<Back to Index>

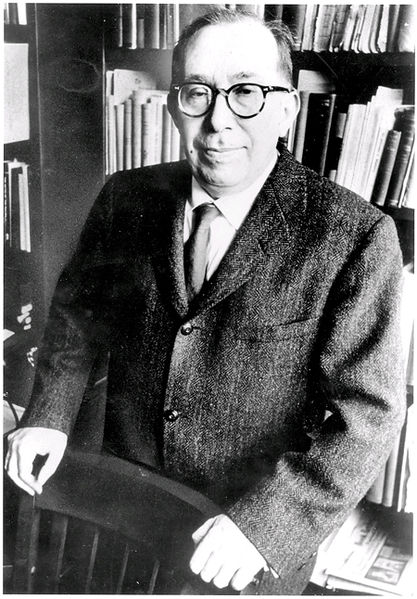

- Political Philosopher Leo Strauss, 1899

- Writer Upton Beall Sinclair Jr., 1878

- Explorer and Colonial Administrator Maurice Benyovszky, 1746

PAGE SPONSOR

Leo Strauss (September 20, 1899 – October 18, 1973) was a political philosopher who specialized in classical political philosophy. He was born in Germany to Jewish parents and later emigrated to the United States. He spent most of his career as a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, where he taught several generations of students and published fifteen books.

Originally trained in the Neo - Kantian tradition with Ernst Cassirer and later acquainted with phenomenologists such as Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, Strauss later focused his research on Greek texts of Plato and Aristotle, and encouraged application of their ideas on contemporary political theory.

Leo Strauss was born in the

small town of Kirchhain in Hesse - Nassau, a province of the Kingdom of Prussia (part

of the German Empire), on September 20,

1899, to Hugo Strauss and Jennie Strauss,

née David. According to Allan Bloom's 1974 obituary in Political

Theory, Strauss "was raised as an Orthodox Jew,"

but the family does not appear to have completely

embraced Orthodox practice. In "A

Giving of Accounts", published in The

College 22

(1) and later reprinted in Jewish

Philosophy and

the Crisis of Modernity,

Strauss noted he came from a "conservative, even orthodox Jewish

home," but one which knew little about Judaism

except strict adherence to ceremonial laws. His

father and uncle operated a farm supply and

livestock business that they inherited from their

father, Meyer (1835 – 1919), a leading member of

the local Jewish community.

After attending the Kirchhain Volksschule and the Protestant Rektoratsschule, Leo Strauss was enrolled at the Gymnasium Philippinum (affiliated with the University of Marburg) in nearby Marburg (from which Johannes Althusius and Carl J. Friedrich also graduated) in 1912, graduating in 1917. He boarded with the Marburg Cantor Strauss (no relation); the Cantor's residence served as a meeting place for followers of the neo - Kantian philosopher Hermann Cohen. Strauss served in the German army during World War I from July 5, 1917 to December 1918.

Strauss subsequently enrolled in the University of Hamburg, where he received his doctorate in 1921; his thesis, "On the Problem of Knowledge in the Philosophical Doctrine of F.H. Jacobi", was supervised by Ernst Cassirer. He also attended courses at the Universities of Freiburg and Marburg, including some taught by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Strauss joined a Jewish fraternity and worked for the German Zionist movement, which introduced him to various German Jewish intellectuals, such as Norbert Elias, Leo Löwenthal, Hannah Arendt and Walter Benjamin. Strauss' closest friend was Jacob Klein but he also was intellectually engaged with Karl Löwith, Gerhard Krüger, Julius Guttman, Hans - Georg Gadamer, Franz Rosenzweig (to whom Strauss dedicated his first book), Gershom Scholem, Alexander Altmann, and the Arabist Paul Kraus, who married Strauss' sister Bettina (Strauss and his wife later adopted their child when both parents died in the Middle East). With several of these friends, Strauss carried on vigorous epistolary exchanges later in life, many of which are published in the Gesammelte Schriften (Collected Writings), some in translation from the German. Strauss had also been engaged in a discourse with Carl Schmitt. However, when Strauss left Germany, he broke off this discourse when Schmitt failed to answer his letters.

In 1931 Strauss sought his post - doctoral (Habilitation) with the theologian Paul Tillich, but was turned down. After receiving a Rockefeller Fellowship in 1932, Strauss left his position at the Academy of Jewish Research in Berlin for Paris. He returned to Germany only once, for a few short days 20 years later. In Paris he married Marie (Miriam) Bernsohn, a widow with a young child whom he had known previously in Germany. He adopted his wife's son, Thomas, and later his sister's child; he and Miriam had no biological children of their own. At his death he was survived by Thomas, his sister's daughter Jenny Strauss Clay, and three grandchildren. Strauss became a lifelong friend of Alexandre Kojève and was on friendly terms with Raymond Aron, Alexandre Koyré, and Étienne Gilson. Because of the Nazis' rise to power, he chose not to return to his native country. Strauss found shelter, after some vicissitudes, in England, where in 1935 he gained temporary employment at University of Cambridge, with the help of his in - law, David Daube, who was affiliated with Gonville and Caius College. While in England, he became a close friend of R.H. Tawney, and was on less friendly terms with Isaiah Berlin.

Unable to find permanent

employment in England, Strauss moved in 1937 to

the United States, under the patronage of Harold Laski, who bestowed upon

Strauss a brief lectureship. After a short stint

as Research Fellow in

the Department of History at Columbia University, Strauss

secured a position at The New School,

where, between 1938 and 1948, he eked out a hand -

to - mouth living in the political science

faculty. In 1939, he served for a short term as a

visiting professor at Hamilton College. He became a U.S.

citizen in 1944, and in 1949 he became a professor

of political science at

the University of Chicago,

where he received, for the first time in his life,

a good wage. In 1954 he met Löwith and Gadamer in Heidelberg and

delivered a public speech on Socrates. Strauss held the Robert

Maynard Hutchins Distinguished Service

Professorship in Chicago until 1969. He had

received a call for a temporary lectureship in Hamburg in 1965

(which he declined for health reasons) and

received and accepted an honorary doctorate from Hamburg

University and

the Bundesverdienstkreuz

(German Order of Merit) via the German

representative in Chicago. In 1969 Strauss moved

to Claremont McKenna

College (formerly

Claremont Men's College) in California for a year,

and then to St. John's College, Annapolis, in 1970,

where he was the Scott Buchanan Distinguished

Scholar in Residence until his death from

pneumonia in 1973.

For Strauss, politics and philosophy were necessarily intertwined. He regarded the trial and death of Socrates as the moment when political philosophy came into existence. Strauss considered one of the most important moments in the history of philosophy Socrates' argument that philosophers could not study nature without considering their own human nature, which, in the words of Aristotle, is that of "a political animal."

Strauss distinguished "scholars" from "great thinkers", identifying himself as a scholar. He wrote that most self - described philosophers are in actuality scholars, cautious and methodical. Great thinkers, in contrast, boldly and creatively address big problems. Scholars deal with these problems only indirectly by reasoning about the great thinkers' differences.

In Natural Right and History Strauss begins with a critique of Max Weber's epistemology, briefly engages the relativism of Martin Heidegger (who goes unnamed), and continues with a discussion of the evolution of natural rights via an analysis of the thought of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. He concludes by critiquing Jean - Jacques Rousseau and Edmund Burke. At the heart of the book are excerpts from Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero. Much of his philosophy is a reaction to the works of Heidegger. Indeed, Strauss wrote that Heidegger's thinking must be understood and confronted before any complete formulation of modern political theory is possible.

Strauss wrote that Friedrich Nietzsche was the

first philosopher to properly understand relativism, an idea grounded in a

general acceptance of Hegelian historicism. Heidegger, in Strauss'

view, sanitized and politicized Nietzsche, whereas

Nietzsche believed "our own principles, including the

belief in progress, will become as relative as all

earlier principles had shown themselves to be" and

"the only way out seems to be... that one voluntarily

choose life - giving delusion instead of deadly truth,

that one fabricate a myth". Heidegger

believed that the tragic nihilism of

Nietzsche was a "myth" guided by a defective Western

conception of Being that

Heidegger traced to Plato. In his published

correspondence with Alexandre Kojève, Strauss wrote

that Hegel was

correct when he postulated that an end of history

implies an end to philosophy as understood by

classical political philosophy.

In 1952 Strauss published Persecution and the Art of Writing, commonly understood to advance the argument that some philosophers write esoterically in order to avoid persecution by political or religious authorities. A few readers of Strauss suggest esoteric writing may also seek to protect politics from political philosophy – the reasoning of which might negatively affect opinions undergirding the political order. Stemming from his study of Maimonides and Al Farabi, and then extended to his reading of Plato (he mentions particularly the discussion of writing in the Phaedrus), Strauss proposed that an esoteric text was the proper type for philosophic learning. Rather than simply outlining the philosopher's thoughts, the esoteric text forces readers to do their own thinking and learning. As Socrates says in the Phaedrus, writing does not respond when questioned, but invites a dialogue with the reader, thereby reducing the problems of the written word. One political danger Strauss pointed to was the acceptance of dangerous ideas too quickly by students. This was perhaps also relevant in the trial of Socrates, where his relationship with Alcibiades was used against him.

Ultimately, Strauss believed that

philosophers offered both an "exoteric" or salutary

teaching and an "esoteric" or true teaching, which was

concealed from the general reader. For maintaining

this distinction, Strauss is often accused of having

written esoterically himself. Moreover he also

emphasized that writers often left contradictions and

other excuses to encourage the more careful

examination of the writing. Leo Strauss's favorite

novelist was Jane Austen.

According to Strauss, modern social science is flawed because it assumes the fact - value distinction, a concept which Strauss finds dubious, tracing its roots in Enlightenment philosophy to Max Weber, a thinker whom Strauss described as a "serious and noble mind.” Weber wanted to separate values from science but, according to Strauss, was really a derivative thinker, deeply influenced by Nietzsche’s relativism. Strauss treated politics as something that could not be studied from afar. A political scientist examining politics with a value - free scientific eye, for Strauss, was self - deluded. Positivism, the heir to both Auguste Comte and Max Weber in the quest to make purportedly value - free judgments, failed to justify its own existence, which would require a value judgment.

While modern liberalism had

stressed the pursuit of individual liberty as its

highest goal, Strauss felt that there should be a

greater interest in the problem of human excellence

and political virtue. Through his writings, Strauss

constantly raised the question of how, and to what

extent, freedom and excellence can coexist. Strauss

refused to make do with any simplistic or one - sided

resolutions of the Socratic question: What

is the good for the

city and man?

Two significant political - philosophical dialogues Strauss had with living thinkers were those he held with Carl Schmitt and Alexandre Kojève. Schmitt, who would later become, for a short time, the chief jurist of Nazi Germany, was one of the first important German academics to positively review Strauss's early work. Schmitt's positive reference for, and approval of, Strauss's work on Hobbes was instrumental in winning Strauss the scholarship funding that allowed him to leave Germany. Strauss's critique and clarifications of The Concept of the Political led Schmitt to make significant emendations in its second edition. Writing to Schmitt in 1932, Strauss summarised Schmitt's political theology thus: "[B]ecause man is by nature evil, he therefore needs dominion. But dominion can be established, that is, men can be unified only in a unity against - against other men. Every association of men is necessarily a separation from other men... the political thus understood is not the constitutive principle of the state, of order, but a condition of the state." Strauss, however, directly opposed Schmitt's position. For Strauss, Schmitt and his return to Hobbes helpfully clarified the nature of our political existence and our modern self - understanding. Schmitt's position is therefore symptomatic of the modern liberal self - understanding. Strauss believed that such an analysis, as in Hobbes' time, served as a useful "preparatory action", revealing our contemporary orientation towards the eternal problems of politics (social existence). But for Strauss, Schmitt's reification of our modern self - understanding of the problem of politics into a political theology was not an adequate solution. Strauss instead advocated a return to a broader classical understanding of human nature, and a tentative return to political philosophy, in the tradition of the ancient philosophers.

With Alexandre Kojève, Strauss had a

close and lifelong philosophical friendship. They had

first met as students in Berlin. The two thinkers

shared a boundless philosophical respect for each

other. Kojève would later write that, without

befriending Strauss, "I never would have known [...]

what philosophy is." The political

- philosophical dispute between Kojève and

Strauss centred on the role that philosophy should and

can be allowed to play in politics. Kojève, who

as a senior statesman in the French government was

instrumental in the creation of the EU, argued that philosophers should

have an active role in shaping political events.

Strauss, on the contrary, believed that philosophy and

political conditions were fundamentally opposed, and

believed that philosophers should not, and must not,

have a role in politics, noting the disastrous results

of Plato in Syracuse. Strauss believed that

philosophers should play a role in politics only to

the extent that they can ensure that philosophy, which

he saw as mankind's highest activity, can be free from

political intervention.

Strauss taught that liberalism in

its modern form contained within it an intrinsic

tendency towards extreme relativism, which in turn led to

two types of nihilism. The

first was a “brutal” nihilism, expressed in Nazi and Marxist regimes.

In On

Tyranny, he wrote that these ideologies,

both descendants of Enlightenment thought,

tried to destroy all traditions, history, ethics,

and moral standards and replace them by force

under which nature and mankind are subjugated and

conquered. The

second type – the "gentle" nihilism expressed in

Western liberal democracies – was

a kind of value - free aimlessness and a hedonistic "permissive egalitarianism", which he saw as

permeating the fabric of contemporary American

society. In

the belief that 20th century relativism, scientism, historicism, and nihilism were all

implicated in the deterioration of modern society and

philosophy, Strauss sought to uncover the

philosophical pathways that had led to this

situation. The resultant study led him to advocate

a tentative return to classical political

philosophy as a starting point for judging

political action.

According to Strauss, Karl Popper's The Open Society and

Its Enemies had

mistaken the city - in - speech described in

Plato's Republic for a

blueprint for regime reform. Strauss quotes Cicero, "The Republic does

not bring to light the best possible regime but

rather the nature of political things – the nature

of the city." Strauss

argued that the city - in - speech was unnatural,

precisely because "it is rendered possible by the

abstraction from eros". The city

- in - speech abstracted from eros, or

bodily needs, and therefore could never guide

politics in the manner Popper claimed. Though

skeptical of "progress", Strauss was equally

skeptical about political agendas of "return"

(which is the term he used in contrast to

progress). In fact, he was consistently suspicious

of anything claiming to be a solution to an old

political or philosophical problem. He spoke of

the danger in trying to finally resolve the debate

between rationalism and traditionalism in

politics. In particular, along with many in the

pre - World War II German

Right, he feared people trying to force a world state to

come into being in the future, thinking that it

would inevitably become a tyranny.

Strauss constantly stressed the importance of two dichotomies in political philosophy: Athens and Jerusalem (Reason and Revelation) and Ancient versus Modern. The "Ancients" were the Socratic philosophers and their intellectual heirs, and the "Moderns" start with Niccolò Machiavelli. The contrast between Ancients and Moderns was understood to be related to the unresolvable tension between Reason and Revelation. The Socratics, reacting to the first Greek philosophers, brought philosophy back to earth, and hence back to the marketplace, making it more political.

The Moderns reacted to the dominance of

revelation in medieval society

by promoting the possibilities of Reason very

strongly. They objected the merger of natural right

and natural theology proposed

by Thomas Aquinas which

resulted in the vulnerability of natural right to

theological disputes along with Aquinas' moral

rigidity highlighted by the prohibition of divorce and birth control. Thomas Hobbes, under the influence of Francis Bacon, re-oriented political

thought to what was most solid but most low in man,

setting a precedent for John Locke and the later

economic approach to political thought, such as,

initially, in David Hume and Adam Smith.

As a youth, Strauss was a political Zionist, belonging to the German Zionist youth group, along with friends Gershom Scholem and Walter Benjamin, who were both strong admirers of Strauss, and would continue to be so throughout their lives. When he was 17, as he said, he was "converted" to political Zionism as a follower of Vladimir Jabotinsky. He served several years in the activities of the German Zionist youth movement, writing several essays pertaining to its controversies, but had left these activities behind by his early twenties.

While Strauss maintained a sympathy and interest in Zionism, he later came to refer to Zionism as "problematic" and became disillusioned with some of its aims.

He taught at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for 1954 – 55 academic year. In his letter to a National Review editor, Strauss asked why Israel is called a racist state in an article in that journal. He argues that the author did not provide enough proof for his argument. He ends up his essay with the following statement:

Political Zionism is problematic for obvious reasons. But I can never forget what it achieved as a moral force in an era of complete dissolution. It helped to stem the tide of "progressive" leveling of venerable, ancestral differences; it fulfilled a conservative function.

Although Strauss espoused the utility of religious belief, there is some question about his views on its truth. In some quarters the opinion has been that, whatever his views on the utility of religion, he was personally an atheist. Strauss, however, was openly disdainful of atheism, as he made apparent in his writings on Max Weber. He especially disapproved of contemporary dogmatic disbelief, which he considered intemperate and irrational and felt that one should either be "the philosopher open to the challenge of theology or the theologian open to the challenge of philosophy." One interpretation is that Strauss, in the interplay of Jerusalem and Athens, or revelation and reason, sought, as did Thomas Aquinas, to hold revelation to the rigours of reason, but where Aquinas saw an amicable interplay, Strauss saw two impregnable fortresses. Werner Dannhauser, in analyzing Strauss' letters, writes, "It will not do to simply think of Strauss as a godless, a secular, a lukewarm Jew." As one commenter put it:

Strauss was not himself an orthodox believer, neither was he a convinced atheist. Since whether or not to accept a purported divine revelation is itself one of the “permanent” questions, orthodoxy must always remain an option equally as defensible as unbelief.

Feser's statement, quoted above, invites the suspicion that Strauss may have been an un-convinced atheist, or that he welcomed religion as merely (practically) useful, rather than as true. The supposition that Strauss was an unconvinced atheist is not necessarily incompatible with Dannhauser's tentative claim that Strauss was an atheist behind closed doors. Hilail Gildin responded to Dannhauser's reading in "Déjà Jew All Over Again: Dannhauser on Leo Strauss and Atheism," an article published in Interpretation: A Journal of Political Philosophy. Gildin exposed inconsistencies between Strauss's writings and Dannhauser's claims; Gildin also questioned the inherent consistency of Dannhauser's admittedly tentative evaluation of Strauss's understanding of divinity and religion.

At the end of his The

City and Man, Strauss invites his reader

to "be open to the full impact of the all -

important question which is coeval with

philosophy although the philosophers do not

frequently pronounce it - -the question quid

sit deus". As a philosopher, Strauss would

be interested in knowing the nature of divinity,

instead of trying to dispute the very being of

divinity. But Strauss did not remain "neutral"

to the question about the "quid" of divinity.

Already in his Natural

Right and History, he defended a Socratic

(Platonic, Ciceronian, and Aristotelian) reading

of divinity, distinguishing it from a

materialistic / conventionalist or Epicurean

reading. Here, the question of "religion" (what

is religion?) is inseparable from the question

of the nature of civil society, and thus of

civil right, or right having authoritative

representation, or right capable of defending

itself (Latin: Jus).

Atheism, whether convinced (overt) or

unconvinced (tacit), is integral to the

conventionalist reading of civil authority, and

thereby of religion in its originally civil

valence, a reading against which Strauss argues

throughout his volume. Thus Strauss's own

arguments contradict the thesis imputed to him

post mortem by scholars such as S. Drury who

profess that Strauss approached religion as an

instrument devoid of inherent purpose or

meaning.

Critics of Strauss accuse him of being elitist, illiberalist and anti - democratic. Shadia Drury, in Leo Strauss and the American Right (1999), argues that Strauss inculcated an elitist strain in American political leaders linked to imperialist militarism, neoconservatism and Christian fundamentalism. Drury argues that Strauss teaches that "perpetual deception of the citizens by those in power is critical because they need to be led, and they need strong rulers to tell them what's good for them." Nicholas Xenos similarly argues that Strauss was "an anti - democrat in a fundamental sense, a true reactionary. According to Xenos, "Strauss was somebody who wanted to go back to a previous, pre - liberal, pre - bourgeois era of blood and guts, of imperial domination, of authoritarian rule, of pure fascism."

Strauss has also been criticized by some conservatives. According to Claes Ryn, the "new Jacobinism" of the "neoconservative" philosophy, a philosophy that Ryn controversially attributes to Strauss, is not "new, it is the rhetoric of Saint - Just and Trotsky that the philosophically impoverished American Right has taken over with mindless alacrity. Republican operators and think tanks apparently believe they can carry the electorate by appealing to yesterday’s leftist clichés.

Noam Chomsky has argued that Strauss's theory is a form of Leninism, in which society should be led by a group of elite vanguards, whose job is to protect liberal society against the dangers of excessive individualism, and creating inspiring myths to make the masses believe that they are fighting against anti - democratic and anti - liberal forces.

Journalists, such as Seymour Hersh,

have opined that Strauss endorsed noble lies,

"myths used by political leaders seeking to

maintain a cohesive society". In The City and Man, Strauss

discusses the myths outlined in Plato's Republic that

are required for all governments. These include

a belief that the state's land belongs to it

even though it was likely acquired

illegitimately and that citizenship is rooted in

something more than the accidents of birth.

In his 2009 book, Straussophobia, Peter Minowitz provides a detailed critique of Drury, Xenos, and other critics of Strauss whom he accuses of “bigotry and buffoonery.” In his 2006 book review of Reading Leo Strauss, by Steven B. Smith, Robert Alter writes that Smith "persuasively sets the record straight on Strauss's political views and on what his writing is really about." Smith refutes the link between Strauss and neoconservative thought (a link that some commentators have controversially made), arguing that Strauss was never personally active in politics, never endorsed imperialism, and questioned the utility of political philosophy for the practice of politics. In particular, Strauss argued that Plato's myth of the Philosopher king should be read as a reductio ad absurdum, and that philosophers should understand politics, not in order to influence policy, except insofar as they can ensure philosophy's autonomy from politics. Additionally, Mark Lilla has argued that the attribution to Strauss of neoconservative views contradicts a careful reading of Strauss' actual texts, in particular On Tyranny. Lilla summarizes Strauss as follows:

Philosophy must always be aware of the dangers of tyranny, as a threat to both political decency and the philosophical life. It must understand enough about politics to defend its own autonomy, without falling into the error of thinking that philosophy can shape the political world according to its own lights.

Finally, responding to

charges that Strauss's teachings fostered the

neoconservative foreign policy of the George W.

Bush administration, such as "unrealistic hopes

for the spread of liberal democracy through

military conquest," Professor Nathan Tarcov,

Director of the Leo Strauss Center at the

University of Chicago, in an article published

in The

American Interest asserts

that Strauss as a political philosopher was

essentially non - political. After an exegesis

of the very limited practical political views to

be gleaned from Strauss's writings, Tarcov

concludes that "Strauss can remind us of the

permanent problems, but we have only ourselves

to blame for our faulty solutions to the

problems of today." Likewise

Strauss's daughter, Jenny Strauss Clay, in a New

York Times article

defended her father against the charge that he

was the "mastermind behind the neoconservative

ideologues who control United States foreign

policy." "He was a conservative," she says,

"insofar as he did not think change is

necessarily change for the better." Since

contemporary academia "leaned to the left" with

its "unquestioned faith in progress and science

combined with a queasiness regarding any kind of

moral judgment," Strauss questioned the tenets

of the left. Had academia leaned to the right

he'd have questioned — and did question — the

tenets of the right as well. In sum,

to the charge of fostering political ideology,

whether of the Bush administration or any other,

Strauss would plead not guilty — according to

him the perennial problem remains whether those

already ill - disposed could give political

philosophy a fair hearing.

Notable people

who studied under Strauss, or attended his

lecture courses at the University of

Chicago, include Hadley Arkes, Seth Benardete, Allan Bloom,

Werner Dannhauser, Murray Dry, William Galston, Victor Gourevitch, Harry V. Jaffa, Roger Masters, Thomas Pangle, Stanley Rosen, Abram Shulsky (Director

of the Office of Special

Plans), and Paul Wolfowitz (who attended two

lecture courses by Strauss on Plato

and Montesquieu's Spirit

of the Laws at

the University of

Chicago). Harvey C.

Mansfield, though never a student

of Strauss, is a noted "Straussian" (as some

followers of Strauss identify themselves). Richard Rorty described

Strauss as a particular influence in his

early studies at the University of Chicago,

where Rorty studied a "classical curriculum"

under Strauss.