<Back to Index>

- Physician Marcel Junod, 1904

- Writer Louis Jacques Marie Collin du Bocage (Verneuil), 1893

- Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, 1316

PAGE SPONSOR

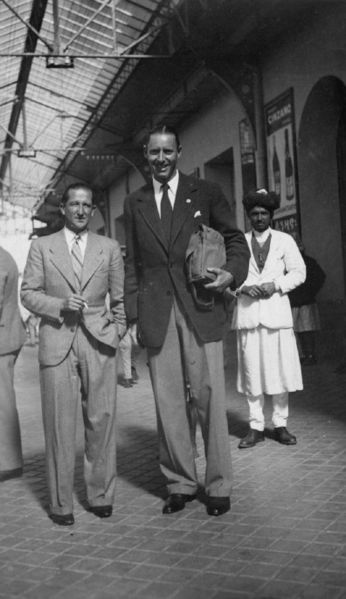

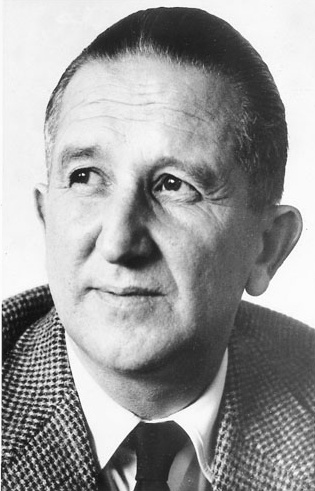

Marcel Junod (May 14, 1904 – June 16, 1961) was a Swiss doctor and one of the most accomplished field delegates in the history of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). After medical school and a short position as a surgeon in Mulhouse, France, he became an ICRC delegate and was deployed in Ethiopia during the Second Italo - Abyssinian War, in Spain during the Spanish Civil War, and in Europe as well as in Japan during World War II. In 1947, he wrote a book with the title Warrior without Weapons about his experiences. After the war, he worked for the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) as chief representative in China, and settled back in Europe in 1950. He founded the anaesthesiology department of the Cantonal Hospital in Geneva and became the first professor in this discipline at the University of Geneva. In 1952, he was appointed a member of the ICRC and, after many more missions for this institution, was Vice - President from 1959 until his death in 1961.

Marcel Junod was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, as the fifth of seven children, to Richard Samuel Junod (1868 – 1919) and Jeanne Marguerite Bonnet (1866 – 1952). His father was a pastor for the Independent Protestant Church of Neuchâtel, first working in mining villages in Belgium and later in poor communities near Neuchâtel and La Chaux - de - Fonds in Switzerland; the latter being where Junod spent most of his childhood. After the death of his father, his family returned to his mother's home of Geneva. A legal rule of the time allowed Junod and his two younger sisters to obtain Genevan citizenship. In order to earn a living, his mother opened a boarding house, together with his aunt.

Junod completed his initial education in 1923 with a baccalaureate diploma from Geneva's Collège Calvin, the same school that Red Cross founder Henry Dunant had

attended. As a student, he volunteered in charity work and directed the

Relief Movement for Russian Children in Geneva. Due to generous

financial support from his uncle Henri - Alexandre Junod he was able to follow his aspirations and study medicine in Geneva and Strasbourg, obtaining his MD in 1929. He opted for special training in the field of surgery and interned at hospitals in Geneva and Mulhouse,

France (1931 – 1935). He completed his training in Mulhouse in 1935, and

began work as the head of the Mulhouse hospital's surgical clinic. Immediately after the Italian invasion of Ethiopia,

Junod received a call on October 15, 1935 from a friend in Geneva

recommending him to take a position as delegate for the International

Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Ethiopia.

Encouraged by the head doctor of the clinic in Mulhouse, he accepted

the offer and soon traveled to Addis Ababa with a second ICRC delegate,

Sidney Brown. He would remain in Ethiopia until the end of the

Abyssinian War in May 1936. Because

of his experience in law, Sidney Brown worked on the establishment of

an effective national Red Cross Society in Ethiopia. Junod focused on

the maintenance and coordination of Red Cross ambulances provided by

the Red Cross societies of Egypt, Finland, the UK, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden.

While the Ethiopian Red Cross, having been founded only shortly before

the outbreak of the war, accepted support from the ICRC and the League

of Red Cross societies, the Italian Red Cross refused any cooperation, as Italy had not accepted the offer of services of the ICRC. Some of the most difficult experiences for Junod during the war involved the attacks on Red Cross ambulances by

the Italian military and Ethiopian armed groups. A bombing of a Swedish

ambulance on December 30, 1935 killed 28 Red Cross workers and patients

and wounded 50. He was also witness to a number of horrific episodes in

this war characterized by the extreme gap in technological capabilities

of the two sides. Among other events, he witnessed the bombardment of

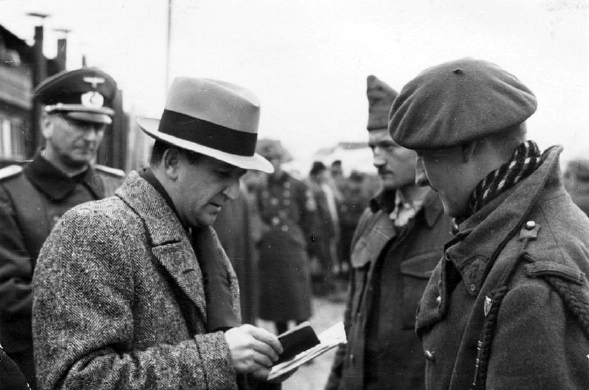

the city Dessie by the Italian air force, the use of mustard gas against civilian populations in the towns of Degehabur and Sassabaneh, and the plundering of Addis Ababa in the final days of the war. In July 1936 the ICRC sought a delegate for an investigation mission to Spain, where civil war had

just broken out. Once again Junod was selected. Contrary to the ICRC's

initial plan of a three week deployment, he ultimately stayed for over

three years, and the ICRC expanded the mission, led by Junod, to nine

delegates spread across the country. The activities of the Red Cross were hindered by the problem that the Geneva Conventions had

no legal application to civil conflicts. As a solution, Junod suggested

the creation of a new combined commission with representatives of the

ICRC and of the warring sides, but the parties could not agree. The

commission would have coordinated work on the release of captured women

and children, the erection of neutral international zones, and the

compilation of prisoner lists. Despite

the ambiguous legal basis for the Red Cross' work in this conflict,

Junod succeeded to convince the warring parties to sign and implement a

number of agreements regarding prisoner exchange and other issues,

thereby saving many lives. Before the fall of Barcelona he

achieved the release of five thousand prisoners whose lives were

endangered by fighting for the city. He also organized research and

information exchange regarding prisoners and missing persons using the

Red Cross card system for the first time in the context of civil

conflict, and by the end of the war the ICRC had facilitated the

exchange of five million cards. The central tasks in this war were the observation of the adherence to the Geneva Conventions in

POW camps and the distribution of provisions and medical supplies to

the civil populations of occupied territories. Yet the civil population

effort was not part of the legally defined role of the ICRC and would

not be so until the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention.

To provide logistical support for these efforts, Junod worked to

introduce the first use of Red Cross ships, specially marked with the

neutral symbols of the ICRC, to provide needed goods and supplies. For

example, a number of ships were provided by Belgium ("Caritas I",

"Caritas II" and "Henri Dunant"), Turkey ("Kurtulus", "Dumlupinar"),

and Sweden ("Hallaren", "Sturebog"). Sadly, on June 9, 1942, despite

its neutral markings, the "Sturebog" was sunk by an Italian aircraft. In

December 1944, Junod married his wife Eugénie Georgette Perret

(1915 - 1970). After a short break from being a delegate, during part of

which he worked in the ICRC headquarters in Geneva, in June 1945 he was

sent to Japan and

arrived in Tokyo on August 9. His original mission involved the visit

of POWs in Japanese camps and the supervision of the adherence to the

Geneva Conventions in Japanese territory. His mission in Japan took

place while his wife was expecting a child at home. After the American dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August

9, 1945) and the subsequent Japanese surrender, Junod organized the

evacuation of POW camps and the Allied rescue of the often severely

injured inmates. On August 30, he received photographic evidence and a

telegraph description of the conditions in Hiroshima. He quickly

organized an assistance mission and on September 8 became the first

foreign doctor to reach the site. He was accompanied by an American

investigation task force, two Japanese doctors, and 15 tons of medical

supplies. He stayed there for five days, during which he visited all of

the major hospitals, administered the distribution of supplies, and

personally gave medical care. The photographs from Hiroshima, which he

gave to the ICRC, were some of the first pictures of the city after the

explosion to reach Europe. His

deployment in Japan and other surrounding Asian countries lasted until

April 1946 when he was able to return to Switzerland, having missed the

birth of his son Benoit in October 1945. After he returned, he wrote

the book "Le Troisième Combattant," entitled in English, "Warrior Without Weapons." It describes, in very personal language, his

experiences during his various ICRC deployments. Other editions were

published in German, in Spanish, Danish, Swedish, Dutch, Japanese and Serbo - Croatian. An Italian translation

of the book appeared in 2006, nearly 60 years later. It has been

reprinted several times by the International Committee of the Red Cross

in English, French and Spanish. The book is sometimes called the

"bedside volume of all young ICRC delegates." From January 1948 until April 1949, Junod was active as a representative of the UN children's help organization, UNICEF, in China, after being invited for that position by then Unicef director Maurice Pate.

However, due to an illness that made it difficult to stand for long

periods of time, he had to cut off his deployment. He also had to turn

down a mission for the World Health Organization (WHO) and was forced to give up his career as a surgeon. He decided to become a specialist in anesthesiology, which would allow him to work sitting down. The need for additional training and education led him to Paris and London,

and in 1951 he returned to Geneva and opened a new practice. For the

first time since his time at the hospital in Mulhouse, he began regular

work once again as a doctor. In 1953, he convinced the management of

the Cantonal Hospital of Geneva to open an anesthesiology department,

of which he later became the director. He was also able to finally

devote himself to medical research, which he presented in numerous

journals and at conferences. Marcel Junod died on June 16, 1961 in Geneva from a massive heart attack while

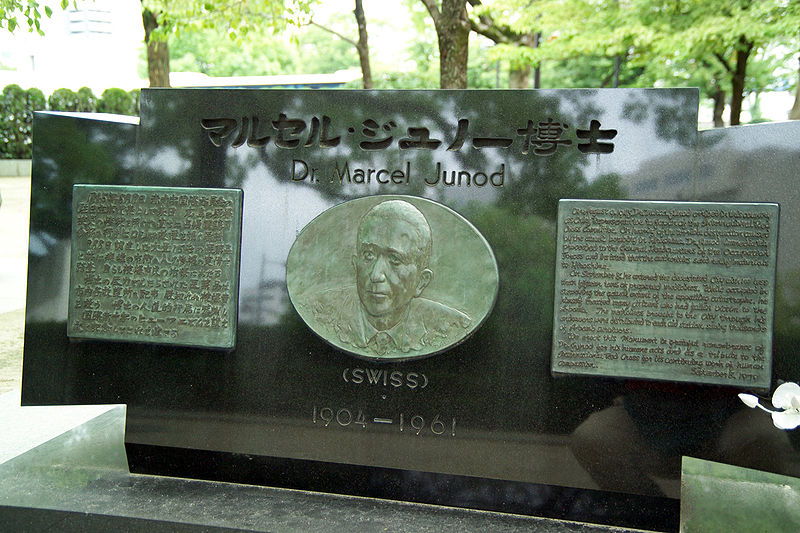

working as an anesthesiologist in an operation. The ICRC received more

than 3,000 letters and other messages of condolence from all over the

world. In the same year, he was posthumously awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure by the government of Japan. On September 8, 1979, a monument to Junod was inaugurated in the Hiroshima Peace Park.

Each year on the anniversary of his death a commemorative meeting is

held in front of the monument. On September 13, 2005, 60 years after he

left Hiroshima, a similar monument was inaugurated in Geneva by the

town and cantonal authorities. The last sentence of the following quote from the final chapter of his book is written on the back of the Hiroshima monument:

In 1946, the USA wanted to honour Junod with the Medal of Liberty for

his work on behalf of Allied prisoners in Japan, but a rule that Swiss

citizens, while bound to military service, cannot accept foreign

decorations, prevented him from receiving it. Four years later in 1950,

he received the Gold Medal for Peace of Prince Carl of Sweden for his

extensive humanitarian service. He was appointed a member of the ICRC

on October 23, 1952 and elected vice - president in 1959. At the

beginning of 1953, he relocated to Lullier,

a small, charming village near Geneva, to find respite from his double

burden as a physician and member of the ICRC. He spent almost all of

his holidays with friends in Barcelona whom he knew from his mission in

Spain. His positions in the ICRC sent him to Budapest, Vienna, Cairo,

and elsewhere. In 1957 he attended the International Red Cross

Conference in New Delhi, and in 1960 he visited national Red Cross

societies in the Soviet Union, Taiwan, Thailand, Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan, Canada, and the United States. In December 1960 he was appointed Professor of Anesthesiology in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Geneva.