<Back to Index>

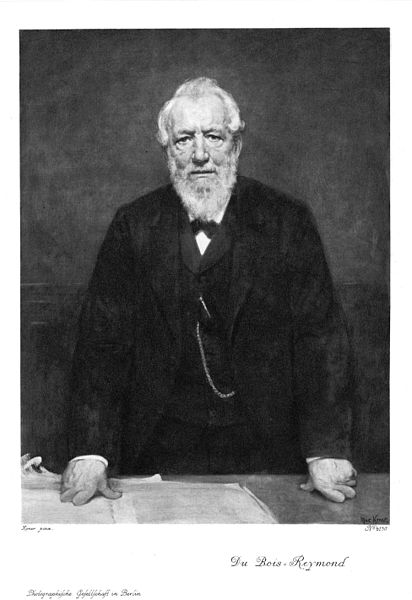

- Physiologist Emil du Bois - Reymond, 1818

- Writer Fritz Reuter, 1810

- Captain of the Royal Navy and Explorer James Cook, 1728

PAGE SPONSOR

Emil du Bois-Reymond (November 7, 1818 – December 26, 1896) was a German physician and physiologist, the discoverer of nerve action potential, and the father of experimental electrophysiology.

Du Bois-Reymond was born in Berlin, and spent his working life there. One of his younger brothers was the mathematician Paul du Bois - Reymond (1831 – 1889). The family was of Huguenot origin.

Educated first at the French College in Berlin, then at Neuchâtel, where his father had returned, Du Bois - Reymond entered in 1836 the University of Berlin. He seems to have been uncertain at first as to the topic of his studies, for he was a student of the renowned ecclesiastical historian August Neander, and dallied with geology, but eventually he began to study medicine, with such zeal and success as to attract the notice of Johannes Peter Müller (1801 – 1858), a well known teacher of anatomy and physiology.

Müller's earlier studies had been distinctly physiological, but his inclination, no less than his position as professor of anatomy as well as of physiology in the University of Berlin, caused him later to study comparative anatomy, and this, aided by his interest in problems of general philosophy, gave his views of physiology a breadth and a depth which influenced the progress of that science in his day profoundly. He had, about the time when the young Du Bois - Reymond came to his lectures, published his Elements of Physiology, the dominant note of which may be said to be this:

"Though there appears to be something in the phenomena of living beings which cannot be explained by ordinary mechanical, physical or chemical laws, much may be so explained, and we may without fear push these explanations as far as we can, so long as we keep to the solid ground of observation and experiment."

Müller recognized in the Neuchâtel a mind fitted to carry on physical researches into the phenomena of living things in

a legitimate way. He made Du Bois - Reymond in 1840 his assistant in

physiology, and as a starting point for an inquiry put into his hands the essay which the Italian Carlo Matteucci, had just published on the electric phenomena of animals. This determined the work of Du Bois - Reymond's life. He chose as the subject of his graduation thesis "Electric fishes," and

so commenced a long series of investigations on bioelectricity, by

which he enriched science and made for himself a name. The results of

these inquiries were made known partly in papers communicated to

scientific journals, but also and chiefly in his work Researches on Animal Electricity, the first part of which appeared in 1848, the last in 1884. It is a record of the exact determination and approximative analysis of the electric phenomena

presented by living beings. Du Bois - Reymond, beginning with the

imperfect observations of Matteucci, built up this branch of science.

He did so by inventing or improving methods, by devising new

instruments of observation or by adapting old ones. On

the other hand, the volumes in question contain an exposition of a

theory. In them Du Bois - Reymond put forward a general conception by the

help of which he strove to explain the phenomena which he had observed.

He developed the view that a living tissue, such as muscle,

might be regarded as composed of a number of "electric molecules", of

molecules having certain electric properties, and that the electric

behaviour of the muscle as a whole in varying circumstances was the

outcome of the behaviour of these native electric molecules. We now know that these are the sodium, potassium and other ions which are responsible for electric membrane phenomena in excitable celles. His theory was soon attacked by several contemporary physiologists, such as Ludimar Hermann, who maintained that a living untouched tissue, such as a muscle,

is not the subject of electric currents so long as it is at rest, it is

isoelectric in substance, and therefore need not be supposed to be made

up of electric molecules, all the electric phenomena which it manifests

being due to internal molecular changes associated with activity or injury.

Du Bois - Reymond's theory was of great value if only as a working

hypothesis, and that as such it greatly helped in the advance of

science. Thus, Du Bois - Reymond's work lay chiefly in the direction of

animal electricity, yet he carried his inquiries — such as could be

studied by physical methods — into other parts of physiology, more

especially into the phenomena of diffusion, though he published little or nothing concerning the results at which he arrived. For

many years, too, Du Bois - Reymond exerted a great influence as a

teacher. In 1858, upon the death of Johannes Müller, the chair of

anatomy and physiology, which that man had held, was divided into a

chair of human and comparative anatomy, which was given to Karl Bogislaus Reichert (1811

– 1883),

and a chair of physiology, which naturally fell to Du Bois - Reymond.

This he held to his death, carrying out his researches for many years

under unfavourable conditions of inadequate accommodation. In 1877,

through his influence, the government provided the university with a

proper physiological laboratory. In 1851 he was admitted into the Academy of Sciences of Berlin, and in 1876 became its perpetual secretary. For many years Du Bois - Reymond and his friend Hermann von Helmholtz, who like him had been a pupil of Johannes Peter Müller, were prominent scientists and professors in the Prussian capital.

Acceptable at court, they both used their position and their influence

for the advancement of science. Du Bois - Reymond, as has been said, had

in his earlier years wandered into fields other than those of

physiology and medicine, and in his later years he went back to some of

these. His gave occasional discourses, dealing with general topics and

various problems of philosophy. Du Bois-Reymond is now remembered also in terms of the ignorabimus, to which he gave common currency. In 1880 Du Bois - Reymond made a famous speech before the Berlin Academy of Sciences outlining

seven "world riddles" some of which, he declared, neither science nor

philosophy could ever explain. He was especially concerned to point out

the limitations of mechanical assumptions about nature in dealing with

certain problems he considered "transcendent". A list of these "riddles": Concerning numbers 1, 2 and 5 he proclaimed: "ignoramus et ignorabimus": "we do not know and will not know."