<Back to Index>

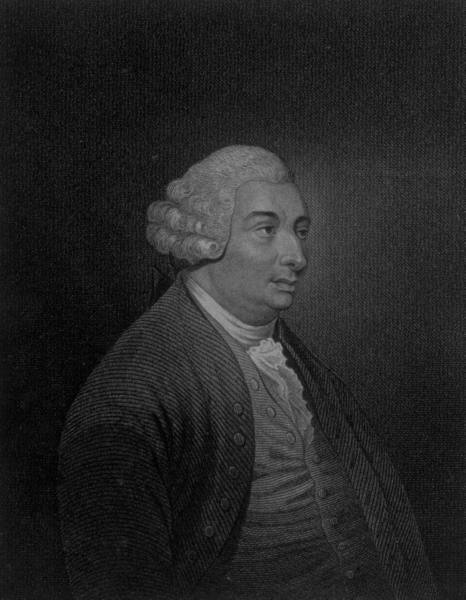

- Philosopher David Hume, 1711

- Writer and Revolutionary Olympe de Gouges, 1748

- King of Joseon Sejong Daewang, 1397

PAGE SPONSOR

David Hume (7 May 1711 [26 April O.S.] – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He is regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment. Hume is often grouped with John Locke, George Berkeley, and a handful of others as a British Empiricist.

Beginning with his A Treatise of Human Nature (1739), Hume strove to create a total naturalistic "science of man" that examined the psychological basis of human nature. In stark opposition to the rationalists who preceded him, most notably Descartes, he concluded that desire rather than reason governed human behaviour, saying famously: "Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions." A prominent figure in the skeptical philosophical tradition and a strong empiricist, he argued against the existence of innate ideas, concluding instead that humans have knowledge only of things they directly experience. Thus he divides perceptions between strong and lively "impressions" or direct sensations and fainter "ideas," which are copied from impressions. He developed the position that mental behaviour is governed by "custom"; our use of induction, for example, is justified only by our idea of the "constant conjunction" of causes and effects. Without direct impressions of a metaphysical "self," he concluded that humans have no actual conception of the self, only of a bundle of sensations associated with the self. Hume advocated a compatibilist theory of free will that proved extremely influential on subsequent moral philosophy. He was also a sentimentalist who held that ethics are based on feelings rather than abstract moral principles. Hume also examined the normative is – ought problem. He held notoriously ambiguous views of Christianity, but famously challenged the argument from design in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779).

Kant credited Hume with waking him up from his "dogmatic slumbers" and Hume has proved extremely influential on subsequent philosophy, especially on utilitarianism, logical positivism, William James, philosophy of science, early analytic philosophy, cognitive philosophy, and other movements and thinkers. The philosopher Jerry Fodor proclaimed Hume's Treatise "the founding document of cognitive science." Also famous as a prose stylist, Hume pioneered the essay as a literary genre and engaged with contemporary intellectual luminaries such as Jean - Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith (who acknowledged Hume's influence on his economics and political philosophy), James Boswell, Joseph Butler, and Thomas Reid.

David Hume, originally David Home, son of Joseph Home of Chirnside, advocate, and Katherine Falconer, was born on 26 April 1711 (Old Style) in a tenement on the north side of the Lawnmarket in Edinburgh. He changed his name in 1734 because the English had

difficulty pronouncing 'Home' in the Scottish manner. Throughout his

life Hume, who never married, spent time occasionally at his family

home at Ninewells by Chirnside, Berwickshire. Hume attended the University of Edinburgh at

the unusually early age of twelve (possibly as young as ten) at a time

when fourteen was normal. At first he considered a career in law, but came to have, in his words, "an insurmountable aversion to everything but the pursuits of Philosophy and general Learning; and while [my family] fanceyed I was poring over Voet and Vinnius, Cicero and Virgil were the Authors which I was secretly devouring". He had little respect for the professors of his time, telling a friend in 1735, "there is nothing to be learnt from a Professor, which is not to be met with in Books". Hume

made a philosophical discovery that opened up to him "... a new Scene of

Thought," which inspired him "...to throw up every other Pleasure or

Business to apply entirely to it." He did not recount what this "Scene" was, and commentators have offered a variety of speculations. Due to this inspiration, Hume set out to spend a minimum of ten years reading and writing. He came to the verge of nervous breakdown, after which he decided to have a more active life to better continue his learning.

As

Hume's options lay between a traveling tutorship and a stool in a

merchant's office, he chose the latter. In 1734, after a few months occupied with commerce in

Bristol, he went to La Flèche in Anjou, France. There he had frequent discourse with the Jesuits of the College of La Flèche. As he had spent most of his savings during his four years there while writing A Treatise of Human Nature, he

resolved "to make a very rigid frugality supply my deficiency of

fortune, to maintain unimpaired my independency, and to regard every

object as contemptible except the improvements of my talents in

literature". He completed the Treatise at the age of 26. Although many scholars today consider the Treatise to be Hume's most important work and one of the most important books in Western philosophy, the critics in Great Britain at the time did not agree, describing it as "abstract and unintelligible". Despite the disappointment, Hume later wrote, "Being naturally of a cheerful and sanguine temper, I soon recovered from the blow and prosecuted with great ardour my studies in the country". There, he wrote the Abstract. Without revealing his authorship, he aimed to make his larger work more intelligible. After the publication of Essays Moral and Political in 1744, Hume applied for the Chair of Pneumatics and Moral Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. However, the position was given to William Cleghorn, after Edinburgh ministers petitioned the town council not to appoint Hume because he was seen as an atheist. During the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion, Hume tutored the Marquis of Annandale (1720 – 92), who was officially described as a "lunatic". This engagement ended in disarray after about a year. But it was then that Hume started his great historical work The History of England,

which took fifteen years and ran over a million words, to be published

in six volumes in the period between 1754 and 1762, while also involved

with the Canongate Theatre. In this context, he associated with Lord Monboddo and other Scottish Enlightenment luminaries in Edinburgh. From 1746, Hume served for three years as Secretary to Lieutenant - General St Clair, and wrote Philosophical Essays Concerning Human Understanding, later published as An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. The Enquiry proved little more successful than theTreatise. Hume was charged with heresy, but he was defended by his young clerical friends, who argued that — as an atheist — he was outside the Church's jurisdiction. Despite his acquittal, Hume failed to gain the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. It was after returning to Edinburgh in 1752, as he wrote in My Own Life,

that "the Faculty of Advocates chose me their Librarian, an office from

which I received little or no emolument, but which gave me the command

of a large library". This resource enabled him to continue historical research for The History of England. Hume achieved great literary fame as a historian. His enormous The History of England, tracing events from the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution of 1688,

was a best seller in its day. In it, Hume presented political man as a

creature of habit, with a disposition to submit quietly to established

government unless confronted by uncertain circumstances. In his view,

only religious difference could deflect men from their everyday lives

to think about political matters. However, Hume's volume of Political Discourses (published by Kincaid & Donaldson, 1752) was the only work he considered successful on first publication.

Hume wrote a great deal on religion. However, the question of what were Hume's personal views on religion is a difficult one. The Church of Scotland seriously considered bringing charges of infidelity against him. He

never declared himself to be an atheist, but had he been hostile to

religion Hume would have been persecuted and his writings constrained,

perhaps the reason behind his ambiguity. He did not acknowledge his

authorship of many of his works in this area until close to his death,

and some were not even published until afterwards. In works such as On Superstition and Enthusiasm,

Hume specifically seems to support the standard religious views of his

time and place. This still meant that he could be very critical of the Catholic Church, referring to it with the standard Protestant epithets and descriptions of it as superstition and idolatry as well as dismissing what his compatriots saw as uncivilised beliefs. He also considered extreme Protestant sects, which he called enthusiasts, to be corrupters of religion. Yet he also put forward arguments that suggested that polytheism had much to commend it in preference to monotheism. In

his works, he attacked many of the basic assumptions of religion and

Christian belief, and his arguments have become the foundation of much

of the succeeding secular thinking about religion. In his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, one of his protagonists challenged one of the intellectual arguments for belief in God or one god (especially in the Age of Enlightenment): the Argument from Design. Also, in his Of Miracles, he challenged the idea that religion (specifically Christianity) is supported by revelation. Nevertheless, he was capable of writing in the introduction to his The Natural History of Religion "The

whole frame of nature bespeaks an intelligent author". In spite of

that, he writes at the end of the essay: "Examine the religious

principles, which have, in fact, prevailed in the world. You will

scarcely be persuaded, that they are anything but sick men's dreams",

and "Doubt, uncertainty, suspence of judgement appear the only result

of our most accurate scrutiny, concerning this subject". It

is likely that Hume was skeptical both about religious belief (at least

as demanded by the religious organisations of his time) and of the

complete atheism promoted by such contemporaries as Baron d'Holbach.

Russell (2008) suggests that perhaps Hume's position is best

characterised by the term "irreligion". O'Connor (2001) writes

that Hume "did not believe in the God of standard theism. ... but he

did not rule out all concepts of deity". Also, "ambiguity suited his

purposes, and this creates difficulty in definitively pinning down his

final position on religion". From 1763 to 1765, Hume was Secretary to Lord Hertford in Paris. He met and later fell out with Jean - Jacques Rousseau. He wrote of his Paris life, "I really wish often for the plain roughness of The Poker Club of Edinburgh ... to correct and qualify so much lusciousness". For a year from 1767, Hume held the appointment of Under Secretary of State for the Northern Department. In 1768, he settled in Edinburgh; he lived from 1771 until his death in 1776 at the southwest corner of St. Andrew's Square, in Edinburgh's New Town, at what is now 21 Saint David Street. (A popular story, consistent with some historical evidence, suggests the street was named after Hume.) James Boswell saw Hume a few weeks before his death (most likely of either bowel or liver cancer). Hume told him he sincerely believed it a "most unreasonable fancy" that there might be life after death. This meeting was dramatized in semi - fictional form for the BBC by Michael Ignatieff as Dialogue in the Dark.

Hume asked that he be interred in a "simple roman tomb"; in his will he

requests that it be inscribed only with his name and the year of his

birth and death, "leaving it to Posterity to add the Rest." It stands, as he wished it, on the southeastern slope of Calton Hill, in the Old Calton Cemetery, not far from his New Town home.