<Back to Index>

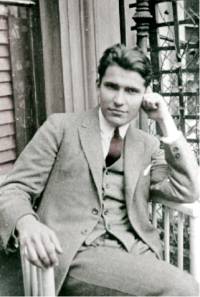

- Biochemist Erwin Chargaff, 1905

- Novelist Charlotte Mary Yonge, 1823

- Regent - Governor of the Kingdom of Hungary John Hunyadi, 1407

PAGE SPONSOR

Erwin Chargaff (Czernowitz, August 11, 1905 – New York City, USA, June 20, 2002) was an American biochemist who emigrated to the United States during the Nazi era. Through careful experimentation, Chargaff discovered two rules that helped lead to the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA.

Chargaff had one son, Thomas, with his wife Vera Broido, whom he married in 1928. Chargaff became an American citizen in 1940. Chargaff was born in Czernowitz on August 11, 1905, Bukowina, Austria, which is now Chernovtsy, Ukraine. Chargaff had a difficult time deciding whether he would pursue science or philology as

a career: he had a natural gift for languages, and over the course of

his life he would learn 15. His American colleagues recalled that he

could speak English better than they could. From 1924 to 1928, Chargaff studied chemistry in Vienna, receiving a doctorate. From 1928 to 1930, Chargaff served as the Milton Campbell Research Fellow in organic chemistry at Yale University, but he did not like New Haven, Connecticut. Chargaff returned to Europe, where he lived from 1930 to 1934, serving first as the assistant in charge of chemistry for the department of bacteriology and public health at the University of Berlin (1930 – 1933),

and then, being forced to resign his position in Germany, as a result

of the Nazi policies, as a research associate at the Pasteur Institute in Paris (1933 – 1934). Chargaff immigrated to New York in 1935, taking a position as a research associate in the department of biochemistry at Columbia University, where he spent most of his professional career. Chargaff became an assistant professor in 1938 and a professor in 1952. After serving as department chair from 1970 to 1974, Chargaff retired to professor emeritus. After his retirement to professor emeritus, Chargaff moved his lab to Roosevelt Hospital, where he continued to work until his retirement in 1992. During his time at Columbia, Chargaff published numerous scientific papers, dealing primarily with the study of nucleic acids such as DNA using chromatographic techniques. He became interested in DNA in 1944 after Oswald Avery identified the molecule as the basis of heredity. In 1950, he discovered that the amounts of adenine and thymine in DNA were roughly the same, as were the amounts of cytosine and guanine. This later became known as the third of Chargaff's rules. Honors awarded to him include the Pasteur Medal (1949) and the National Medal of Science (1974). Erwin Chargaff proposed two main rules in his lifetime which were appropriately named Chargaff's rules. The first and best known achievement was to show that in natural DNA the number of guanine units equals the number of cytosine units and the number of adenine units equals the number of thymine units.

In human DNA, for example, the four bases are present in these

percentages: A=30.9% and T=29.4%; G=19.9% and C=19.8%. This strongly

hinted towards the base pair makeup

of the DNA, although Chargaff did not explicitly state this connection

himself. For this research, Chargaff is credited with disproving the tetranucleotide hypothesis (Phoebus Levene's

widely accepted hypothesis that DNA was composed of a large number of

repeats of GACT). Most researchers had previously assumed that

deviations from equimolar base ratios (G = A = C = T) were due to

experimental error, but Chargaff documented that the variation was real,

with [C + G] typically being slightly less abundant. He was able to do

this with the newly developed paper chromatography and ultraviolet spectrophotometer. Chargaff met Francis Crick and James D. Watson at Cambridge in

1952, and, despite not getting on well with them personally, explained

his findings to them. Chargaff's research would later help the Watson

and Crick laboratory team to deduce the double helical structure of DNA. The

second of Chargaff's rules is that the composition of DNA varies from

one species to another, in particular in the relative amounts of A, G,

T, and C bases. Such evidence of molecular diversity, which had been

presumed absent from DNA, made DNA a more credible candidate for the genetic material than protein. Besides making these important steps toward the structure of DNA, Chargaff's lab also conducted research on the metabolism of amino acids and inositol, blood coagulation, lipids and lipoproteins, and the biosynthesis of phosphotransferases. Beginning in the 1950s, Chargaff became increasingly outspoken about the failure of the field of molecular biology,

claiming that molecular biology was "running riot and doing things that

can never be justified." He believed that human knowledge will always

be limited in relation to the complexity of

the natural world, and that it is simply dangerous when humans believe

that the world is a machine, even assuming that humans can have full knowledge of its workings. He also believed that in a world that functions as a complex system of interdependency and interconnectedness, genetic engineering of

life will inevitably have unforeseen consequences. Chargaff warned that

“the technology of genetic engineering poses a greater threat to the

world than the advent of nuclear technology. An irreversible attack on

the biosphere is something so unheard of, so unthinkable to previous generations, that I only wish that mine had not been guilty of it.” After Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins received the 1962 Nobel Prize for

their work on discovering the double helix of DNA, Chargaff withdrew

from his lab and wrote to scientists all over the world about his

exclusion. Chargaff was a notable exclusion, along with the deceased Rosalind Franklin,

from the 1962 Nobel Prize for DNA discovery. Along with Chargaff, 23

other scientists contributed significantly to the double helix

elucidation and were not rewarded with the Nobel for their work towards the double helix. Thus,

only the people at 'the top of the pyramid' were rewarded for their

genius, but all of those who provided supporting material are well

recognised by their peers, if not the public or the media. However,

these discussions about who gets and who does not get awards is rather

petty, and totally unbecoming of genuinely great minds.