<Back to Index>

- Pathologist George Hoyt Whipple, 1878

- Composer Peter Winter, 1754

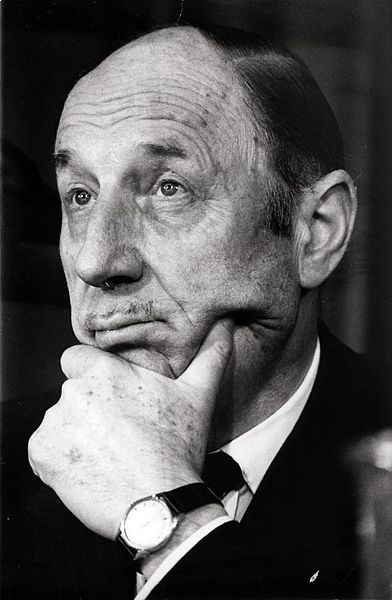

- Minister of Foreign Affairs and 5th Secretary General of NATO Joseph Marie Antoine Hubert Luns, 1911

PAGE SPONSOR

Joseph Marie Antoine Hubert Luns, CH (August 28, 1911 - July 17, 2002) was a Dutch politician and diplomat of the defunct Catholic People's Party (KVP) now merged into the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA). He was the longest serving Minister of Foreign Affairs from September 2, 1952 until July 6, 1971. He served as the 5th Secretary General of NATO for 13 years from October 1, 1971 until June 25, 1984, the longest serving Secretary General of NATO.

Joseph Luns was born in a Roman Catholic, francophile and artistic family. His mother’s family originated from Alsace - Lorraine and had moved to Belgium after the annexation of the region by the German Reich in 1871. His father Huib Luns was a versatile artist and a gifted educationalist, who ended his career as professor of architectural drawing at the Technical University of Delft. Luns got his secondary education in Amsterdam and Brussels. He opted to become a commissioned officer of the Dutch Royal Navy, but registered too late to be selected. Therefore, Luns decided to study law at Amsterdam University during the period 1932 - 1937. Like his father, Luns demonstrated a preference for conservative and authoritarian political parties and an interest in international politics. As a young student he positioned himself on the political right, favoring a strong authority for the state and being of the opinion that socialism, due to its idealistic ideology, had fostered the rising of fascism and nazism. Luns himself had been a silent member of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (NSB), but left in 1936 before this party chose a strongly anti - semitic course.

His choice for a diplomatic career was inspired by his father. He joined the Dutch Diplomatic Service in 1938 and after a two year assignment at the Private Office of the Foreign Minister he was appointed as attaché in Bern (Switzerland) in 1940 and in late 1941 he moved to Lisbon (Portugal). In both countries he was involved in assistance to Dutch refugees, political espionage and counterintelligence. In 1943 he was transferred to the Dutch embassy in London. Ambassador E. Michiels van Verduynen discovered Luns' great affinity for the political element in international affairs and entrusted him with important files on Germany which Luns handled with great skill.

In 1949 Luns was appointed as deputy Dutch permanent representative to the United Nations.

He worked closely with his new chief D. Von Balluseck, a political

appointee without diplomatic experience. After the Netherlands became a

member of the Security Council he temporarily chaired the Disarmament

Commission. Luns was sceptical of the importance of the United Nations

for international peace, believing it at times to be more like a forum

for propaganda than a center for solving international conflicts.

Still, he was of opinion that it was worthwhile to keep the UN in shape

because it was the sole international organisation which offered

opportunities for discussions between all states. Due to the tenacity of the Dutch Catholic People's Party to

occupy the Foreign Ministry after the 1952 elections, Luns entered

Dutch politics as the favorite of its political leader Romme. His

co-Minister was J.W. Beyen,

an international banker, not affiliated to any political party, but

protégé of Queen Juliana. The two ministers had a

completely different style of operating and clashed even before the end

of 1952. However, they accommodated and avoided future conflicts by a

very strict division of labour. Luns was responsible for bilateral

relations, Benelux and international organisations. After the 1956

elections Beyen left office and Luns stayed as Foreign Minister until

1971 in both center - left and center - right governments. Bilateral

relations with Indonesia and the German Federal Republic, security

policy and European integration were the most important issues during

his tenure. Atlantic

cooperation was a fundamental aspect of Luns’ foreign policy, and Dutch

foreign policy in general. In the opinion of Luns, Western Europe could

not survive the Cold War without

American nucleair security and he therefore promoted strong and

intensified political and military cooperation in NATO. Luns accepted

American leadership of the Atlantic Alliance as such but expected better

cooperation between the United States and its allies, since, in Luns’

opinion, the former too often acted independently of its allies,

particularly in decolonisation issues. Although

a great supporter of Atlantic cooperation, Luns could also be critical

of U.S. foreign policy and in bilateral relations he defended Dutch

national interests strongly, as well as expecting American support in

the bilateral difficulties with Indonesia. In 1952 Luns expected to improve relations with Indonesia without transferring the disputed area of West New Guinea to

the former colony. By 1956 however, this policy had proved ineffectual,

while Luns and the Dutch government were still determined not to

transfer West New Guinea to the Republic of Indonesia.

When in 1960 it became obvious that allied support for this policy,

particularly from the United States, was waning, Luns tried to find an

intermediate solution by transferring the administration of the

territory to the United Nations, yet this attempt to keep West New

Guinea out of Indonesian hands failed as well. After difficult

negotiations the area was finally transferred to the Republic of

Indonesia in 1963 after a short interim administration of the UN.

Despite his personal anger over this outcome, which was considered a

personal defeat by Luns, the foreign minister nevertheless worked to

restore relations with Indonesia in the aftermath of the West New

Guinea problem. A visit by Indonesian president Sukarno to the Netherlands was however prevented; Luns regarded Sukarno as an unreliable dictator. Luns was more successful in the normalisation of the bilateral relations with the Federal Republic of Germany.

Luns shared Dutch public opinion in demanding that Germany recognize

the damage it had caused during the Second World War, furthermore a mea

culpa required. He demanded that, before any negotiations on other

bilateral disputes could start, the amount of damages to be paid to

Dutch war victims would be agreed upon. During the final stages of the

negatotiations on bilateral disputes between the two countries, Luns

decided to come to an arrangement with his German colleague on his own

accord. He made concessions and because of this the Dutch parliament

threatened not to ratify the agreement. With the full support of the government however, Luns was able to overcome the crisis. European integration was permanently on Luns’ political agenda. Beyen had introduced the concept of the European Economic Community. In March 1957 Luns signed the Treaties of Rome establishing the EEC and Euratom.

Although he preferred integration of a wider group of European states

he accepted the group of Six of the EEC and defended the supranational

structure it was based on. The endeavours of French president Charles de Gaulle to

subordinate the institutions of the Six to a intergovernmental

political structure, could count on strong opposition from Luns: such

plans would, in his view, only serve French ambitions of a Europe

independent of the United States. Initially

Luns stood alone and he was afraid that French - German cooperation

would result in anti - Atlantic and anti - American policies which

harmed the interests of the West. He made British membership of the

European institutions conditional for his political cooperation.

Gradually his views on Gaullist foreign policies were shared by the

other EEC members and they joined Luns in his objections. Two of De

Gaulle’s decisions stiffened the opposition: first, his denial of EEC

membership to the United Kingdom in January 1963; secondly, France’s

retreat from the integrated military structure of NATO in 1966. Luns

played a vital role in the negotiations unwinding French participation

and continuing its political membership of the Alliance. By that time

Luns had internationally established his reputation as an able and

reliable negotiator and was seen as an important asset in London and

Washington. After the retreat of De Gaulle in 1968, the EEC Summit of

The Hague in December 1969 ended the long crisis of the EEC integration

process, opened the way to British membership and agreed on new venues

for political cooperation, a common market and monetary union. Throughout

his years as Dutch foreign minister, Luns had gained an international

status uncommon for a foreign minister of a small country. He owed this

to his personal style in which duress, a high level of information,

political leniency and diplomatic skills were combined with wit, galant

conversation and the understanding that diplomacy was a permanent

process of negotiations in which a victory should never be celebrated

too exuberantly at the cost of the loser. In 1971, Luns was appointed as NATO Secretary - General.

At the time of his appointment, public protests against American

policies in Vietnam were vehement throughout Western Europe and among

European politicians the credibility of the American nuclear protection

was in doubt. Though there were initial doubts about Luns’ skills for

the job he soon proved that he was capable of managing the alliance in

crisis. He regarded himself as the spokesman of the alliance and he

aimed at balancing the security and political interests of the alliance

as a whole. Luns was in favor of negotitiating with the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact members

on the reduction of armaments, on the condition that the Western

defense was kept in shape during such negotiations. European members of

NATO, according to Luns, should understand that the United States

carried international responsibilities while the latter should

understand that in-depth consultation with the European governments was

conditional to forging a united front on the international stage, which

could be accepted and endorsed by all members of NATO. U.S. - Soviet

negotiations on mutual troop reductions and the strategic nuclear

arsenal caused severe tensions. Luns convinced American leaders that it

undermined the credibility in Western Europe of their nuclear strategy

by neglecting European fears of a change of strategy which would leave

Europe unprotected in case of a Soviet nuclear attack. The modernization

of the tactical nuclear forces by

the introduction of the neutron bomb and cruise missiles caused deep

divisions. In the end Luns succeeded in keeping NATO together in the so

called Double - Track Decision of December 1979. The deployment of these new weapon systems was linked to success in American - Soviet arms reduction talks. It

was also the duty of the Secretary-General to mediate in cause of

conflicts within the alliance. He was successful in the conflict between

Great Britain and Iceland, the so-called Second Cod War,

not by pressuring the Icelandic government to end its aggressive

behaviour against British trawlers, but by convincing the British

government that it had to take the first step by calling back its

destroyers in order to open the way to negotiations. Luns failed however

in the conflict between Greece and Turkey over the territorial

boundaries and Cyprus. Due to lack of cooperation on both sides Luns was

unable to mediate or advice on procedures to find a way out. Luns

retired as Secretary - General in 1984, staying in office for a full 13

years. Because of the changes the 1960s and 1970s had brought to Dutch

society and culture, the strongly conservative Luns decided not to

return to his home country but settled in Brussels to spend his

remaining years in retirement. Joseph Luns died on July 17, 2002, aged 90.