<Back to Index>

- Jurist Samuel von Pufendorf, 1632

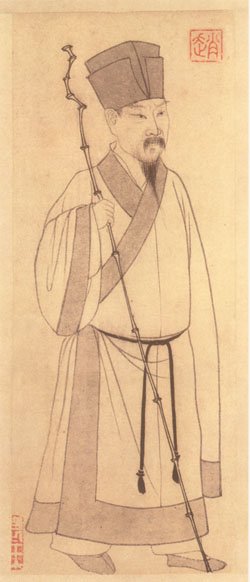

- Writer Su Shi, 1037

- French Ambassador to the United States Edmond Charles Genêt, 1763

PAGE SPONSOR

Su Shi (traditional Chinese: 蘇軾) (January 8, 1037 – August 24, 1101), was a writer, poet, artist, calligrapher, pharmacologist, and statesman of the Song Dynasty, and one of the major poets of the Song era. His courtesy name was Zizhan (子瞻) and his pseudonym was Dongpo Jushi (東坡居士), and he is often referred to as Su Dongpo (蘇東坡). Besides his renowned poetry, his other extant writings are of great value in the understanding of 11th century Chinese travel literature as well as details of the 11th century Chinese iron industry.

Su Shi was born in Meishan, near Mount Emei in what is now Sichuan province. His brother Su Zhe (蘇轍) and his father Su Xun (蘇洵) were both famous literati. Su's early education was conducted under a Taoist priest at a local village school. Later in his childhood, he studied under his mother, herself a highly educated woman. Su married at age 17. In 1057, when Su was 19, he and his brother passed the (highest level) civil service examinations to attain the degree of jinshi, a prerequisite for high government office. His accomplishments at such a young age attracted the attention of Ouyang Xiu, who became Su's patron thereafter. Ouyang had already been known as an admirer of Su Xun, sanctioning his literary style at court and stating that no other pleased him more. When the 1057 jinshi examinations were given, Ouyang Xiu required — without prior notice — that candidates were to write in the ancient prose style when answering questions on the Confucian classics. The Su brothers gained high honors for what were deemed impeccable answers and achieved celebrity status.

Beginning in 1060 and throughout the following twenty years, Su held a variety of government positions throughout China; most notably in Hangzhou, where he was responsible for constructing a pedestrian causeway across the West Lake that still bears his name: suti (蘇堤, Su causeway). He had served as a magistrate in Mizhou, which is located in modern day Zhucheng County of Shandong province. Later, when he was governor of Xuzhou, he once wrote a memorial to the throne in 1078 complaining about the troubling economic conditions and potential for armed rebellion in Liguo Industrial Prefecture, where a large part of the Chinese iron industry was located.

Su Shi was often at odds with a political faction headed by Wang Anshi. Su Shi once wrote a poem criticizing Wang Anshi's reforms, especially the government monopoly imposed on the salt industry. The dominance of the reformist faction at court allowed the New Policy Group greater ability to have Su Shi exiled for political crimes. The claim was that Su was criticizing the emperor, when in fact Su Shi's poetry was aimed at criticizing Wang's reforms. It should be said that Wang Anshi played no part in this actions against Su, for he had retired from public life in 1076 and established a cordial relationship with Su Shi. Su Shi's first remote trip of exile (1080 – 1086) was to Huangzhou, Hubei. This post carried a nominal title, but no stipend, leaving Su in poverty. During this period, he began Buddhist meditation. With help from a friend, Su built a small residence on a parcel of land in 1081. Su Shi lived at a farm called Dongpo ('Eastern Slope'), from which he took his literary pseudonym. While banished to Hubei province, he grew fond of the area he lived in; many of the poems considered his best were written in this period. His most famous piece of calligraphy, Han Shi Tie, was also written there. In 1086, Su and all other banished statesmen were recalled to the capital due to the ascension of a new government. However, Su was banished a second time (1094 – 1100) to Huizhou (now in Guangdong province) and Hainan island. In 1098 the Dongpo Academy in Hainan was built on the site of the residence that he lived in whilst in exile.

Although political bickering and opposition usually split ministers of court into rivaling groups, there were moments of non - partisanship and cooperation from both sides. For example, although the prominent scientist and statesman Shen Kuo (1031 – 1095) was one of Wang Anshi's most trusted associates and political allies, Shen nonetheless befriended Su Shi and even collaborated with him in compiling the pharmaceutical treatise of the Liang Fang (良方; Good medicinal formulas). It should be noted, however, that Su Shi was aware that it was Shen Kuo who, as regional inspector of Zhejiang, presented Su Shi's poetry to the court sometime between 1073 to 1075 with concern that it expressed abusive and hateful sentiments against the Song court. It was these poetry pieces that Li Ding and Shu Dan later utilized in order to instigate a law case against Su Shi, although until that point Su Shi did not think much of Shen Kuo's actions in bringing the poetry to light.

After a long period of political exile, Su received a pardon in 1100 and was posted to Chengdu. However, he died in Changzhou, Jiangsu province after his period of exile and while he was en route to his new assignment in the year 1101. Su Shi was 64 years old. After his death he gained even greater popularity, as people sought to collect his calligraphy, paintings depicting him, stone inscriptions marking his visit to numerous places, and built shrines in his honor. He was also depicted in artwork made posthumously, such as in Li Song's (1190 – 1225) painting of Su traveling in a boat, known as Su Dongpo at Red Cliff, after Su Song's poem written about a 3rd century Chinese battle.

Su Shi had two wives and a concubine. His first wife was Wang Fu (王弗, 1039 - 1065), an astute, quiet lady from Sichuan who married him at the age of sixteen, when Su was nineteen. Wang Fu died in 1065, on the second day of the fifth Chinese lunar month (Gregorian calendar June 14), after bearing him Su Mai (蘇邁). Heartbroken, Su wrote a memorial for Wang (《亡妻王氏墓志铭》), stating Fu was not just a virtuous wife but advised him frequently on the integrity of his acquaintances when he was an official.

Ten years after Su Shi's first wife died, Su composed a (ci) poem after dreaming of the deceased Fu in the night at Mizhou (present day Zhucheng). The poem, To the tune of 'Of Jinling' (江城子), remains one of the most famous poems Su wrote:

《江城子•乙卯正月二十日夜記夢》

蘇軾

十年生死兩茫茫,不思量, 自難忘。千里孤墳,無處話淒涼。縱使相逢應不識,塵滿面,鬢如霜。

夜來幽夢忽還鄉,小軒窗,正梳妝。相顧無言,惟有淚千行。料得年年腸斷處,明月夜,短松岡。

In 1068, two years after Wang Fu's death, Su married Wang Runzhi (王 闰之, 1048 - 93), Fu's paternal younger cousin and his junior by eleven years. Wang Runzhi spent the next 15 years accompanying Su through his ups and downs in officialdom and political exile. Su praised Runzhi for being an understanding wife who treated his three sons equally (his eldest, Su Mai, was borne by Fu). Once, Su was angry with his young son for not understanding his unhappiness during his political exile, and Wang chided Su himself for his silliness, prompting Su to write the domestic poem My Young Son 《小兒》:

《小兒》

小兒不識愁,起坐牽我衣。我欲嗔小兒,老妻勸兒癡。兒癡君更甚,不樂復何為?還坐愧此言,洗盞當我前。大勝劉伶婦,區區為酒錢。

My Young Son

- My young son knows no grief:

- he tagged at my garment upon sitting upright.

- I was just about to lose my temper

- when my old wife chided the boy for being silly.

- "But my husband's sillier than the son," she said.

- "why not just be happy?"

- I sat upright, embarrassed by her words;

- she placed a washed wine cup before me.

- She's far better than Liu Ling's wife

- who got mad with her husband for spending on wine!

Wang Runzhi died in 1093, aged forty - six, after bearing Su two sons, Su Dai (蘇迨) and Su Guo (蘇過). Overcame with grief, Su expressed his wish to be buried with her in her memorial. During his deceased second wife's birthday, Su wrote another ci poem, To the tune of 'Butterflies going after Flowers' (《蝶恋花》), for her:

《蝶恋花》

泛泛東風初破五。江柳微黃,萬萬千千縷。佳氣郁蔥來繡戶,當年江上生奇女。一盞壽觴誰與舉。三個明珠,膝上王文度。放盡窮鱗看圉圉,天公為下曼陀雨。

To the Tune of 'Butterflies going after Flowers'

- A wafting east breeze breaks on the Fifth's dawn.

- Willows by the Yangtze, yellow-wan,

- interweave in its tens of thousands.

- A festive air comes luxuriantly to these patterned gateways.

- Once a wondrous lady was born along this stream:

- with whom shall I raise this wine-cup, on her birthday,

- though she's now deceased?

- Three offspring pearls, all placed lovingly on her lap,

- like Wang Wendu.

- I release countless carps,

- watch them squirm lazy,

- uncomfortably, away

- as the Lord of Heavens lets down Datura rain.

Su's concubine Wang Zhaoyun (王朝雲, 1062 - 1095) was his handmaiden who was a former Qiantang singing artiste. Su redeemed Wang when she was twelve years old and she later became his concubine, teaching herself to read though she was formerly illiterate. Zhaoyun was probably the most famous of Su's companions. Su's friend Qin Guan wrote a poem, A Gift for Dongpo's concubine Zhaoyun 《贈東坡妾朝雲》, praising her beauty and lovely voice. Su dedicated a number of his poems to Zhaoyun, like To the Tune of 'Song of the South'《南歌子》, Verses for Zhaoyun 《朝雲詩》, To the Tune of 'The Beauty Who asks One to Stay' 《殢人娇·贈朝雲》, To the Tune of 'The Moon at Southern Stream' 《西江月》. Zhaoyun remained a faithful companion to Su after Runzhi's death, but died of illness on August 13, 1095 (绍圣三年七月五日) at Huizhou. Zhaoyun bore Su a son Su Dun (蘇遁) on November 15, 1083, who died in his infancy. After Zhaoyun's death, Su never married again.

Su Shi had three adult sons, the eldest son being Su Mai (蘇邁), who would also become a government official by 1084. Su Dai (蘇迨) and Su Guo (蘇過) are his other sons. When Su Shi died in 1101, his younger brother Su Zhe buried him alongside second wife Wang Runzhi according to his wishes.

Around 2,700 of Su Song's poems have survived, along with 800 written letters. Su Dongpo excelled in the shi, ci and fu forms of poetry, as well as prose, calligraphy and painting. Some of his notable poems include the First and Second Chibifu (赤壁賦 The Red Cliffs, written during his first exile), Nian Nu Jiao: Chibi Huai Gu (念奴嬌.赤壁懷古 Remembering Chibi, to the tune of Nian Nu Jiao) and Shui diao ge tou (水調歌頭 Remembering Su Che on the Mid - Autumn Festival, 中秋節). The two former poems were inspired by the 3rd century naval battle of the Three Kingdoms era, the Battle of Chibi in the year 208. The bulk of his poems are in the shi style, but his poetic fame rests largely on his 350 ci style poems. Su Shi also founded the haofang school, which cultivated an attitude of heroic abandon. In both his written works and his visual art, he combined spontaneity, objectivity and vivid descriptions of natural phenomena. Su Shi wrote essays as well, many of which are on politics and governance, including his Liuhoulun (留侯論). His popular politically charged poetry was often the reason of Wang Anshi's supporter's wrath towards him, including this poem criticizing Wang Anshi's stiff reforms of the salt monopoly that made salt increasingly hard to find:

essays', which belonged in part to the popular Song era literary category of 'travel record literature' (youji wenxue) that employed the use of narrative, diary, and prose styles of writing. Although other works in Chinese travel literature contained a wealth of cultural, geographical, topographical, and technical information, the central purpose of the daytrip essay was to use a setting and event in order to convey a philosophical or moral argument, which often employed persuasive writing. For example, Su Shi's daytrip essay known as Record of Stone Bell Mountain, where he judges and then personally discovers whether or not ancient texts on 'stone bells' were factually accurate:The Waterway Classic says: "At the mouth of a Pengli [Lake] there is a Stone Bell Mountain." Li Daoyuan (d. 527) held that "below it, near a deep pool, faint breezes drum up waves, and water and rocks striking one another toll like huge bells." Others have often doubted this claim. Today, if one takes a bell or a lithophone and places it into the water, even if there is great wind and waves, you cannot make it ring. How much the less, then, for [common] rocks? It was not until the time of Li Bo [9th century, not the famous Li Bo, or Li Bai] of the Tang that someone searched for a surviving trace of this phenomenon. Upon finding a pair of rocks on the bank of a pool, he knocked them together and listened. Their southern tone was mellow and muted; their northern timber was clear and shrill. When the clang ceased, its resonance mounted; the remnant notes then gradually came to rest. Li Bo then held that he had found the 'stone bells'. However, I am especially doubtful of this statement. The clanking sound made by rocks is the same everywhere. And yet, this place alone is named after a bell. Why, indeed, is that?

On Dingchou day of the sixth lunar month in the seventh year of the Prime Abundance period (July 14, 1084), I was traveling by boat from Qi'an (Huanggang, Hubei) to Linru (Linru, Henan). My oldest son [Su] Mai was just about to leave for Dexing in Rao to take up the post of Pacificator. Since I accompanied him as far as Hukou (modern Hukou, Jiangxi), I was able to observe the so-called stone bells. A monk from a [nearby] monastery dispatched an apprentice carrying an axe to select one or two among the scattered rocks and knock them [with an axe], upon which they made a 'gong - gong' - like sound. I laughed just as I had done before and still did not believe the legend.

That evening, the moon was bright. Alone with Mai I rode a little boat to the base of a steep precipice. The huge rocks on our flank stood 1000 feet high (304 m). They looked like fierce beasts and weird goblins, lurking in a ghastly manner and getting ready to attack us. When the roosting falcons on the mountain heard our voices they too flew off in fright, cawing and crying in the cloudy empyrean. Further, there was something [that sounded] like an old man coughing and laughing in a mountain ravine. Someone said: "That is a white stork." I was shaking with fear and about to turn back, when a loud noise rang out from the surface of the water that gonged and bonged like bells and drums unceasing in their clamor. The boatmen became greatly alarmed. I carefully investigated it, only to discover that everywhere below the mountain there are rocky caves and fissures, who knows how deep. Gentle waves were pouring into them, and their shaking and seething, and chopping and knocking were making this gonging and bonging. When our boat on its return reached a point between the two mountains and we were about to enter the mouth of the inlet, [I saw that] there was a huge rock in the middle of the channel which could seat a hundred people. It was hollow in the center with numerous apertures, which, as they swallowed and spat with the wind and water, made a bumping and thumping and clashing and bashing that echoed with the earlier gonging and bonging. It seemed as if music was being played here. Thereupon, I laughed and said to Mai: "Do you recognize it? The gonging and bonging is the Wuyi bell of King Jing of Zhou; the bumping and thumping and clashing and bashing are the song - bells of Wei Zhuangzi [a.k.a. Wei Jiang; 6th century BC military advisor]. The ancients [i.e. Li Daoyuan and Li Bo] have not cheated us!

Is it acceptable for someone who has not personally seen or heard something to have decided views on whether it exists or not? Li Daoyuan probably saw and heard the same things as I did, yet he decided not to describe them in detail. Gentlemen officials have always been unwilling to take a small boat and moor it beneath the steep precipice at night. Thus, none were able to find out [about the bells]. And, although the fishermen and boatmen knew about them, they were unable to describe them [in writing]. This is why it has not been transmitted through the generations. As it turns out, imbeciles sought the answer by taking axes and beating and striking rocks. Then they held that they had found out the truth of the matter. Because of this I have made a record of these events, for the most part to sigh over Li Daoyuan's superficiality, and to laugh at Li Bo's stupidity!

While acting as Governor of Xuzhou, Su Shi once wrote a memorial to the imperial court in 1078 AD about problems faced in the Liguo Industrial Prefecture, which was under his watch and administration. In an interesting and revealing passage about the Chinese iron industry during the latter half of the 11th century, Su Shi wrote about the enormous size of the workforce employed in the iron industry, competing provinces that had rival iron manufacturers seeking favor from the central government, as well as the danger or rising local strongmen who had the capability of raiding the industry and threatening the government with effectively armed rebellion. It also becomes clear in reading the text that prefectural government officials in Su's time often had to negotiate with the central government in order to meet the demands of local conditions:

After being transferred to the governorship of Xuzhou I have inspected the topography of [the region's] mountains and rivers, investigated what is esteemed by its customs, and studied it in written records. After all this I have realized that Xuzhou is a strategic point between North and South, on which the security of the circuits East of the capital depends... [The region is protected on three sides by rugged mountains. Four historical examples show the strategic importance of the prefecture, especially its administrative seat, the walled city of Pengcheng.] About 70 li northeast of the prefecture city is Liguo Industrial Prefecture. From ancient times it has been the gathering place of Iron Offices [tieguan] and merchants, and its people are prosperous. There are 36 smelters, each run by a wealthy and influential family with great myriads of cash in its coffers. They are a constant target for bandits, but the military guard is weak, and it is child's play [to rob them].

I have pondered this far into the night, filled with anxiety. I have had more than ten of the most powerful bandits put to death, [but still] when they enter the market in broad daylight the guards abandon their posts and flee. This region produces fine iron, and the people are all excellent smiths. If some of the smelting households' money is distributed to call up [the local] hoodlums, then a mob could quickly be gathered, and weapons for several thousand men could be supplied in no time. If such a mob were to follow the river and come south, it would arrive [in Pengcheng] in a matter of hours, and Xuzhou would be defenseless. Should the misfortune arise that the bandits had exceptional ability, ...and they fulfilled their ambition by taking Xuzhou, then the fate of the region East of the Capital would be in doubt.

Recently the Fiscal Commission of Hebei proposed that iron from Liguo Industrial Prefecture should not be permitted to enter Hebei, and the Court approved... The Empire is one family, and the two smelting [regions] of the northeast both benefit the State; is it not narrow to take from the one to give to the other? Since the time that iron stopped going north the smelting households have been in danger of bankruptcy, and many have come to me to complain. I propose therefore to call on the smelting households to be the defense of Liguo Industrial Prefecture. There are 36 smelters, and each has several hundred persons who gather ore and chop [wood for] charcoal. They are for the most part poverty stricken runaways, strong and fierce. I propose to require the smelting households to select and appoint ten men of ability and discipline from each smelter and register their names with the officials. These will be trained in the use of knives and spears. Each month the two offices will assemble them at the administrative headquarters of Liguo Industrial Prefecture for inspection and drill. They will be excused from corvée duty, but any offenses will be treated under the law pertaining to 'malfeasance in official service'.

The smelting households have long been threatened by bandits. All the people know this, and they will be delighted to have each smelter send ten men for self - defense. If the officials also remove the recent prohibition, and again allow the iron to go north, then the smelting households will be satisfied and obedient. Treacherous elements will be terrified and will not dare to make plots.

During the ancient Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD) of China, the sluice gate and canal lock of the flash lock had been known. By the 10th century the latter design was improved upon in China with the invention of the canal pound lock, allowing different adjusted levels of water along separated and gated segments of a canal. This innovation allowed for larger transport barges to pass safely without danger of wrecking upon the embankments, and was an innovation praised by those such as Shen Kuo (1031 – 1095). Shen also wrote in his Dream Pool Essays of the year 1088 that if properly used, sluice gates positioned along irrigation canals were most effective in depositing silt for fertilization. Writing earlier in his Dongpo Zhilin of 1060, Su Shi came to a different conclusion, writing that the Chinese of a few centuries past had perfected this method and noted that it was ineffective in use by his own time. He wrote:

Several years ago the government built sluice gates for the silt fertilization method, though many people disagreed with the plan. In spite of all opposition it was carried through, yet it had little success. When the torrents on Fan Shan were abundant, the gates were kept closed, and this caused damage (by flooding) of fields, tombs, and houses. When the torrents subsided in the late autumn the sluices were opened, and thus the fields were irrigated with silt - bearing water, but the deposit was not as thick as what the peasants call 'steamed cake silt' (so they were not satisfied). Finally the government got tired of it and stopped. In this connection I remember reading the Jiayipan of Bai Juyi (the poet) in which he says that he once had a position as Traffic Commissioner. As the Bian River was getting so shallow that it hindered the passage of boats he suggested that the sluice gates along the river and canal should be closed, but the Military Governor pointed out that the river was bordered on both sides by fields which supplied army grain, and if these were denied irrigation (water and silt) because of the closing of the sluice gates, it would lead to shortages in army grain supplies. From this I learnt that in the Tang period there were government fields and sluice gates on both sides of the river, and that irrigation was carried on (continuously) even when the water was high. If this could be done (successfully) in old times, why can it not be done now? I should like to enquire further about the matter from experts.

Although Su Shi made no note of it in his writing, the root of this problem was merely the needs of agriculture and transportation conflicting with one another.

It is said that once during his free time, Su Dongpo decided to make

stewed pork out of boredom. Then an old friend visited him in the middle of the cooking and challenged him to a game of Chinese chess.

Su had totally forgotten of the stew during the game until a very

fragrant smell came out from his kitchen and he was reminded of it. Thus Dongpo's Pork (東坡肉), a famous dish in Chinese cuisine, was created by accident.