<Back to Index>

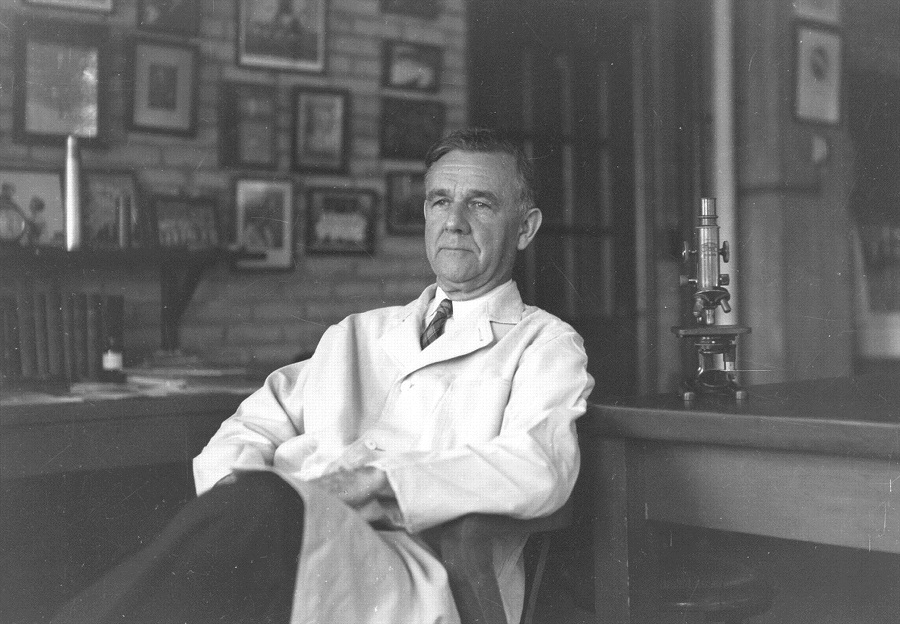

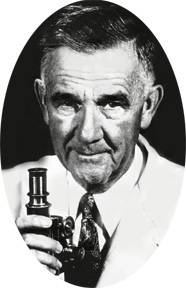

- Pathologist George Hoyt Whipple, 1878

- Composer Peter Winter, 1754

- Minister of Foreign Affairs and 5th Secretary General of NATO Joseph Marie Antoine Hubert Luns, 1911

PAGE SPONSOR

George Hoyt Whipple (August 28, 1878 – February 1, 1976) was an American physician, pathologist, biomedical researcher, and medical school educator and administrator. Whipple shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1934 with George Richards Minot and William Parry Murphy "for their discoveries concerning liver therapy in cases of anemia."

Whipple was born to Ashley Cooper Whipple and Frances Anna Hoyt in Ashland, New Hampshire. He was the son and grandson of physicians. Whipple attended Phillips Academy and then Yale University from which he graduated with a B.A. degree in 1900. He attended medical school at the Johns Hopkins University from which he received the M.D. degree in 1905.

After graduation, Whipple worked in the pathology department at Hopkins until he went to Panama, during the time of the construction of the Panama Canal, as pathologist to the Ancon Hospital in 1907 - 08. Whipple returned to Baltimore, serving successively as Assistant, Instructor, Associate and Associate Professor in Pathology at The Johns Hopkins University between 1910 and 1914.

In 1914, Whipple was appointed Professor of Research Medicine and Director of the Hooper Foundation for Medical Research at the University of California Medical School. He was dean of that medical school in 1920 and 1921.

At the urging of Abraham Flexner, who had done pioneering studies of medical education, and University of Rochester President Rush Rhees, Whipple agreed in 1921 to become Dean of the newly funded and yet - to - be - built medical school in Rochester, New York. Whipple thus became Professor and Chairman of Pathology and the founding Dean of the new School of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Rochester. Whipple served the School as the Dean until 1954 and remained at Rochester for the rest of his life. He was remembered as a superb teacher. Whipple died in 1976 at the age of 97 and is interred in Rochester's Mount Hope Cemetery.

Though he is not related to Allen Whipple, who described the Whipple procedure and Whipple's triad, the two were lifelong friends. Whipple's main research was concerned with anemia and with the physiology and pathology of the liver.

He won the Nobel Prize for his discovery that liver fed to anemic dogs

reverses the effects of the anemia. This remarkable discovery led

directly to successful liver treatment of pernicious anemia by Minot and Murphy. Before that time, pernicious anemia had been truly pernicious in that it was invariably fatal. In presenting the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1934, Professor I. Holmgren of the Nobel committee observed that

"Of the three prize winners, it was Whipple who first occupied himself

with the investigations for which the prize is now awarded. ...

Whipple's experiments were planned exceedingly well, and carried out

very accurately, and consequently their results can lay claim to

absolute reliability. These investigations and results of Whipple's gave

Minot and Murphy the idea that an experiment could be made to see

whether favorable results might also be obtained in the case of pernicious anemia... by

making use of the foods of the kind that Whipple had found to yield

favorable results in his experiments regarding anemia from loss of

blood." Whipple

was also the first person to describe an unknown disease he called

lipodystrophia intestinalis because there were abnormal lipid deposits in the small intestine wall. Whipple also correctly pointed to the bacterial cause of the disease in his original report in 1907. The condition has since come to be called Whipple's disease.