<Back to Index>

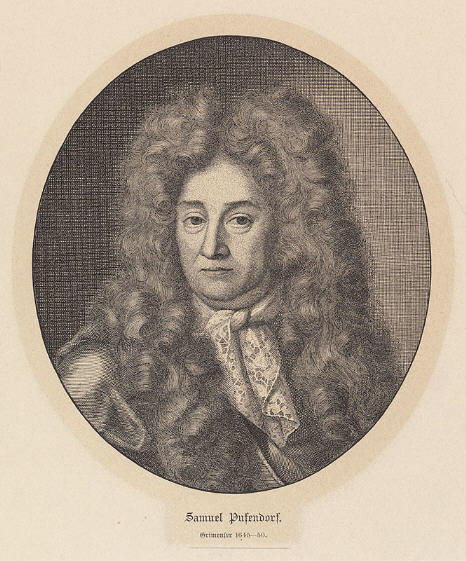

- Jurist Samuel von Pufendorf, 1632

- Writer Su Shi, 1037

- French Ambassador to the United States Edmond Charles Genêt, 1763

PAGE SPONSOR

Baron Samuel von Pufendorf (January 8, 1632 – October 13, 1694) was a German jurist, political philosopher, economist, statesman, and historian. His name was just Samuel Pufendorf until he was ennobled in 1684; he was made a Freiherr (baron) a few months before his death in 1694. Among his achievements are his commentaries and revisions of the natural law theories of Thomas Hobbes and Hugo Grotius.

He was born at Dorfchemnitz in the Electorate of Saxony. His father Elias Pufendorf from Glauchau was a Lutheran pastor, and Samuel Pufendorf himself was destined for the ministry.

Educated at the ducal school (Fürstenschule) at Grimma, he was sent to study theology at the University of Leipzig. The narrow and dogmatic teaching was repugnant to Pufendorf, and he soon abandoned it for the study of public law.

Leaving Leipzig altogether, Pufendorf relocated to the University of Jena, where he formed an intimate friendship with Erhard Weigel, the mathematician, whose influence helped to develop his remarkable independence of character. Under the influence of Weigel, he started to read Hugo Grotius, Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes.

Pufendorf left Jena in 1658 as Magister and became a tutor in the family of Petrus Julius Coyet, one of the resident ministers of King Charles X of Sweden, at Copenhagen with the help of his brother Esaias, a diplomat in the Swedish service.

At this time, Charles Gustavus was endeavouring to impose an unwanted alliance on Denmark, and in the middle of the negotiations he opened hostilities. The anger of the Danes was turned against the envoys of the Swedish sovereign; Coyet succeeded in escaping, but the second minister, Sten Bielke, and the rest of the staff were arrested and thrown into prison. Pufendorf shared this misfortune, and was held in captivity for eight months. He occupied himself in meditating upon what he had read in the works of Hugo Grotius and Thomas Hobbes, and mentally constructed a system of universal law. At the end of his captivity, he accompanied his pupils, the sons of Coyet, to the University of Leiden.

At Leiden, he was permitted to publish, in 1661, the fruits of his reflections under the title of Elementa jurisprudentiae universalis libri duo. The work was dedicated to Charles Louis, elector palatine, who created for Pufendorf a new chair at the University of Heidelberg, that of the law of nature and nations. This professorship was first of its kind in the world. Pufendorf married Katharina Elisabeth von Palthen, the widow of a colleague in 1665.

In 1667 he wrote, with the assent of the elector palatine, a tract, De statu imperii germanici liber unus. Published under the cover of a pseudonym at Geneva in 1667, it was supposed to be addressed by a gentleman of Verona, Severinus de Monzambano, to his brother Laelius. The pamphlet caused a sensation. Its author directly challenged the organization of the Holy Roman Empire, denounced in the strongest terms the faults of the house of Austria, and attacked with vigour the politics of the ecclesiastical princes. Before Pufendorf, Philipp Bogislaw von Chemnitz, publicist and soldier, had written, under the pseudonym of "Hippolytus a Lapide," De ratione status in imperio nostro romano - germanico. Inimical, like Pufendorf, to the Austrian House of Habsburg, Chemnitz had gone so far as to make an appeal to France and Sweden. Pufendorf, on the contrary, rejected all idea of foreign intervention, and advocated that of national initiative.

When Pufendorf went on to criticise a new tax on official documents, he did not get the chair of law and had to leave Heidelberg in 1668. Chances for advancement were few in a Germany that still suffered from the ravages of the Thirty Years' War (1618 - 1648), so Pufendorf went to Sweden where that year he was called to the University of Lund. His sojourn there was fruitful.

In 1672 appeared the De jure naturae et gentium libri octo, and in 1675 a résumé of it under the title of De officio hominis et civis ("On the Duty of Man and Citizen"), which, among other topics, gave his analysis of just war theory. In the De jure naturae et gentium Pufendorf took up in great measure the theories of Grotius and sought to complete them by means of the doctrines of Hobbes and of his own ideas. His first important point was that natural law does not extend beyond the limits of this life and that it confines itself to regulating external acts. He disputed Hobbes's conception of the state of nature and concluded that the state of nature is not one of war but of peace. But this peace is feeble and insecure, and if something else does not come to its aid it can do very little for the preservation of mankind.

As regards public law Pufendorf, while recognizing in the state (civitas) a moral person (persona moralis), teaches that the will of the state is but the sum of the individual wills that constitute it, and that this association explains the state. In this a priori conception, in which he scarcely gives proof of historical insight, he shows himself as one of the precursors of Rousseau and of the Contrat social. Pufendorf powerfully defends the idea that international law is not restricted to Christendom, but constitutes a common bond between all nations because all nations form part of humanity.

In 1677 Pufendorf was called to Stockholm as Historiographer Royal. To this new period belong Einleitung zur Historie der vornehmsten Reiche und Staaten, also the Commentarium de rebus suecicis libri XXVI., ab expeditione Gustavi Adolphi regis in Germaniam ad abdicationem usque Christinae and De rebus a Carolo Gustavo gestis.

In his historical works, Pufendorf wrote in a very dry style, but he

professed a great respect for truth and generally drew from archival

sources. In his De habitu religionis christianae ad vitam civilem he

traces the limits between ecclesiastical and civil power. This work

propounded for the first time the so-called "collegial" theory of

church government (Kollegialsystem), which, developed later by the learned Lutheran theologian Christoph Mathkus Pfaff, formed the basis of the relations of church and state in Germany and more especially in Prussia. This theory makes a fundamental distinction between the supreme jurisdiction in ecclesiastical matters (Kirchenhoheit or jus circa sacra),

which it conceives as inherent in the power of the state in respect of

every religious communion, and the ecclesiastical power (Kirchengewalt or jus in sacra)

inherent in the church, but in some cases vested in the state by tacit

or expressed consent of the ecclesiastical body. The theory was of

importance because, by distinguishing church from state while

preserving the essential supremacy of the latter, it prepared the way

for the principle of toleration. It was put into practice to a certain

extent in Prussia in

the 18th century; but it was not till the political changes of the 19th

century led to a great mixture of confessions under the various state

governments that it found universal acceptance in Germany. The theory,

of course, has found no acceptance in the Roman Catholic Church, but it

nonetheless made it possible for the Protestant governments to make a working compromise with Rome in respect of the Roman Catholic Church established in their states. In 1688 Pufendorf was called into the service of Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg. He accepted the call, but he had no sooner arrived than the elector died. His son Frederick III fulfilled

the promises of his father; and Pufendorf, historiographer and privy

councillor, was instructed to write a history of the Elector Frederick

William (De rebus gestis Frederici Wilhelmi Magni). The King of

Sweden continued to testify his goodwill towards Pufendorf, and in 1694

created him a baron. In the same year while still in Sweden, Pufendorf

suffered a stroke, and shortly thereafter died at Berlin.

He was buried in the church of St Nicholas, where an inscription to his

memory is still to be seen. He was succeeded as historiographer in

Berlin by Charles Ancillon. Pufendorf's

influence was considerable, and he has left a profound impression on

thought, and not on that of Germany alone. Locke, Rousseau, and Diderot

all recommended his inclusion in law curricula, and Pufendorf greatly

influenced Blackstone and Montesquieu. By way of these thinkers,

Pufendorf was introduced to and utilized by American Founders such as

Hamilton, Madison, and Jefferson as they formulated the political

thought of the new Republic. Pufendorf is seen as an

important precursor of Enlightenment in

Germany. He was involved in constant quarrels with clerical circles and

frequently had to defend himself against accusations of heresy. But

the value of his work has been historically underestimated. Much of the

responsibility for this may be attributed to Pufendorf's feuds with Leibniz, since they were often intellectual adversaries; indeed, Leibniz once dismissed Pufendorf as "vir parum jurisconsultus et minime philosophus" (roughly: "He is not much of a lawyer, and least of all a philosopher"). It was on the subject of the pamphlet of Severinus de Monzambano that

their quarrel began. The conservative and timid Leibniz was beaten on

the battlefield of politics and public law, and the aggressive spirit

of Pufendorf further aggravated the dispute, and so widened the

division. From that time the two writers could never discuss a common

subject without attacking each other.