<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Henry Frederick Baker, 1866

- Composer and Governor of Taganrog Achilles Nikolayevich Alferaki, 1846

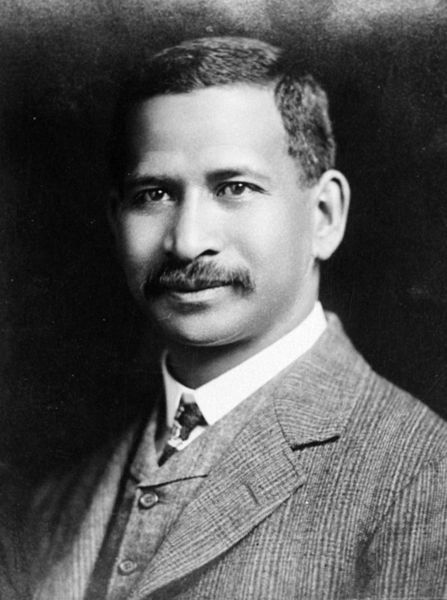

- Minister of Māori Affairs Apirana Turupa Ngata, 1874

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Apirana Turupa Ngata (3 July 1874 – 14 July 1950) was a prominent New Zealand politician and lawyer. He has often been described as the foremost Māori politician to have ever served in Parliament, and is also known for his work in promoting and protecting Māori culture and language.

One of 15 children, Ngata was born in Te Araroa (then called Kawakawa), a small coastal town about 175 kilometres north of Gisborne, New Zealand. His iwi was Ngāti Porou, and his father was considered an expert in traditional lore. Ngata was greatly influenced both by his father and by his great - uncle Ropata Wahawaha (who had led Ngāti Porou forces in the land wars). Ngata was raised in a Māori environment, speaking the Māori language, but his father also ensured that Ngata learned about the Pākehā world, believing that this understanding would be of benefit to Ngāti Porou.

Ngata attended primary school in Waiomatatini before moving on to Te Aute College, where he received a Pākehā style education. Ngata performed well, and his academic results were enough to win him a scholarship to Canterbury University College (now the University of Canterbury), where he studied political science and law. He gained a BA in politics in 1893, the first Māori to complete a degree at a New Zealand university, then gained an LL.B. at the University of Auckland in 1896 (the first New Zealander, Maori or Pakeha, to gain a double degree).

In 1895, a year before finishing his law degree, Ngata married 16 year old Arihia Kane Tamati who was also of the Ngāti Porou iwi. Ngata had previously been engaged to Arihia's elder sister, Te Rina, but she died. Apirana and Arihia had eight children, four girls and four boys.

Shortly after Ngata's legal qualifications were recognised, he and his wife returned to Waiomatatini where they built a house. Ngata quickly became prominent in the community, making a number of efforts to improve the social and economic conditions of Māori across the country. He also wrote extensively on the place of Māori culture in the modern age. At the same time, he gradually acquired a leadership role within Ngāti Porou, particularly in the area of land management and finance.

Ngata's first involvement with national politics came through his friendship with James Carroll, who was Minister of Native Affairs in the Liberal Party government.

Ngata assisted Carroll in the preparation of two pieces of legislation,

both of which were intended to increase the legal rights enjoyed by

Māori. In the 1905 election, Ngata himself stood as the Liberal candidate for the Eastern Maori electorate, challenging the incumbent Wi Pere. He was elected to Parliament. Ngata

quickly distinguished himself in Parliament as a skilled orator. He

worked closely with his friend Carroll, and also worked closely with Robert Stout.

Ngata and Stout, members of the Native Land Commission, were often

critical of the government's policies towards Māori, particularly those

designed at encouraging the sale of Māori land. In 1909, Ngata assisted John Salmond in the drafting of the Native Land Act. In late 1909, Ngata was appointed to Cabinet,

holding a minor ministerial responsibility for Māori land councils. He

retained this position until 1912, when the Liberal government was

defeated. Ngata followed the Liberals into Opposition. In the First World War, Ngata was highly active in gathering Māori recruits for military service, working closely with Reform Party MP Maui Pomare.

Ngata's own Ngāti Porou were particularly well represented among the

volunteers. The large Māori commitment to the war, much of which can be

attributed to Ngata and Pomare, created a certain amount of goodwill

from Pākehā towards Māori, and assisted Ngata's later attempts to

resolve land grievances. Although

in Opposition, Ngata enjoyed relatively good relations with his

counterparts across the House in the Reform Party. He had a

particularly good relationship with Gordon Coates, who became Prime Minister in

1925. The establishment of several government bodies, such as the Māori

Purposes Fund Control Board and the Board of Māori Ethnological Research, owed much to Ngata's involvement. During

this time, Ngata was also active in a huge variety of other endeavours.

The most notable, perhaps, was his involvement in academic and literary

circles - in this period, he published a number of works on significant

Māori culture, with Nga moteatea,

a collection of Māori songs, being one of his better known works. Ngata

was also heavily involved in the protection and advancement of Māori

culture among Māori themselves, giving particular attention to

promoting the haka, poi dancing,

and traditional carving. One aspect of his advocacy of Māori culture

was the construction of many new traditional meeting houses throughout

the country. Yet another of Ngata's interests was the promotion of

Māori sport, which he fostered by encouraging intertribal competitions

and tournaments. Finally, Ngata also promoted Māori issues within the Anglican Church, encouraging the creation of a Māori bishopric.

Throughout all this, Ngata also remained deeply involved in the affairs

of his Ngāti Porou iwi, particularly as regards land development. Ngata was knighted in 1927, only the third Māori (after Carroll and Pomare) to receive this honour. In the 1928 elections,

the United Party (a rebranding of the old Liberal Party, to which Ngata

belonged) won an unexpected victory. Ngata was returned to Cabinet,

becoming Minister of Native Affairs. He was ranked third within Cabinet, and occasionally served as acting Deputy Prime Minister.

Ngata remained extremely diligent in his work, and was noted for his

tirelessness. Much of his ministerial work related to land reforms, and

the encouragement of Māori land development. Ngata continued to believe

in the need to rejuvenate Māori society, and worked strongly towards

this goal. In 1929, both Ngata's wife and eldest son died of illness. In

1932 Ngata and his Department of Native Affairs came under increasing

criticism from other politicians. Many believed that Ngata was pressing

ahead too fast, and the large amount of activity that Ngata ordered had

caused organizational difficulties within the department. An inquiry

into Ngata's department was held, and it was discovered that one of

Ngata's subordinates had falsified accounts. Ngata himself was

criticised for disregarding official regulations which he had often

felt were inhibiting progress. It was also alleged that Ngata had shown

favouritism to Ngāti Porou, although no real evidence of this was ever

presented. Ngata, while denying any personal wrongdoing, accepted

responsibility for the actions of his department and resigned from his

ministerial position. Many

Māori were angry at Ngata's departure from Cabinet, believing that he

was the victim of a Pākehā attempt to undermine his land reforms. Although Ngata had resigned from Cabinet, he still remained in Parliament. In the 1935 elections, the Labour Party was

triumphant - Ngata went into Opposition, although the new Labour

government retained many of his land reform programs. Ngata remained in

Parliament until the 1943 elections, when he was finally defeated by a Labour - Ratana candidate, Tiaki Omana. He stood again for his seat in the 1946 elections, but was unsuccessful. Despite leaving Parliament, Ngata remained involved in politics. He gave advice on Māori affairs to both Peter Fraser (a Labour Prime Minister) and Ernest Corbett (a National Minister of Māori Affairs), and arranged celebrations of the Treaty of Waitangi's centenary in 1940. In the Second World War, he once again helped gather Māori recruits. In 1950, he was appointed to Parliament's upper house, the Legislative Council, but was too ill by this time to take his seat. Ngata

died in Waiomatatini on 14 July 1950. He is remembered for his great

contributions to Māori culture and language. His image appears on New

Zealand's $50 note. On

October 19, 2009, Apirana Ngata's last surviving daughter, Mate Huatahi

Kaiwai (born Ngata), died at her residence at Ruatoria, East Cape, New

Zealand, aged 94. She was interred next to her late husband

Kaura - Ki - Te - Pakanga Kaiwai and her son Tanara Kaiwai at Pukearoha

Urupa. Apirana Ngata has one surviving child, his youngest son, Sir

Henare Ngata (born 1918).