<Back to Index>

- Philosopher David Hume, 1711

- Writer and Revolutionary Olympe de Gouges, 1748

- King of Joseon Sejong Daewang, 1397

PAGE SPONSOR

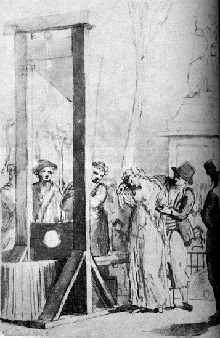

Olympe de Gouges (7 May 1748 – 3 November 1793), born Marie Gouze, was a French playwright and political activist whose feminist and abolitionist writings reached a large audience.

She

began her career as a playwright in the early 1780s. As political

tension rose in France, de Gouges became increasingly politically

involved. She became an outspoken advocate for improving the condition

of slaves in the colonies as of 1788. At the same time, she began

writing political pamphlets. Today she is perhaps best known as an

early feminist who demanded that French women be given the same rights as French men. In her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen (1791), she challenged the practice of male authority and the notion of male - female inequality. She was executed by guillotine during the Reign of Terror for attacking the regime of Maximilien Robespierre and for her close relation with the Girondists. Marie Gouze was born into a petit bourgeois family in 1748 in Montauban, Tarn - et - Garonne, in southwestern France. Her father was a butcher and her mother was the daughter of a cloth merchant. She believed, however, that she was the illegitimate daughter of Jean - Jacques Lefranc, Marquis de Pompignan and his rejection of her claims upon him may have influenced her passionate defense of the rights of illegitimate children. In 1765 she married Louis Aubry, a caterer, who came from Paris with the new Intendant of the town. This was not a marriage of love. Gouze said in a semi - autobiographical novel (Mémoire de Madame de Valmont contre la famille de Flaucourt),

"I was married to a man I did not love and who was neither rich nor

well born. I was sacrificed for no reason that could make up for the

repugnance I felt for this man." Her husband died a year later, and in 1770 she moved to Paris with her son, Pierre, and took the name of Olympe de Gouges. In

1773, according to her biographer Olivier Blanc, she met a wealthy man,

Jacques Biétrix de Rozières, with whom she had a long

relationship that ended during the revolution. She was received in the

artistic and philosophical salons, where she met many writers, including La Harpe, Mercier, and Chamfort as well as future politicians such as Brissot and Condorcet. She usually was invited to the salons of the Marquise de Montesson and the Comtesse de Beauharnais, who also were playwrights. She also was associated with Masonic Lodges among them, the Loge des Neuf Sœurs that was created by her friend Michel de Cubières. Surviving paintings of de Gouges show her to be a woman of beauty. She chose to cohabit with

several men who supported her financially. By 1784 (the year that her

putative biological father died), however, she began to write essays, manifestoes, and socially conscious plays. Seeking upward mobility, she strove to move among the aristocracy and to abandon her provincial accent. In 1784, she wrote the anti - slavery play Zamore and Mirza. For several reasons, the play was not performed until 1789. De Gouges published it, however, as Zamore et Mirza, ou l'heureux naufrage (Zamore and Mirza, or the happy shipwreck) in 1788. It was performed as L'Esclavage des nègres in December of 1789, but shut down after three performances. Subsequently, it was published in 1792 under the title L'Esclavage des noirs. She also wrote on such gender - related topics as the right of divorce and argued in favor of sexual relations outside of marriage. As an epilogue to the 1788 version of her play Zamore et Mirza, she published Réflexions sur les hommes nègres. In 1790, she wrote a play, Le Marché des Noirs (The Black Market) which was rejected by the Comédie Française; the text was burned after her death. In 1808, the Abbé Grégoire included her on his list of the courageous men [sic] who pleaded the cause of "les nègres." A passionate advocate of human rights, Olympe de Gouges greeted the outbreak of the Revolution with hope and joy, but soon became disenchanted when égalité (equal rights) was not extended to women. In 1791, she became part of the Society of the Friends of Truth,

an association with the goal of equal political and legal rights for

women. Also called the "Social Club", members sometimes gathered at the

home of the well known women's rights advocate, Sophie de Condorcet.

Here, De Gouges expressed, for the first time, her famous statement, "A

woman has the right to mount the scaffold. She must possess equally the

right to mount the speaker's platform." That same year, in response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, she wrote the Déclaration des droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne (Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen). This was followed by her Contrat Social (Social Contract, named after a famous work of Jean - Jacques Rousseau), proposing marriage based upon gender equality. She became involved in almost any matter she believed to involve injustice. She opposed the execution of Louis XVI of France,

partly out of opposition to capital punishment and partly because she

preferred a relatively tame and living king to the possibility of a

rebel regency in exile. This earned her the ire of many hard line

republicans, even into the next generation — such as the comment by the

nineteenth century historian Jules Michelet,

a fierce apologist for the Revolution, who wrote, "She allowed herself

to act and write about more than one affair that her weak head did not

understand." Michelet

was also part of a generation of men who opposed any political

participation by women. He disliked de Gouges for this reason.

As the Revolution progressed, she became more and more vehement in her writings. On 2 June 1793, the

Jacobins arrested her allies, the Girondins, and sent them to the guillotine. Finally, her poster Les trois urnes, ou le salut de la Patrie, par un voyageur aérien (The Three Urns, or the Salvation of the Country, By An Aerial Traveler) of 1793, led to her arrest. That piece demanded a plebiscite for a choice among three potential forms of government: the first, indivisible republic, the second, a federalist government, or the third, a constitutional monarchy. She spent three months in jail without an attorney, trying to defend herself. Through her friends she managed to publish two texts: Olympe de Gouges au tribunal révolutionnaire, where she related her interrogations, and the last work, Une patriote persécutée, where she condemned the Terror. The Jacobins, who already had executed a King and Queen,

were in no mood to tolerate any opposition from the intellectuals. De

Gouges was sentenced to death on 2 November 1793, and executed the

following day, for "opposition to the death penalty", a month after Condorcet had been proscribed and several months after the Girondin leaders had been guillotined. Her body was disposed of in the Madeleine Cemetery. After her death, says Olivier Blanc, her son General Pierre Aubry de Gouges went to Guyana with

his wife and five children. He died in 1802, after which his widow

attempted to return to France, but died aboard the ship during her

return. In Guadeloupe,

the two young daughters were married, Marie Hyacinthe Geneviève

de Gouges to an English officer (Captain William Wood), and Charlotte de Gouges to an American politician Robert Selden Garnett, a member of the United States Congress who had plantations in Virginia. Hence, many English and American families have Olympe de Gouges as their ancestor (per Olivier Blanc). On

6 March 2004, the junction of the Rues Béranger, Charlot,

Turenne and Franche - Comté in Paris was proclaimed the Place

Olympe de Gouges. The square was inaugurated by the mayor of the Third

Arrondissement, Pierre Aidenbaum, along with the first deputy mayor of

Paris, Anne Hidalgo. The actress Véronique Genest read an excerpt from the Declaration of the Rights of Woman. 2007 French presidential contender Ségolène Royal has

expressed the wish that the remains of de Gouges be moved to the

Panthéon. However, her remains — as those of the other victims of

the Reign of Terror — have been lost through burial in communal graves,

so any reburial (like that of Condorcet) would be ceremonial. Olympe de Gouges wrote her famous Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen shortly

after the French constitution of 1791 was created in the same year. She

was alarmed that the constitution, which was to promote equal suffrage,

did not address — nor even consider — women’s suffrage. The Constitution

gave that right only to men. It also did not address key issues such as

legal equality in marriage, the right of a woman to divorce her spouse

if he abused her, or a woman’s right to property and custody of the

children. So she created a document that was to be, in her opinion, the

missing part of the Constitution of 1791, in which women would be given

the equal rights they deserve. Throughout the document, it is apparent

to the reader that Gouges had been influenced by the philosophy of the Enlightenment,

whose thinkers, using “scientific reasoning”, critically examined and

criticized the traditional morals and institutions of the day. Gouges

opens up her Declaration with a witty, and at times sarcastically

bitter, introduction in which she asks men why they have chosen to

subjugate women as a lesser sex. Her opening statement put rather

bluntly: “Man, are you capable of being just? It is a woman who poses

the question; you will not deprive her of that right at least.” The

latter part of the statement shows her assertion that men have been

absurdly depriving women of what should be common rights, so she

sarcastically asks if men will find it necessary to take away even her

right to question. Gouges begins her long argument by stating that in nature the

sexes are forever mingled, cooperating in “harmonious togetherness.”

There she uses a bit of Enlightenment logic: if in nature the equality

and the cooperation of the two sexes achieves harmony, so should France

achieve a happier and more stable society if women are given equality

among men. After

her opening paragraph she goes into her declaration, which she asks be

reviewed and decreed by the National Assembly in their next meeting.

Her preamble explains that the reason for contemporary public

misfortune and corrupt government is due to the oppression of women and

their rights. The happiness and well being of society would only be

insured once the rights of women were equally as important as those of

men, especially in political institutions. In her document Gouges

establishes the rights of women on the basis of their equality to men:

that they are both human and capable of the same thoughts. Gouges also

promotes the rights of women by emphasizing differences women have to

men; however, differences that men ought to respect and take notice of.

She argues that women are superior in beauty as well as in courage

during childbirth. Addressing characteristics that set women apart from

men, she adds what she probably thought was logical proof to her

argument that men are not superior to women, and therefore, women are

deserving at least of the same rights. Her

declaration bears the same outline and context as the Declaration of

the Rights of Man and the Citizen, but Gouges either changes the word

“man” to “woman” or adds “for both women and men.” In article II, the

resemblance is exact to the previous declaration except that she adds

“especially” before “the right to the resistance of oppression”,

emphasizing again how important it is to her to end the oppression of

women, and that the government should recognize this and take action. A

main difference between the two declarations is that the Declaration of

the Rights of Man and the Citizen emphasizes the protection of the

written “law” while the Declaration of the Rights of Women and the

Female Citizen emphasizes protection of the “law” and “Natural Laws.”

Gouges emphasizes that these rights of women always have existed, that

they were created at the beginning of time by God, that they are natural and true, and they cannot be oppressed. Article

X contains the famous phrase: “Woman has the right to mount the

scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum.” If

women have the right to be executed, they should have the right to

speak. She

modifies article XI to say that a woman has the right to give her

children the name of their father even if they be out of wedlock or the

father may have left her. Gouges is passionate about this because she

believed that she herself was an illegitimate child. In

her postscript, Gouges exhorts women to wake up and discover that they

have these rights. She assures them that reason is on their side.

Gouges asks, "What have women gained from the French Revolution?" She

states that the answer is nothing, except to be marked with yet more

disdain. She exclaims that women should no longer tolerate this, they

should step up, take action, and demand the equal rights they deserve.

Gouges calls the notion that women are lesser beings an “out - of - date”

concept. In this, she shows strongly her Enlightenment perspective — to

break from old, illogical traditions that are now archaic. She asserts

that to revoke women's right to partake in political life is also

“out - of - date.” Her

last paragraph is titled a "Social Contract between Men and Women."

Taking a leaf from Rousseau’s book, the contract asks for communal

cooperation. The wealth of a husband and wife should be distributed

equally. Property should belong to both and to the children, whatever

bed they come from. If they are divorced, their land should be divided

equally. She called this the “marriage contract.” Gouges also proposed

to allow a poor man’s wife to have her children adopted by a wealthy

family – this would advance the community’s wealth and reduce disorder.

Near the end of the contract, Gouges finally requests creation of a law

to protect widows and girls from men who make false promises. This,

perhaps, is the most important issue she deals with in France. In the

postscript section of her document, Gouges describes the consequences

for a woman who is left by an unfaithful husband, who is widowed with

no fortune to her name, and of young, inexperienced girls who are

seduced by men who leave them with no money and no title for their

children. Gouges therefore demands a law that will force an

unfaithful or unscrupulous man to fulfill his obligations to such a

woman, or to at least to pay a reimbursement equal to his wealth. One

of the last arguments in her document is directed to men who still see

women as lesser beings: “the foolproof way to evaluate the soul of

women is to join them to all the activities of man, if man persists

against this, let him share his fortune with woman by the wisdom of the

laws.” She challenges men that, if they wish, they may evaluate

scientifically the consequences of joining man and woman in equal

political rights. Olympe

de Gouges' bold personality emerges strongly in her writings. She wrote

this declaration in forceful language that was dangerous to use at the

time. Gouges was executed two years later. In the long history of the

struggle for recognition of the rights of women, however, the Gouges

declaration played a very important and positive role.