<Back to Index>

- Myrmecologist Horace St. John Kelly Donisthorpe, 1870

- Poet Ebenezer Elliott, 1781

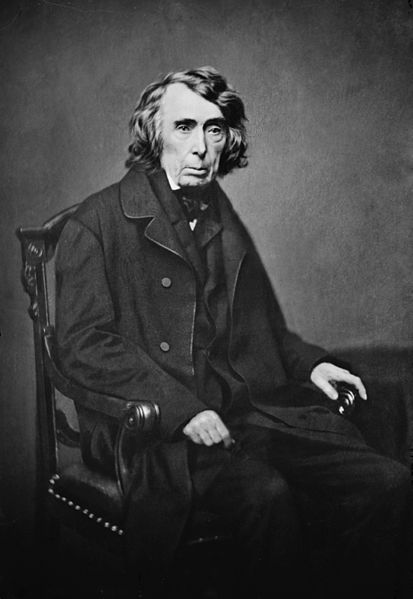

- 5th Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Roger Brooke Taney, 1777

PAGE SPONSOR

Roger Brooke Taney (pronounced /ˈtɔːni/ TAW-nee; March 17, 1777 October 12, 1864) was the fifth Chief Justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. He was the first Roman Catholic to hold that office or sit on the Supreme Court of the United States. He was also the eleventh United States Attorney General. He is most remembered for delivering the majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), that ruled, among other things, that African Americans, having been considered inferior at the time the Constitution was drafted, were not part of the original community of citizens and could not be considered citizens of the United States.

Taney was a Jacksonian Democrat when he became Chief Justice. Described by his and President Andrew Jackson's critics as "[a] supple, cringing tool of Jacksonian power," Taney was a believer in states' rights but also the Union; a slaveholder who regretted the institution and manumitted his slaves. From Prince Frederick, Maryland, he had practiced law and politics simultaneously and succeeded in both. After abandoning Federalism as a losing cause, he rose to the top of the state's Jacksonian machine. As U.S. Attorney General (1831 1833) and then Secretary of the Treasury (1833 1834), Taney became one of Andrew Jackson's closest advisers.

". . . He brought to the Chief Justiceship a high intelligence and legal acumen, kindness and humility, patriotism, and a determination to be a great Chief Justice that enabled him to mold the modest raw material of the Court into an effective and prestigious institution."

Taney died during the final months of the American Civil War on the same day that his home state of Maryland abolished slavery.

Taney was born March 17, 1777. He was the third child and the second son of seven (four sons and three daughters) born to a slaveholding family of tobacco planters in Calvert County, Maryland. He received a rudimentary education from a series of private tutors. After instructing him for a year, his last tutor David English recommended that Taney was ready for college. At the age of 15 he entered Dickinson College, graduating with honors in 1795. As a younger son with no prospect of inheriting the family plantation, Taney chose the profession of law. He read law and in 1799 was admitted to the bar. He quickly distinguished himself as one of Maryland's most promising young lawyers.

Taney married Anne Key on Jan. 7, 1806. They had seven children together.

In 1799, the same year he began practicing as an attorney, Taney was elected to the Maryland state legislature, where he served one term as a Federalist. Returning to private practice, he served as a director of the State Bank Branch in Frederick, Maryland, from 1810 to 1815.

He was elected a state Senator in 1816, serving until 1821 - this time as a Democrat, since the Federalist party had dissolved. He was also a director of the Frederick County Bank from 1818 to 1823, when he returned to private practice. When the 1824 presidential election divided the Democratic Party between supporters and opponents of Andrew Jackson, Taney became a staunch Jacksonian Democrat. He was elected Attorney General of Maryland in 1827, but resigned in 1831, first to serve as acting United States Secretary of War, and then to accept President Jackson's nomination as Attorney General of the United States.

Among Taney's opinions as attorney general, two revealed his stand on slavery: one supported South Carolina's law prohibiting free Blacks from entering the state, and one argued that Blacks could not be citizens. In 1833, as secretary of the Treasury, Taney ordered an end to the deposit of Federal money in the Second Bank of the United States, an act which killed the institution.

Taney was the first nominee to the United States Executive Cabinet to be rejected by the United States Senate when his recess appointment as Secretary of the Treasury failed in a vote of 28 - 18. Rather than return to the position of Attorney General, however, Taney returned to Maryland and resumed private practice.

In January 1835 Jackson, in defiance of the Senate's rejection of Taney as Treasury Secretary, nominated Taney as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court to replace the retiring Gabriel Duvall. The Senate was scheduled to vote on Taney's confirmation on the closing day of the session that month, but the anti - Jackson Whigs who dominated the Senate blocked the vote and introduced a motion to abolish the open seat on the Court. The latter was unsuccessful, but the Whigs succeeded in preventing Taney's confirmation to the Court. (The seat was then left open for over a year until Philip Pendleton Barbour was confirmed to it in 1836.)

Two

factors intervened to help Taney onto the Court, however: after the

1834 elections, Jacksonian Democrats controlled the Senate and, during

the 1835 recess, Chief Justice John Marshall died

following a stage coach accident. On December 28, 1835, Jackson sent

the nomination of Taney as Chief Justice to the Senate, which had

convened that month; after a long and bitter battle with considerable

opposition from Whig leaders Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Jackson's former Vice President John C. Calhoun, Taney was confirmed on March 15, 1836 and received his commission the same day.

Unlike Marshall, who had supported a broad role for the federal government in the area of economic regulation, Taney and the other justices appointed by Jackson more often favored the power of the states. In a series of Commerce Clause cases exemplified by Mayor of the City of New York v. Miln (1837), wherein the challenged New York statute required masters of incoming ships to report information on all passengers they brought into the country, i.e. age, health, last legal residence, etc. The question before the Taney court was whether or not the state statute undercut Congress's authority to regulate commerce; or was it a police measure, as New York claimed, fully within the authority of the state. Taney and his colleagues sought to devise a more nuanced means of accommodating competing federal and state claims of regulatory power. The Court ruled in favor of New York.

The Taney Court also presided over the case of slaves who had taken over the Spanish schooner Amistad. Fellow Justice Joseph Story wrote the Court's decision and opinion. Taney sided with Story's opinion but left no written record of his own in regard to the Amistad case.

In Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, the operators of the Charles River Bridge in Boston sued the operators of a new competing bridge, because the state had granted them a monopoly to collect tolls. Taney argued that, although the Massachusetts legislature had granted the Charles River Bridge a monopoly, the object of the government was to promote general happiness, which took precedence over the rights of monopolies.

In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), the Taney Court agreed to hear a case regarding slavery, slaves, slave owners, and States' Rights. It held that the Constitutional prohibition against state laws that would emancipate any "person held to service or labor in [another] state" barred Pennsylvania from punishing a Maryland man who had seized a former slave and her child, and had taken them back to Maryland without seeking an order from the Pennsylvania courts permitting the abduction. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Joseph Story held not only that states were barred from interfering with enforcement of federal fugitive slave laws, but that they also were barred from assisting in enforcing those laws.

Taney was instrumental in the case of John Merryman, a citizen of the state of Maryland who, in the early years of the American Civil War,

was accused of burning bridges and destroying telegraph poles. He was

seized in his home at 2:00 am by military authorities and taken to Fort

McHenry. His was the first arrest under President Abraham Lincoln's suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus.

In 1857 the Court heard Dred Scott v. Sandford; its decision is considered to have indirectly been a cause of the Civil War. Despite the willingness of five members of the Court to dismiss the lawsuit by Dred Scott, on grounds situated in Missouri law's governing who could sue and be sued, Taney wrote what became regarded as the opinion for the Court. His decision presented his version of the origins of the United States and the Constitution as the basis for his holding that Congress had no authority to restrict the spread of slavery into federal territories, and that such previous attempts to restrict slavery's spread as the 1820 Missouri Compromise were unconstitutional. One of the two dissenters, Justice Benjamin Curtis, was so upset by the decision that he resigned from the court.

The Dred Scott v. Sandford decision was widely condemned at the time by opponents of slavery as an illegitimate use of judicial power. Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party accused the Taney Court of carrying out the orders of the "slave power" and of conspiring with President James Buchanan to undo the Kansas - Nebraska Act. Current scholarship supports that second charge, as it appears that Buchanan put significant political pressure behind the scenes on Justice Robert Grier to obtain at least one vote from a justice from outside the South to support the Court's sweeping decision.

Taney's intemperate language only added to the fury of those who opposed the decision. As he explained the Court's ruling, he noted that African Americans, free or slave, had not been considered part of the original community of people covered by the Constitution, but people of "an inferior order". Because they were originally excluded, he contended that neither the Court nor Congress could now extend rights of citizens to them.

The full text of Taney's statement from the Dred Scott ruling:

uthor Tom Burnam, in Dictionary of Misinformation (1975), commented (pp. 257 58) that "it seems unfair to quote the remark above out of a context which includes the phrase 'that unfortunate race,' etc."

Taney's own attitudes toward slavery were more complex. He emancipated his own slaves and gave pensions to those who were too old to work. In 1819, he defended a Methodist minister who had been indicted for inciting slave insurrections by denouncing slavery in a camp meeting. In his opening argument in that case, Taney condemned slavery as "a blot on our national character."

Taney's attitudes toward slavery appeared to harden in support. By the time he wrote his opinion in Dred Scott, he labeled the opposition to slavery as "northern aggression," a popular phrase among Southerners. He hoped that a Supreme Court decision declaring federal restrictions on slavery in the territories unconstitutional would put the issue beyond the realm of political debate. His decision galvanized Northern opposition to slavery while splitting the Democratic Party on sectional lines.

Many abolitionists and some supporters of slavery believed that Taney was prepared to rule that the states had no power to bar slaveholders from bringing their property into free states, and that laws of free states providing for the emancipation of slaves brought into their territory were unconstitutional. A case, Lemmon v. New York, that presented that issue was slowly making its way to the Supreme Court in the years after the Dred Scott decision. The outbreak of the American Civil War denied Taney the chance to rule on the issue, as the Commonwealth of Virginia seceded and no longer recognized the Court's authority.

Taney personally administered the oath of office to Lincoln, his most prominent critic, on March 4, 1861. He

continued to trouble Lincoln during the three years he remained Chief

Justice after the beginning of the war. After Lincoln suspended the

writ of habeas corpus in parts of Maryland, Taney ruled as Circuit Judge in Ex parte Merryman (1861) that only Congress had the power to take this action. Some scholars argue that Lincoln made an aborted attempt to arrest Taney in response to his habeas corpus decision,

though the evidence is sparse. Lincoln ignored the court's order and

continued to have arrests made without the privilege of the writ.

Merryman was eventually released without charges. Some Radical Republicans in Congress considered initiating impeachment charges against Taney.

Taney, whose health had never been good, spent his final years in worsening health, near poverty, and despised by both North and South. Since the Merryman ruling, he was all but ignored by Lincoln and his cabinet. Taney lost his Maryland estates to the Civil War and suffered from his poverty:

"All my life I have felt the obligation to pay my debts . . . and my inability to do so at this time is mortifying." He explained that his rent had been raised from $4,000 to $8,000 but that he had been prevented from moving to cheaper quarters due to the failing health of his daughter Ellen, who lived with him. The miserable financial situation was maddening to him. . . . A few months later Taney wrote ". . . about peaceful, bygone days . . . walks in the fresh country air. But my walking days are over."

- (Note: Taney's yearly salary was approximately $10,000. In the inflationary Washington, D.C. of this time, the yearly rent for his boarding house rooms had jumped from $4,000 to $8,000, with no increase in pay.)

On October 13, 1864 the clerk of the Supreme Court announced that "the great and good Chief Justice is no more." He had died at the age of eighty - seven the previous evening, having served for more than twenty - eight years as the fifth Chief Justice of the United States.

President Lincoln made no public statement. Of his cabinet, Lincoln and three members Secretary of State William H. Seward, Attorney General Edward Bates, and Postmaster General William Dennison attended Taney's memorial service in Washington, D.C. Only Bates joined the cortθge to Frederick, Maryland, for Taney's funeral and burial. Taney, whose wife had pre-deceased him by nearly twenty years, was survived by two daughters: the sickly Ellen, and a second, widowed daughter with a small child; he left a small life insurance policy and a bundle of worthless Virginia bonds.

Taney

was punished by abolitionists in the Senate after his death. In early

1865, the House of Representatives passed a bill to appropriate funds

for a bust of Taney to be displayed in the Supreme Court. "Now an emancipated country should make a bust to the author of the Dred Scott decision?" exclaimed the indignant Senator Charles Sumner.

"If a man has done evil in his life, he must not be complimented in

marble." Sumner proposed that a vacant spot, not a bust of Taney, be

left in the courtroom "to speak in warning to all who would betray

liberty!"

- His home, Taney Place, located at Adelina, Calvert County, Maryland, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

Taney remained a controversial figure. In 1865, Congress rejected the proposal to commission a bust of Taney to be displayed with those of the four Chief Justices who preceded him. As Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts said:

- I speak what cannot be denied when I declare that the opinion of the Chief Justice in the case of Dred Scott was more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of courts. Judicial baseness reached its lowest point on that occasion. You have not forgotten that terrible decision where a most unrighteous judgment was sustained by a falsification of history. Of course, the Constitution of the United States and every principle of Liberty was falsified, but historical truth was falsified also. . . .

Sumner had long exhibited a bitter dislike of the late Chief Justice. Upon hearing the news of Taney's passing the previous year, he wrote President Abraham Lincoln in celebration declaring that "Providence has given us a victory" in Taney's death.

Notwithstanding, after Taney's successor, Chief Justice Salmon Chase, died, in 1873 Congress approved funds for busts of both Taney and Chase to be displayed in the Capitol alongside the other chief justices.

Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis, author of one of the dissents on Dred Scott, held his former colleague in high esteem despite their differences in that case. Writing in his own memoirs, Curtis described Taney:

- He was indeed a great magistrate, and a man of singular purity of life and character. That there should have been one mistake in a judicial career so long, so exalted, and so useful is only proof of the imperfection of our nature. The reputation of Chief Justice Taney can afford to have anything known that he ever did and still leave a great fund of honor and praise to illustrate his name. If he had never done anything else that was high, heroic, and important, his noble vindication of the writ of habeas corpus, and of the dignity and authority of his office, against a rash minister of state, who, in the pride of a fancied executive power, came near to the commission of a great crime, will command the admiration and gratitude of every lover of constitutional liberty, so long as our institutions shall endure.

Modern legal scholars have tended to concur with Justice Curtis that, despite the Dred Scott decision, Taney was both an outstanding jurist and a competent judicial administrator. His mixed legacy was noted by Justice Antonin Scalia in his dissenting opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey:

There comes vividly to mind a portrait by Emanuel Leutze that hangs in the Harvard Law School: Roger Brooke Taney, painted in 1859, the 82d year of his life, the 24th of his Chief Justiceship, the second after his opinion in Dred Scott. He is all in black, sitting in a shadowed red armchair, left hand resting upon a pad of paper in his lap, right hand hanging limply, almost lifelessly, beside the inner arm of the chair. He sits facing the viewer, and staring straight out. There seems to be on his face, and in his deep set eyes, an expression of profound sadness and disillusionment. Perhaps he always looked that way, even when dwelling upon the happiest of thoughts. But those of us who know how the lustre of his great Chief Justiceship came to be eclipsed by Dred Scott cannot help believing that he had that case -- its already apparent consequences for the Court, and its soon to be played out consequences for the Nation -- burning on his mind.

- Taney County, Missouri, is named in his honor, though it is usually pronounced /ˈteɪni/, not /ˈtɔːni/.

- A statue of Justice Taney is displayed on the grounds of the Maryland State House.

- A street in Baltimore City was named for him.

Chief Justice Taney was the first of the thirteen Catholic justices out of 112 total who have served on the Supreme Court.

- The Treasury - class US Coast Guard Cutter Taney was named for him. The ship is now part of the Baltimore Maritime Museum.

- Liberty ship Roger B. Taney also bore his name. After being commissioned on February 9, 1942, on July 2, 1943 she was torpedoed in the South Atlantic. Three crew members died. Many of the crew were involved in an epic 22 day 2,600 mile journey, including surviving a hurricane, and successfully landing in the Bahamas.