<Back to Index>

- Physician Marcel Junod, 1904

- Writer Louis Jacques Marie Collin du Bocage (Verneuil), 1893

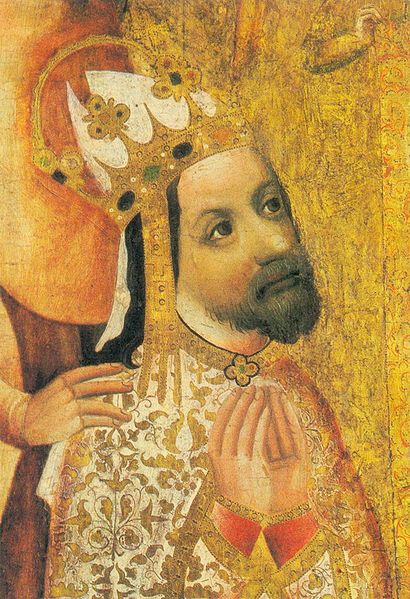

- Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, 1316

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles IV (Czech: Karel IV., German: Karl IV, Latin: Carolus IV) (14 May 1316 – 29 November 1378), born Wenceslaus (Václav), was the second king of Bohemia from the House of Luxembourg, and Holy Roman Emperor.

He was the eldest son and heir of John the Blind, who died (in the Battle of Crécy) on 26 August 1346. Charles inherited the County of Luxembourg and the Kingdom of Bohemia. On 2 September 1347 Charles was crowned King of Bohemia. On 11 July 1346 Prince - electors had elected him King of the Romans (rex Romanorum) in opposition to Emperor Louis IV. Charles was crowned on 26 November 1346 in Bonn.

After his opponent had died, he was re-elected in 1349 (17 June) and

crowned (25 July) King of the Romans. In 1355 he was also crowned King of Italy on 6 January and Holy Roman Emperor on 5 April. With his coronation as King of Burgundy, delayed until 4 June 1365, he became the personal ruler of all the kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire. Born to John and Elisabeth of Bohemia (1292 – 1330) in Prague as Wenceslaus (Václav), the name of her father, but later chose the name Charles at his confirmation after he went to France, at the court of his uncle, Charles IV of France, where he remained for seven years. Charles received French education and was literate and fluent in five languages: Latin, Czech, German, French, and Italian. In 1331 he gained some experience of warfare in Italy with his father. From 1333 he administered the lands of the Bohemian Crown due to his father's frequent absence and later also deteriorating eyesight. In 1334, he was named Margrave of Moravia, the traditional title for the heirs to the throne. Two years later he undertook the government of Tirol on behalf of his brother John Henry, and was soon actively concerned in a struggle for the possession of this county. In consequence of an alliance between his father and Pope Clement VI, the relentless enemy of the emperor Louis IV, Charles was chosen Roman king in opposition to Louis by some of the prince - electors at Rhens on

11 July 1346. As he had previously promised to be subservient to

Clement he made extensive concessions to the Pope in 1347. Confirming

the papacy in the possession of wide territories, he promised to annul

the acts of Louis against Clement, to take no part in Italian affairs,

and to defend and protect the church. Charles

IV was initially in a very weak position in Germany. Owing to the terms

of his election, he was derisively referred to by some as a "priest's

king" (Pfaffenkönig). Many bishops and nearly all of the Imperial

cities remained loyal to Louis the Bavarian. Worse yet, Charles backed

the wrong horse in the Hundred Years' War, losing his father and many of his best knights at the battle of Crecy in August 1346, with Charles himself escaping wounded from the field. Civil

War in Germany was prevented, however, when Louis IV died on 11 October

1347, when he suffered a stroke during a bear hunt. In January 1349 Wittelsbach partisans attempted to secure the election of Günther von Schwarzburg as

king, but he attracted few supporters and died unnoticed and unmourned

after a few months. Thereafter, Charles faced no direct threat to his

claim to the Imperial throne. Charles

initially worked to secure his power base. Bohemia had remained

untouched by the plague. Prague became his capital, and he rebuilt the

city on the model of Paris, establishing the New Town of Prague (Nové Město). In 1348, he founded the University of Prague,

named after him, the first university in Central Europe. This served as

a training ground for bureaucrats and lawyers. Soon Prague emerged as

the intellectual and cultural center of Central Europe. Charles, having made good use of the difficulties of his opponents, was again elected and recrowned at Aachen on 25 July 1349, and was soon the undisputed ruler of the Empire. Gifts or promises had won the support of the Rhenish and Swabian towns; a marriage alliance secured the friendship of the Habsburgs; and that of Rudolf II of Bavaria, count palatine of the Rhine, was obtained when Charles, who had become a widower in 1348, married his daughter Anna. In 1350 the king was visited at Prague by the Roman tribune Cola di Rienzo, who urged him to go to Italy, where the poet Petrarch and the citizens of Florence also implored his presence. Turning a deaf ear to these entreaties, Charles kept Cola in prison for a year, and then handed him as a prisoner to Clement at Avignon. Outside of Prague, Charles attempted to expand the Bohemian crown lands, using his imperial authority to acquire fiefs in Silesia, the Upper Palatinate, and Franconia.

The latter regions comprised "New Bohemia", a string of possessions

intended to link Bohemia with the Luxemburg territories in the

Rhineland. The Bohemian estates were not, however, willing to support

Charles in these ventures. When Charles sought to codify Bohemian law

in the Majestas Carolina of 1355 he met with sharp resistance. After

that point, Charles found it expedient to scale back his efforts at

centralization. In 1354 he crossed the Alps without an army, received the Lombard crown in St. Ambrose Basilica, Milan, on 5 January 1355, and was crowned emperor at Rome by a cardinal in the April of the same year. His

sole object appears to have been to obtain the imperial crown in peace,

and in accordance with a promise previously made to Pope Clement. He

only remained in the city for a few hours, in spite of the expressed

wishes of the Roman people. Having virtually abandoned all the imperial

rights in Italy, the emperor recrossed the Alps, pursued by the

scornful words of Petrarch but laden with considerable wealth. On his return Charles was occupied with the administration of the Empire, then just recovering from the Black Death, and in 1356 he promulgated the famous Golden Bull to regulate the election of the king. Having given Moravia to one brother, John Henry, and erected the county of Luxemburg into a duchy for another, Wenceslaus,

he was unremitting in his efforts to secure other territories as

compensation and to strengthen the Bohemian monarchy. To this end he

purchased part of the upper Palatinate of the Rhine in 1353, and in

1367 annexed Lower Lusatia to Bohemia and bought numerous estates in various parts of Germany. On the death in 1363 of Meinhard, duke of Upper Bavaria and count of Tirol, Upper Bavaria was claimed by the sons of the emperor Louis IV, and Tirol by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria. Both

claims were admitted by Charles on the understanding that if these

families died out both territories should pass to the house of

Luxemburg. About the same time he was promised the succession to the Margravate of Brandenburg,

which he actually obtained for his son Wenceslaus in 1373. He also

gained a considerable portion of Silesian territory, partly by

inheritance through his third wife, Anna von Schweidnitz, daughter of Henry II, Duke of Świdnica. In 1365 Charles visited Pope Urban V at Avignon and undertook to escort him to Rome; and on the same occasion was crowned King of Burgundy at Arles. His second journey to Italy took place in 1368, when he had a meeting with Pope Urban VI at Viterbo, was besieged in his palace at Siena,

and left the country before the end of the year 1369. During his later

years the emperor took little part in German affairs beyond securing

the election of his son Wenceslaus as king of the Romans in 1376, and

negotiating a peace between the Swabian league and some nobles in 1378.

After dividing his lands between his three sons, he died in November

1378 at Prague, where he was buried, and where a statue was erected to his memory in 1848. Charles IV suffered from gout (metabolic arthritis), a painful disease quite common in that time. His

reign was characterised by a transformation in the nature of the Empire

and is remembered as the Golden Age of Bohemia. He promulgated the Golden Bull of 1356 whereby the succession to the imperial title was laid down, which held for the next four centuries. He

also organized the states of the empire into peace keeping

confederations. In these, the Imperial cities figured prominently. The

Swabian Landfriede confederation of 1370 was made up almost entirely of Imperial Cities.

At the same time, the leagues were organized and led by the crown and

its agents. As with the electors, the cities which served in these

leagues were given privileges to aid them in their efforts to keep the

peace. He assured his dominance over the eastern borders of the Empire through succession treaties with the Habsburgs and the purchase of Brandenburg. He also claimed imperial lordship over the crusader states of Prussia and Livonia. He

made Prague the imperial capital, refusing even at the insistence of

Petrarch to move to Rome, and he was a great builder in that city,

which bears his name in so many spots: Charles University, Charles Bridge, and Charles Square. Prague Castle and much of the cathedral of Saint Vitus, by Peter Parler,

were completed under his patronage. Finally, it is from the reign of

Charles that dates the first flowering of manuscript painting in

Prague. In the present Czech Republic, he is still regarded as Pater Patriae (father of the country or otec vlasti), a title first coined by Adalbertus Ranconis de Ericinio at his funeral. Charles IV also had strong ties to Nuremberg,

staying within its city walls 52 times and thereby strengthening its

reputation amongst German cities. Charles was the patron of the Nuremberg Frauenkirche, built between 1352 and 1362 (the architect was likely Peter Parler), where the imperial court worshiped during its stays in Nuremberg. Charles's

imperial policy was focused on the dynastic sphere and abandoned the

lofty ideal of the Empire as a universal monarchy of Christendom. In

1353, he granted Luxembourg to his nephew Jobst.

He concentrated his energies chiefly on the economic and intellectual

development of Bohemia, where he founded the university in 1348 and

encouraged the early humanists.

Indeed, he corresponded with Petrarch, whom he invited to visit his

residence in Prague, but the great Italian hoped — to no avail — to see

Charles move his residence to Rome and reawaken tradition of the Roman Empire. Charles's sister Bona, married the eldest son of Philip VI of France, the future John II of France, in 1335. Thus, Charles was the maternal uncle of Charles V of France, who solicited his relative's advice at Metz in 1356 during the Parisian Revolt.

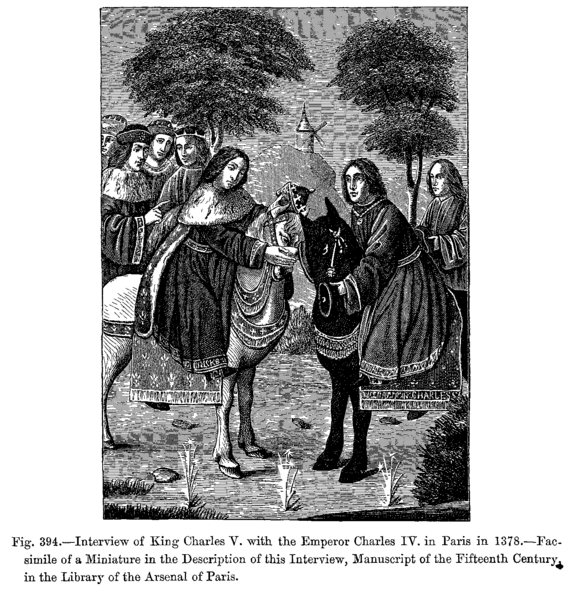

This family connection was celebrated publicly when Charles IV made a

solemn visit to his nephew in 1378, just months before his death. A

detailed account of the occasion, enriched by many splendid miniatures,

can be found in Charles V's copy of the Grandes Chroniques de France.