinion of his political philosophy, and lamented his lack of humour

and of the sense of proportion. He thought his poetry too imitative,

detecting not only the truthful severity of Crabbe, but a slight bravura dash of the fair tuneful Hemans. His descriptions of his native county reveal close observation and a vivid perception of natural beauty. His obituary appeared in the Gentleman's Magazine in February 1850. Two biographies were published in 1850, one by his son - in - law, John Watkins, and another by January Searle (G.S. Phillips). A new edition of his works by his son, Edwin Elliot, appeared in 1876. The People's Anthem was one of Elliott’s last poems. It was written for music in 1847, and was usually sung to the tune "Commonwealth". The People’s Anthem first appeared in Tait’s Edinburgh Review in 1848. The refrain “God save the people!” parodies the British national anthem, God Save the Queen and

demands support for ordinary people instead. Despite its huge

popularity, some churches refused to use hymn books which contained it,

as it can also be seen as a criticism of God. In his notes on the poem,

Elliott demanded that the vote be given to all responsible

householders. “The People’s Anthem” was a great favourite for many

years, and in the 1920s it was suggested that Elliott’s poem qualified

him to be designated Poet Laureate of the League of Nations. The People's Anthem Towards

the end of his life, Elliott suffered much pain and depression. His

thoughts often turned to his own death and he wrote his own epitaph: The Poet's Epitaph After his death, John Greenleaf Whittier wrote a poem in his memory, titled Elliott. A bronze statue of Elliott by Neville Northey Burnard,

paid for by the people of Sheffield and Rotherham, was erected in 1854

in Sheffield marketplace at a cost of £600. The statue was moved

to Weston Park, Sheffield, in 1874, where it remains.