<Back to Index>

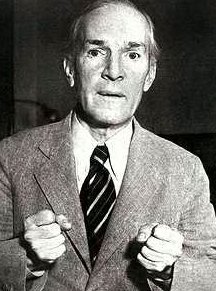

- Political Philosopher Leo Strauss, 1899

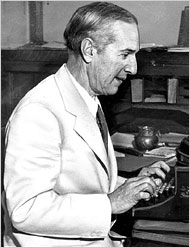

- Writer Upton Beall Sinclair Jr., 1878

- Explorer and Colonial Administrator Maurice Benyovszky, 1746

PAGE SPONSOR

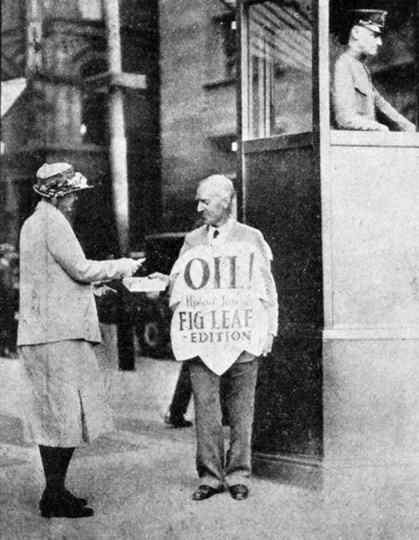

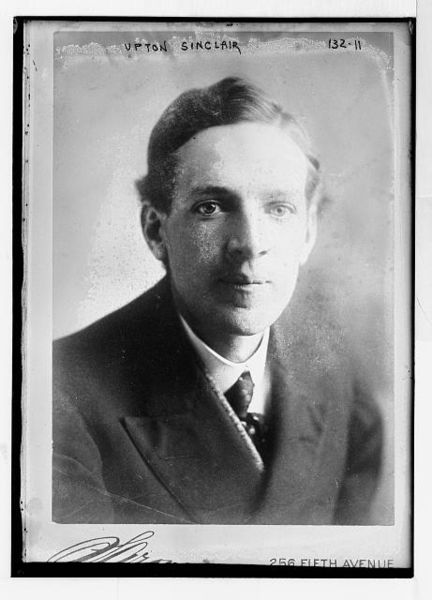

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968), was an American author who wrote close to 100 books in many genres. He achieved popularity in the first half of the 20th century, acquiring particular fame for his 1906 muckraking novel The Jungle. It exposed conditions in the U.S. meat packing industry, causing a public uproar that contributed in part to the passage a few months later of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act. Time magazine called him "a man with every gift except humor and silence."

Sinclair was born in Baltimore, Maryland to Upton Beall Sinclair and Priscilla Harden. His father was a liquor salesman whose alcoholism shadowed his son's childhood. Sinclair had wealthy grandparents with whom he often stayed. This gave him insight into how both the rich and the poor lived during the late 19th century. Living in two social settings affected him and greatly influenced his novels.

In 1888, the Sinclair family moved to the Bronx, New York, where Sinclair

entered the City College of New York, then a prep

school, at the age of thirteen. He wrote dime novels and

magazine articles to pay for his tuition. He graduated

in 1897 and then studied for a time at Columbia University.

In 1904 Sinclair spent seven weeks in disguise, working undercover in Chicago's meatpacking plants to research his fictional exposé, The Jungle. When it appeared in 1906, it became a bestseller. With the income from The Jungle, Sinclair founded the utopian Helicon Home Colony in Englewood, New Jersey. He ran as a Socialist candidate for Congress. The colony burned down under suspicious circumstances within a year.

During his years with his second wife, Mary Craig (or Craig, as she is called in references), Sinclair wrote or produced several films. Recruited by Charlie Chaplin, Sinclair and Mary Craig produced Eisenstein's ¡Qué viva México! in 1930 - 32.

The Sinclairs moved to California in the

1920s and lived there for nearly four decades. Late in

life Sinclair, with his third wife, moved to Buckeye, Arizona, and then to Bound Brook, New Jersey. Sinclair died

there in a nursing home on November 25, 1968. He is buried

in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C., next to his third

wife, Mary Willis, who died a year before him.

Aside from his political and social writings, Sinclair took an interest in psychic phenomena and experimented with telepathy. His book entitled Mental Radio was published in 1930 and included accounts of his wife Mary's experiences and ability.

The Upton Sinclair House in Monrovia, California, is now a National Historic Landmark. The

papers, photographs, and first editions of most of

Sinclair's books are found at the Lilly Library at Indiana University in Bloomington.

In the 1920s the Sinclairs moved to Monrovia, California, near Los Angeles, where Upton founded the state's chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Wanting to pursue politics, he twice ran unsuccessfully for Congress on the Socialist ticket: in 1920 for the House of Representatives and in 1922 for the Senate. During this period, Sinclair was also active in radical politics in Los Angeles. For instance, in 1923, to support the challenged free speech rights of Industrial Workers of the World, Sinclair spoke at a rally in San Pedro, California, in a neighborhood now known as Liberty Hill. He began to read from the Bill of Rights and was promptly arrested, along with hundreds of others, by the LAPD. The arresting officer proclaimed that "we'll have none of that Constitution stuff."

In 1934 Sinclair ran in the California gubernatorial election as a Democrat. Gaining 879,000 votes made this his most successful run for office, but Frank F. Merriam defeated him by a sizable margin. Sinclair's platform, known as the End Poverty in California movement (EPIC), galvanized the support of the Democratic Party, and Sinclair gained its nomination.

Severe dust storms during the Great Depression made farming on the Great Plains impossible, and hundreds of thousands of Southern and Great Plains residents migrated westward in the 1930s in the hope of finding work and a new life. Sinclair's plan to end poverty quickly became a controversial issue under the pressure of so many migrants. Conservatives considered his proposal an attempted communist takeover of their state and quickly opposed him, using propaganda to portray Sinclair as a staunch communist. At the same time, American and Soviet communists disassociated themselves from him as a capitalist. Science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein was deeply involved in Sinclair's campaign. Heinlein tried to obscure this in later life, as he wanted to keep his personal politics separate from his public image as an author.

After his loss to Merriam, Sinclair abandoned EPIC and politics to return to writing. In 1935 Sinclair published I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked, in which he described the techniques employed by Merriam's supporters, including the popular Aimee Semple McPherson, who vehemently opposed socialism and what she perceived as Sinclair's modernism.

Of his gubernatorial bid, Sinclair remarked in 1951:

"The American People will take Socialism, but they won't take the label. I certainly proved it in the case of EPIC. Running on the Socialist ticket I got 60,000 votes, and running on the slogan to 'End Poverty in California' I got 879,000. I think we simply have to recognize the fact that our enemies have succeeded in spreading the Big Lie. There is no use attacking it by a front attack, it is much better to out - flank them."

Sinclair married his first wife, Meta Fuller, in 1902. Around 1911, Meta left Sinclair for the poet Harry Kemp, later known as the Dunes Poet of Provincetown, Massachusetts. In 1913 Sinclair married Mary Craig Kimbrough (1883 – 1961), a woman from an elite Greenwood, Mississippi, family who had written articles and a book on Winnie Davis, the "Daughter of the Confederacy". In the 1920s, they moved to California. They were married until her death in 1961. After Craig's death in 1961, Sinclair married Mary Elizabeth Willis (1882 – 1967).

Sinclair devoted his writing career to documenting and criticizing the social and economic conditions of the early twentieth century in both fiction and non-fiction. He exposed his view of the injustices of capitalism and the overwhelming impact of the poverty. He also edited collections of fiction and non-fiction.

In The Jungle (1906),

Sinclair gave a scathing indictment of unregulated

capitalism as exemplified in the meatpacking

industry. His descriptions of both the unsanitary

conditions and the inhumane conditions experienced

by the workers shocked and galvanized readers.

Sinclair had intended it as an attack upon

capitalist enterprise, but readers reacted

viscerally. Domestic and foreign purchases of

American meat fell by half. Sinclair

lamented: "I aimed at the public's heart, and by

accident I hit it in the stomach." The novel

was so influential that it spurred government

regulation of the industry, as well as the passage

of the Meat Inspection

Act and

the Pure Food and Drug Act.

- Sylvia (1913) was a novel about a Southern girl. In her autobiography, Mary Craig Sinclair said she had written the book based on her own experiences as a girl, and Upton collaborated with her. She asked him to publish it under his name. When it appeared in 1913, the New York Times called it "the best novel Mr. Sinclair has yet written – so much the best that it stands in a class by itself."

- Sylvia's Marriage (1914), Craig and Sinclair collaborated on a sequel, also published by John C. Winston Company under only Sinclair's name.

In his 1962 autobiography, Upton Sinclair

wrote: "[Mary] Craig had written some tales of her

Southern girlhood; and I had stolen them from her for

a novel to be called Sylvia."

Between 1940 and 1953, Sinclair wrote a series of 11 novels featuring a central character named Lanny Budd. He was the son of an American arms manufacturer who moved in the confidence of world leaders, not simply witnessing events but often propelling them. The protagonist has been characterized as the antithesis of the "Ugly American", a sophisticated socialite who mingles easily with people from all cultures and socioeconomic classes.

The series covers in sequence much of the

political history of the Western world, particularly

Europe and America, in the first half of the twentieth

century. Out of print and almost totally forgotten

today, the novels were all bestsellers upon

publication and were published in 21 countries. The

third book in the series, Dragon's Teeth, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1943.

Sinclair is extensively featured in Harry Turtledove's American Empire trilogy, an alternate history series in which the American Socialist Party succeeds in becoming a major force in U.S. politics following two humiliating military defeats to the Confederate States and the post 1882 collapse of the Republican Party, with Abraham Lincoln leading a large number of Republicans into the Socialist Party. He wins the 1920 and 1924 presidential elections and becomes the first Socialist President of the United States, his inauguration attended by crowds of jubilant militants waving red flags. However, the actual policies which Turtledove attributes to him, once in power, are not particularly radical.

In the late 1990s, the television program Working used as its setting a company named Upton Weber. With the show's implicit criticism of contemporary working conditions, however watered down for popular audiences, the name suggests a reference both to Upton Sinclair and Max Weber.

Sinclair

is featured as one of the main characters in Chris Bachelder's satirical fictional

book, U.S.!:

a Novel. Repeatedly, Sinclair is resurrected as

a personification of the contemporary failings of the

American left and portrayed as a quixotic reformer

attempting to stir an apathetic American public to

implement socialism in America.

- The Jungle (1906) was adapted for film in 1914. Sinclair appears at the beginning and end of the film "as a form of endorsement."

- The Wet Parade (1931) became a film directed by Victor Fleming in 1932. It starred Robert Young, Myrna Loy, Walter Huston, and Jimmy Durante.

- The Gnomobile (1937) was the basis of a 1967 Disney musical motion picture, The Gnome - Mobile.

- Oil! (1927) was the basis of There Will Be Blood (2007), starring Daniel Day - Lewis and Paul Dano. It was written, produced, and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. The film received eight Oscar nominations and won two.